Semantics/Lexical Semantics

- Grammar

- Semantics

- Exegetical Issues

- Discourse

- Poetics

- Synthesis

- Close-but-Clear

- Videos

- Post to wiki

Version: 1.0

Overseer: Ian Atkinson

Introduction

Semantics is the study of how language is used to represent meaning. The goal of semantic analysis for interpreting and translating the Bible is to understand the meaning of words and how they relate to each other in context. We want to understand what is implicit about word meaning – and thus assumed by the original audience – and make it explicit – and thus clear for us who are removed by time, language, and culture.

One major branch of semantic study is lexical semantics, which refers to the study of word meanings. It examines semantic range (=possible meanings of a word), the relationship between words (e.g. synonymy, hyponymy), as well as the relationship between words and larger concepts (conceptual domains). One component of our approach involves not only the study of the Hebrew word meaning, but also of our own assumptions about word meaning in modern languages. Because the researcher necessarily starts with their own cultural assumptions (in our case, those of Western-trained scholars), this part of the analysis should be done afresh for every culture.

One of the characteristics of poetry, including its use of words, is its tendency to bend the normal "rules" of language. The Psalms, as biblical poetry, are no exception. They combine words creatively, including rare and archaic terms and those chosen for their phonetic qualities. When there is good evidence to suppose so, the Psalms may also be said to exploit the polysemous potential in language rather than using words according to a single, narrow sense. [1]

Lexical semantics is one of four parts of semantic analysis (cf. verbal semantics, mid-level semantics, and unit-level semantics), which ultimately must be taken together as part of a full interpretation.

Semantic Domains

Semantic domains are split into lexical domains and contextual domains. A lexical domain represents a cognitive category (i.e. a basic category of thought). For example, the word rice is part of the lexical domain of “cereal/grain” (along with the words millet, barley, and wheat). The lexical domain to which a word belongs differs from culture to culture.

A contextual domain, on the other hand, represents a cognitive frame which includes words associated because they tend to occur together in that frame. Think of this as a scene with a setting, props and participants. For a farmer, the contextual domain of the word rice might be “cultivation.” Words within the contextual domain are not limited to a certain part of speech, but can include nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc. In this case, terms that make up the mental image associated with the contextual domain "cultivation" might include not only rice, but field, plowing, harvest.

A gloss is a word used to translate a term in a given context. However, it will usually only be appropriate in some contexts and can be misleading if confused with a fuller definition. Glosses can be helpful tools, but should be used with care.

Semantic Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew

The Semantic Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew (SDBH) approaches word meaning from the perspective of cognitive linguistics and, in particular, semantic domain theory. You can watch an introduction to SDBH here (video)

SDBH provides a table which shows the semantic domains of each word of a given psalm. In addition to the verse number, lemma, and part of speech, each entry includes the following:

- lexical domains in bright green (Praise)

- contextual domains in purple (Joy and Grief)

- definitions in black (state of being considered fortunate and blessed by God)

- glosses in teal/brown (happiness; blessedness)

You can access the SDBH page for a given psalm here (substituting the relevant chapter for the final “1”): https://semanticdictionary.org/overview.php?book=19&chapter=1.

Required Tools

- Open-source Hebrew text

- OSHB Read

- This is what you will use for any Hebrew text that needs to be copy/pasted.

- Grammatical diagram

- This is the same grammatical diagram that you completed in the previous layer.

- Lexicons

- In addition to SDBH (#1 below), the major Hebrew dictionaries are as follows

- SDBH

- Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT) (available on "Translator's Workplace")

- Brown–Driver–Briggs (BDB)

- Dictionary of Classical Hebrew (available on "Translator's Workplace")

- Versions

- Ancient Versions

- Modern Versions

- Additional Information

- Versions with asterisks are required. Versions without asterisks are recommended but not required.

- To see all of these translations linked to a specific psalm, visit the wiki page "Psalm # Translations" (e.g., Psalm 8 Translations).

Steps

1. Complete initial lexical study.

A. Provide English glosses.

On the grammatical diagram, supply English glosses for each Hebrew word or phrase. Provide the same gloss for repeated Hebrew roots/lexemes (when possible). Use the glosses provided in SDBH. If an alternate diagram is provided, gloss those words too. Follow these formatting conventions:

– Preferred diagram glosses: blue (#2D9BF0), bolded.

– Supplied information: Gray (#808080), bolded.

– Alternative diagram glosses: Pink (#FFC3C3), bolded.

– Center English glosses above each Hebrew word. If there is no space, place alongside.

As you work, you may find it useful to research difficult words or common words whose meaning in a given passage is not clear. At times, this may require additional concordance work, careful attention to the ancient versions and interactions with secondary literature. If, after this process, you decide from SDBH, you should explain your reasoning and post your comment to the forum as SDBH feedback, tagging @rdeblois. Also leave a text box that contains your findings on the Miro board beside the lexeme. The note may simply serve as a repository for your thoughts. For each note it is good practice to title it in bold and discuss the various options as cite sources accordingly.

If a difficult word is either poorly attested or not attested at all in the Hebrew Bible, you may either need to look up cognates in other Semitic Languages or check any cognates suggested in secondary literature. Cognates are pairs of words in different languages that were once a single word in an older ancestor of those languages. A native English speaker can immediately tell that English ‘Apple’ and German ‘Apfel’ are related. They descend from the word for ‘apple’ in an older language (proto-West Germanic *appl-) from which German and English themselves descend. English ‘Apple’ and German ‘Apfel’ would therefore be cognates.

Extra care must be taken when looking for cognates in Semitic languages. Two consonants from the proto-language may have merged, or one consonant may have split. Always consult the chart provided to the right (‘Semitic Consonants Correspondences’) in order to see which consonants correspond to each other. For example, looking up the Arabic cognate for the Hebrew root שׁל׳׳ג (lexical class of ‘snowing’) under the letter shin (ش) in the Arabic dictionary will prove to be a fruitless endeavour. It is only after consulting the correspondences that one sees Hebrew shin (שׁ) corresponds to Arabic thaʾ (ث). When one now turns to the entries under thaʾ (ث) in the Arabic dictionary, they are happy to find the Arabic root th-l-g (lexical class of ‘snowing’). The correspondences work 95% of the time, so violate them at your peril.

When figurative language is in play at the word level (rather than the phrase level), include both the literal and the figurative language, separating them by a double arrow ('>>'). Put in bold the wording you are recommending for the CBC. When the literal language works well in English, you may be preserve that, but you need to ALSO include the figurative language for the sake of fullness and in anticipation of localising into other languages.

Use the same mechanism for language that needs to be changed in any way, even if not because it is figurative.

Gloss verbs either as bare infinitives (e.g. 'smash') or with tense/mood/aspect ('may he smash') as you see fit. These will be updated regularly, to be finalised after Verbal Semantics. By then, all verb glosses will be fully inflected.

Note: for pronominal suffixes which are represented in construct with a noun, provide the gloss in the accusative case, e.g. him (not "his"), us (not "our").

Note: for grammatical particles such as the definite direct object marker (אֵת) or the imperative particle (נָא), indicate these using the same font colour and size as the glosses; however instead of bold font, use italics within square brackets.

B. Write a lexical semantics paraphrase.

Provide a paraphrase for each verse. You may either write each verse's paraphrase after providing glosses for that verse or wait until you have glossed each word in the Psalm. The paraphrase should consist of fluid, natural English (i.e. not wooden, word-for-word from the Hebrew). Focus on conveying the sense of each word as used in the current context, and elaborate as needed. The diagram gloss may or may not be the most appropriate word choice for the paraphrase. You may use parentheses or restatement if helpful, but be judicious. As the meanings are clarified, patterns of coherence will emerge. The ultimate purpose of the paraphrase is to discover, as early as possible, these patterns of coherence. Exercise freedom to depart from default glosses (e.g. for אהב, usually glossed "to love," a better rendering in context may be "to be dedicated to").

If your text has an important alternate reading (e.g. a textual variant, alternative construal of the grammar, etc.), then represent this in your paraphrase using pink font. These should be limited to alternatives that are represented by the versions (ancient or modern) and that have exegetical impact.

Note: this paraphrase is not an official translation, and it will not be published. It is intended to be a lexical semantics tool for creators and reviewers. It has proven immensely valuable for non-guardians to be oriented quickly to how a guardian is understanding a psalm.

2. Analyse semantic domains.

A. Identify repeated and/or key lexical and contextual domains.

Using the SDBH page for your psalm, take note of which lexical and contextual domains recur most often or are located in critical places. This is most easily accomplished by using your computer's search function (CMD + F on Mac, CTRL + F on PC) on the SDBH webpage for your psalm. Depending on the length of your psalm, 3–5 occurrences of the domain is the minimum number of repetitions for it to be noteworthy. In the example provided to the right (‘Lexical domain ‘names’ in Psalm 68’), the lexical domain of ‘names’ occurs 38 times in Psalm 68, obviously a noteworthy domain.

B. Record your observations.

Using a text box, record your observations regarding the significance of the key semantic domains. Ideally, this would consist of a brief summary paragraph—much easier with shorter psalms. For longer and more complex psalms, you may find it more beneficial to list out your data in bullet points, bolding the noteworthy domains (see ‘Lexical Domains in Psalm 68’).

C. Write a mini-story for lexical domains.

Summarise the message of the psalm through the lens of the lexical domains, which means grouping all near-synonyms together so they are understood as reflecting the same domain (e.g. nation, people & community may all become 'groups of people'). Generally the more times a lexical domain is repeated, the larger the font size for that word in the mini-story.

This is NOT a summary of the entire psalm, but only of those elements that are highlighted by the repeated lexical domains. Use colours as best bring out the message of the mini-story.

Further to the previous point, keep the size of this manageable—no more than 8–10 sentences. If your Psalm consists of 16 verses and your mini-story is 10 sentences long, it is no longer a mini-story. This means that—if you have large number of repeated domains—not every single noteworthy domain has to make an appearance in the mini-story, just those essential to the message.

For example, rather than try to fit every sub-domain of ‘Proper name’ in the mini-story of Psalm 68, one may simply mention the name most significant for the psalm (‘Yah’) as a way of consolidation (see ‘Lexical Domain Mini-story from Psalm 68’ to the right).

D. Write a mini-story for contextual domains.

Summarise the message of the psalm through the lens of the contextual domains, which means using vocabulary to draw out connections so they are understood as reflecting the relevant contextual domain (e.g. justice vs righteousness or salvation vs rescue). Use colours as best bring out the message of the mini-story.

The previous comments about length apply here as well.

3. Create Venn diagrams.

A. Select terms for closer study.

Choose at least two words from your psalm that require particular attention. These may be difficult terms, key terms, or simply words that recur several times in the psalm. You may find it helpful to check this list of Old Testament Key Terms. Before proceeding, ensure that a Venn diagram isn't already available for any of your terms. Check the word bank here.

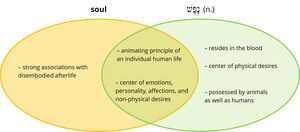

B. Prepare Venn diagram.

Using the Venn diagram template (available on the Miro "templates" board), place the chosen Hebrew word above the right oval and one English gloss above the left oval. For Hebrew verbs, provide the root without vowels and the binyan ("vb. [binyan abbreviation]"); see abbreviations below. For English verb glosses, provide the infinitive form (e.g. to discipline). For other Hebrew words, provide vowels and indicate the part of speech (abbreviated in parentheses).

Abbreviations

Parts of speech

- noun (n.)

- verb (vb.)

- adjective (adj.)

Binyanim

- qal (qal)

- niphal (ni.)

- piel (pi.)

- pual (pu.)

- hiphil (hi.)

- hophal (ho.)

C. Complete Hebrew side.

Using the lexicons listed in "required tools" (including both definitions and semantic domains) provide the definition, definition excerpt, or association of the word (making sure to cite the source).[2] If there are synonym(s) or antonym(s), you may include those at the bottom of the oval. The goal is not to be exhaustive, but to provide several items that help fill out the semantic range of the term in question.

Create a Miro frame and title it using simplified SBL transliteration (e.g. Nefesh). You may find it helpful to use this automatic Hebrew transliteration tool, selecting "SBL General" style.

D. Complete English (or other modern language) side.

Fill in the English gloss oval, consulting at least one English dictionary (e.g. Concise Oxford English Dictionary or Merriam-Webster). You may re-word a definition (as necessary) in order to be most easily compared with the Hebrew definition. As with the Hebrew, you may include synonyms and antonyms at the bottom.

Where the definitions (and associations) are similar to the Hebrew, indicate this by putting them in the overlapping area of the diagram.

Note 1: You may choose to do a second Venn diagram for a given Hebrew word, using a different English gloss. Note 2: Avoid cognates in definitions (e.g. a ‘fool’ is one who acts a‘foolishly’) unless the cognate is more readily intelligible to the audience. Note 3: You are encouraged to write a brief paragraph summarising the Venn, including preliminary translation suggestions.

4. Identify repeated roots.

A. Identify.

Using the template table (available on the Miro "templates" board), identify the roots which are repeated in the psalm and list in order of occurrence. The table should include verse numbers (listed as one row per clause) on the left and the root letters of each word at the top.

Note: the repeated roots table is intended to identify content words (i.e. those that have semantic content, as opposed to function words like prepositions or conjunctions). However, if you find a remarkable repeated function word, then you may include it on the chart too.

Note: this app (by Jason Sommerlad, a friend of the project) has a setting for repeated roots. Enter your chapter number at the top, then choose "Rep" from the sliding menu above the text. The repeated roots will highlight in unique colours. This tool is not intended to replace going through the Psalm by hand since, occasionally, verses from the psalm are missing.

B. Find patterns.

Create a duplicate of the repeated roots table, and look for groupings or breaks.

Is there is a “mid-point” that acts as a line of symmetry, either for the entire psalm or for a section of the psalm? If so, draw this line, and indicate where the roots occur using this colour scheme: roots occurring only in first half (green circle); roots occurring only in second half (blue circle); and roots occurring in both halves (black circle). Include a legend (copied from the Templates board).

Does there appear to be another organising principle within the psalm's repeated roots? Are they functioning in another way? If so, then indicate this where possible. If nothing jumps out, then just leave this table blank for now.

C. Write a repeated roots "mini-story."

Summarise the message of the psalm, through the lens of the repeated roots. You want to capture the effect of the repeated roots. This mini-story is not intended to include everything. Its purpose is simply to illuminate the repeated roots. Generally the more times a root is repeated, the larger the font size for that word in the mini-story. There are two things to capture:

- Roots repeated throughout the entire Psalm (framing the message)

- Roots repeated only in one part or another (often revealing thematic shifts)

Additional Resources

Archer, Gleason L. Jr., Robert Harris, and Bruce K. Waltke, eds. Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Moody Press, 1980 (Logos version, 2002).

The Semantics of Ancient Hebrew Database project

Semantic Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew, edited by Reinier de Blois, with the assistance of Enio R. Mueller, ©2000-2021 United Bible Societies.

Reinier de Blois, "Towards a new dictionary of Biblical Hebrew based on Semantic Domains."

List of semantic domains, developed by Ron Moe (SIL).

Zotero: Lexical Semantics

Rubric

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Completeness | The page includes every element required by the creator guidelines.

|

| Documentation and Engagement with secondary literature |

|

| Clarity of language |

|

| Formatting/Style |

|

References

- ↑ There is an important distinction between polysemy, homophony, and vagueness. Polysemy refers to multiple meanings of a single word (one entry in the dictionary), whereas homophony (sometimes called lexical ambiguity) refers to different words that are spelled the same way (more than one entry in the dictionary). Vagueness refers to a single word with a nonspecific meaning. For tests to distinguish between polysemy and vagueness, see Geeraerts, Dirk. "Lexical Semantics." In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford: OUP, 2017.

- ↑ Do not include homonyms (i.e. different words spelled the same way), but do account for all of the entries for a particular word. When it's not clear, use the entries provided in SDBH (or, where SDBH is incomplete, other lexicons).