Macrosyntax

- Grammar

- Semantics

- Exegetical Issues

- Discourse

- Poetics

- Synthesis

- Close-but-Clear

- Videos

- Post to wiki

- Style Guide

Version:

Overseer: Ian Atkinson

Introduction

This layer is called ‘macrosyntax’ because it analyzes syntactic features above the sentence level, across larger sections of discourse, in terms of both coordination and subordination. Coordination and subordination are themselves determined grammatically by conjunctions, asyndesis, and discourse markers, as well as information flow, insofar as it is determined by syntax (word order).

Recent decades of linguistic research have shown that the distinction between sentence analysis and text analysis is on a continuum. So, following previous layers, we have the tools to apply grammatical analysis not only to the word or clause level, but also to discourse as a whole. The attention given to grammatical relations at the Grammar level is here applied to syntax at the clause level and beyond. This consists of observations of formal features, the morphosyntax, and the packaging of information flow as informed by coordination/subordination, discourse markers, and clausal word order.

Information packaging includes the communication of given and new/unexpected information presented from a base of known information, i.e., what has already been activated in the minds of the interlocutors throughout a discourse, be that entities or events, as well as guiding the reader concerning the sentence topic and the communicative contribution offered by focus (often overtly marked by pre-verbal constituents – see Appendix A below). Thus, the discourse structure offers an intentional construal and perspective in order to guide the reader’s attention as they process the text as a whole. Authors provide the reader discourse-structuring clues regarding what the current question-under-discussion is (often described as "at-issue" content), what is newsworthy and noteworthy, and indeed, where the discourse is going. Being a cooperative reader of Biblical Hebrew poetry involves paying attention to these clues in order to better grasp the cohesive and coherent message of the text.

In short, the purpose of the layer is to determine the syntactic features in a psalm that contribute to its discourse structure.

Steps

Before you begin...

- Copy the macrosyntax template and paste it onto your MIRO board.

- Copy and paste the English and Hebrew texts in the relevant text boxes.

- For all preferred emended or revocalized Hebrew texts, replace the MT reading in the main text with the emended or revocalized Hebrew with astrisks on either side of the altered Hebrew text (e.g., *מֵחֹשֶׁךְ*). The asterisks should be colored purple if the change is a revocalization and blue if an emendation of the consonantal text. Do not supply accents for the altered Hebrew text. At the bottom of the visualiation, add a note for each emendation or revocalization referring to the primary discussion for each variant (usually a note in the grammar layer or an exegetical issue) and providing the MT for comparison. E.g., ** For the revocalization מֵחֹשֶׁךְ, see grammar note (MT: מַחְשָֽׁךְ).

- Delete verse numbers from the text.

1. Clause Delimitation

- Divide the text into clauses according to the grammatical diagram's clausal divisions.

2. Coordination and Subordination

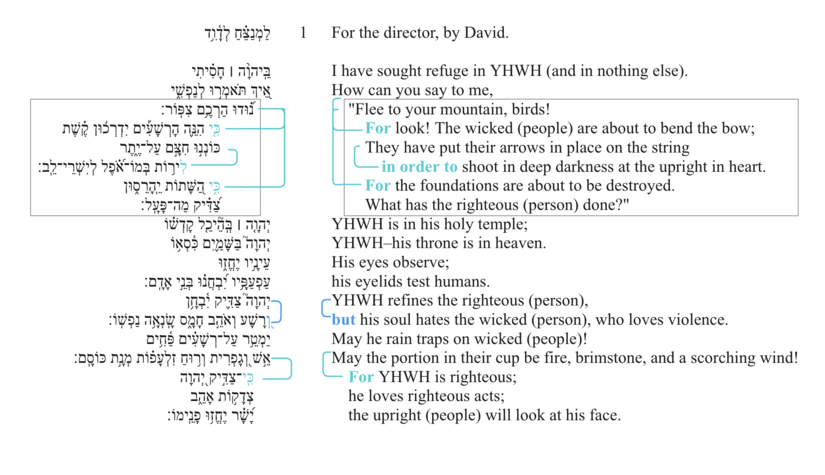

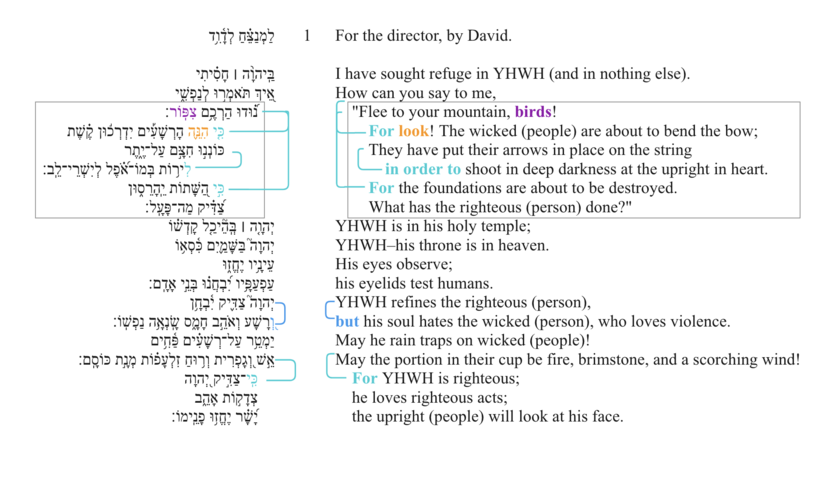

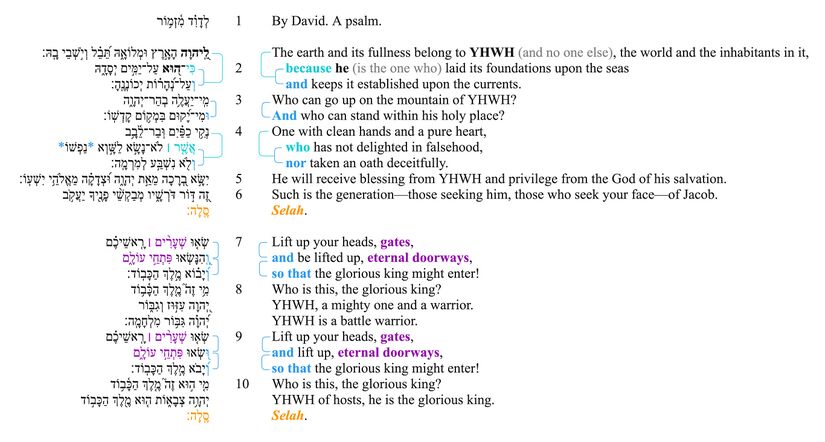

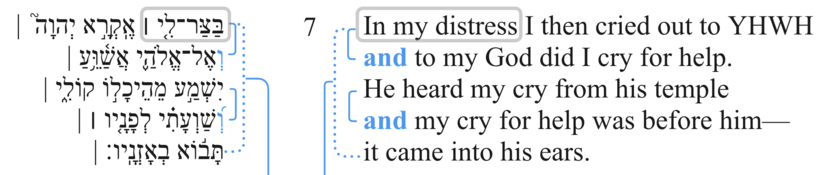

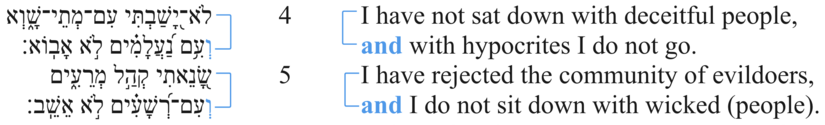

- Color all coordinating conjunctions blue, and use blue lines to connect the clauses which are coordinate (see example below).[1] Bold the coordinating conjunctions in the English text.

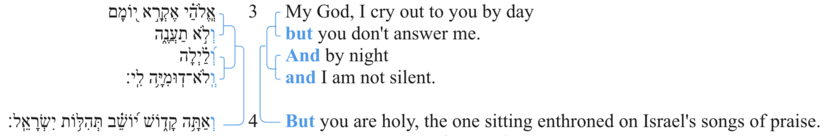

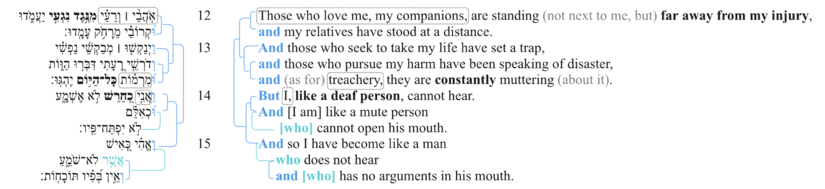

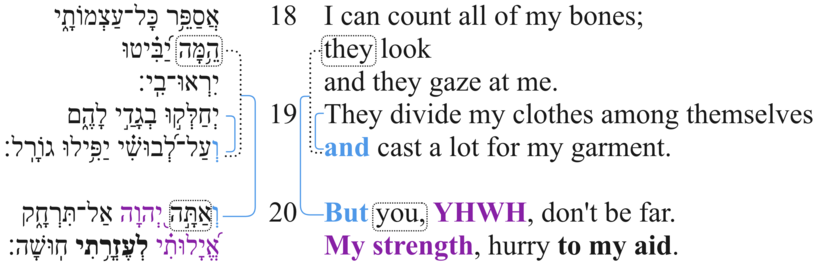

- Where text units bigger than adjacent lines are coordinated, indicate these also with the blue lines and the expanded CBC. Admittedly, this is often semantically derived, but is also often indicated by וַאֲנִי or וְאַתָּה topic shifts or the like (see Pss 22:3-4 and 38:12-15 below). Note that, occasionally this will require revisiting the diagram's treatment of the scope of the waw.

- If such a discourse-level waw is at play and the existing blue curves do not already visualize the scope of coordination, do your best to discern the passage of preceding text that is coordinated by the waw and indicate its scope with a dashed blue curve.

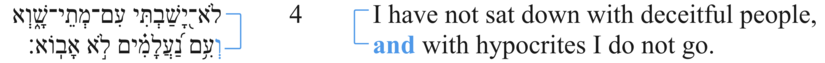

- Color all subordinating elements teal, and use teal lines to connect the clauses which are subordinate. This will include anything diagrammed as subordinate in the grammar layer (e.g., כִּי, relative particles, infinitive constructs that begin with lamed, etc.). Anything colored should also be made bold in the English text.

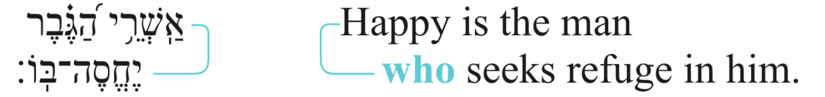

- Use indentation to indicate syntactic subordination. In the case of asyndetic relative clauses, the Hebrew line should be indented as indicated by the asyndetic relationship, and the English gloss of the relative conjunction in teal (for example, Ps. 34:9b):

- Direct speech, introduced by an explicit verb of speech, should be boxed and indented, as any other content clause (whether introduced by כִּי or not).

- Using the notes section of the template, take notes explaining and/or defending any difficult or controversial decisions.

3. Vocatives and Other Discourse Markers

- Color all vocatives purple. Bold the vocatives in the English text. Take notes on the sentence-pragmatic significance of the vocative's position according to the functions discussed in Appendix B.

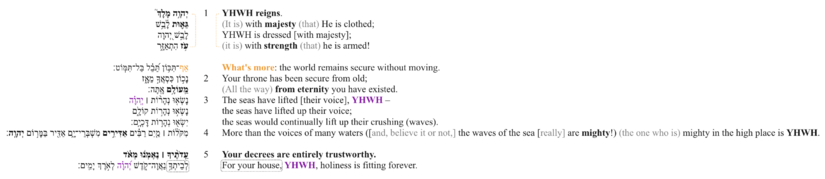

- Color any other discourse markers that might have a text-structuring function orange. These should also be bold in the English text.

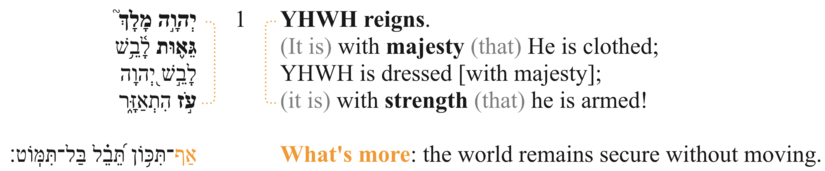

- Try to discern the scope of preceding discourse denoted by the discourse marker and indicate these with dashed orange lines. This will most naturally end up forming the previous discourse unit, as here in Ps 93:1 (see Discourse Unit Delimitation below):

- Selah should be placed on its own line.

4. Word Order

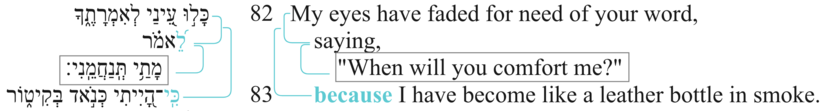

- Note any instances of non-default word order (see Appendix A for possible functions of non-default word order).

- Determine, in each case, the reason for the non-standard word order.

- Provide a dashed box around any instances of marked topic (including left dislocation).[2] Try to discern the scope of the topic's activation, until replaced by another, and indicate this with a dashed curve. (If the topic remains active for as little as one clause, you can omit this detail to not clutter the visual.)

- Provide a solid gray box around any instances of frame setters.[3]

- Bold any instances of marked focus.

- In cases where the word order variation is poetic and not information-structural, do not mark the text. Instead, make a note in the notes section. Where these functions overlap, however, indicate either topic or focus in the CBC as usual.

- Bold any instances of thetic sentences.[4].

- (For explanations and examples of these categories see appendix)

- In the notes section, provide a rationale for each decision and explain its significance.

5. Discourse Unit Delimitation

- On the basis of your observations, divide the text into discourse units using blank lines.

- Readjust any boxes or other figures that become misaligned during the process.

- Add verse numbers in a middle column.

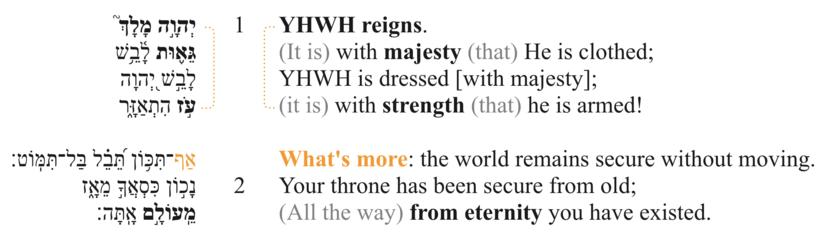

- In the notes section, give a rationale for each division. Be sure that your divisions are based on the elements of macrosyntax you have analyzed up to this point, and not on semantics – whether on the lexical level (e.g., repeated roots) or the discourse level (i.e., the discourse topic ) – verbal semantics (e.g., patterns of verbal forms); participant analysis (e.g., participant shifts) or poetics. In Psalm 93 below, the discontinuities are indicated by the discourse marker אַף between v. 1a and v. 1b, and by the thetic sentence in v. 5.

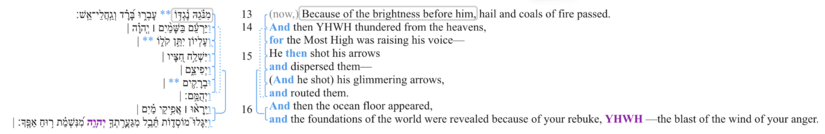

Other examples of discontinuities delimiting larger macrosyntactic units may involve discourse markers (such as the selah in Ps 24:6 and 10 or the כִּי in Ps 91:3, 9 and 14), topic shifting with overt pronouns (such as וְאַתָּה in Ps 22:4 and 20), direct speech (e.g., Ps 68:23-24) or patterns of coordination (e.g., Ps 20) & subordination (e.g., Ps 118:1-4), or distinct predication types, such as exclamatives (e.g., Ps 31:20).

6. Translation Expansion

- Expand the English CBC to highlight the significance of macrosyntactic features. Use gray text and parentheses to mark the expansions.

- E.g., in Ps 93:1 the expansions highlight the focal nature of what the king is clothed and armed with:

Appendices

Appendix A: Non-Default Word Order

Definitions provided in the SIL Linguistics Glossary (adaptations in parenthesis):

A topic is a noun phrase that expresses what a sentence is about, and to which the rest of the sentence is related as a comment.

Focus is a term that refers to information, in a sentence, that

- is (usually) new

- is of high communicative interest

- is marked by (prosodic) stress

- typically occurs late(r) in the sentence (than the topic), and

- complements the presupposed information typically presented early in the sentence.

Note that according to this definition, focal material typically occurs late in the sentence. This would be default word order. So, when it is fronted (placed at the beginning of the clause) we are in the realm of non-default word order.

Because focus depends on what information is already given, context is often required to determine its scope. The scope of focus can be limited to a clausal constituent - subject, object, oblique (constituent focus), or the verb - or it can extend to include the entire predicate (predicate focus). If the entire utterance is new/unexpected it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus").

With V-S-O-(M) being Biblical Hebrew’s default word order, if deviations are caused by information structure, we often have a case of topic shift, reactivating a certain discourse entity, as in :

- רַבִּים֮ אֹמְרִ֪ים לְנַ֫פְשִׁ֥י

- אֵ֤ין יְֽשׁוּעָ֓תָה לּ֬וֹ בֵֽאלֹהִ֬ים סֶֽלָה׃

- וְאַתָּ֣ה יְ֭הוָה מָגֵ֣ן בַּעֲדִ֑י

- (Ps 3:3-4a)

A similar case is found in the וַ֭אֲנִי of Ps 26:11 after discussion of the ‘men of blood’:

- אַל־תֶּאֱסֹ֣ף עִם־חַטָּאִ֣ים נַפְשִׁ֑י

- וְעִם־אַנְשֵׁ֖י דָמִ֣ים חַיָּֽי׃

- אֲשֶׁר־בִּידֵיהֶ֥ם זִמָּ֑ה

- וִֽ֝ימִינָ֗ם מָ֣לְאָה שֹּֽׁחַד׃

- וַ֭אֲנִי בְּתֻמִּ֥י אֵלֵ֗ךְ

- (Ps 26:9-11a)

In this last clause, the modifier בְּתֻמִּ֥י is placed before the verb because it is focused. With ‘I’ being reactivated as topic, the ‘will walk’ is also accessible from the previous discourse (an almost identical phrase is found in v. 1) and the בְּתֻמִּ֥י reaffirms the psalmist’s commitment to how he will walk.

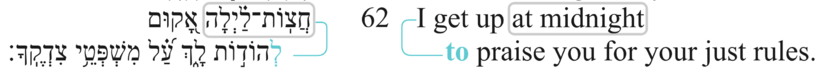

Discourse particles, such as אַף, make clearer the presence of constituent focus (BHRG §47.2):

- אֲבָרֵ֗ךְ אֶת־יְ֭הוָה אֲשֶׁ֣ר יְעָצָ֑נִי

- אַף־לֵ֝יל֗וֹת יִסְּר֥וּנִי כִלְיוֹתָֽי

- (Ps 16:7)

Such constituent focus is at work when answering the question, What did John wash? - He washed the dishes. Who washed the dishes? - John washed them. Less commonly, the verb would be focused in the answer to, What did John do to the dishes? - He washed them.

On the other hand, the default focus structure is predicate focus, as in,

What did John do? - He washed the dishes.

In Ps 16:9, the predicate focus (in this case, equal with verbal focus) exhibits default order in the first two clauses, while in the third clause the subject is fronted as it is focussed, adding another constituent to the body parts mentioned in clauses A and B:

- לָכֵ֤ן ׀ שָׂמַ֣ח לִ֭בִּי

- וַיָּ֣גֶל כְּבוֹדִ֑י

- אַף־בְּ֝שָׂרִ֗י יִשְׁכֹּ֥ן לָבֶֽטַח׃

- (Ps 16:9)

Predicate focus is also found in Ps 26:10b, with the subject fronted in parallel with בִּידֵיהֶ֥ם of the previous clause. ימִינָ֗ם is thus also topically accessible, being primed by the semantic domain of body parts > hands already activated in the previous colon.

- וִֽ֝ימִינָ֗ם מָ֣לְאָה שֹּֽׁחַד

- (Ps 26:10b)

Since the basic focus function is to select a choice among alternatives, imperatives can be viewed as setting the clause up to impose a restricting preference on the choice of action moving forward, while interrogatives prepare possible alternative answers. Imperatives often contain a verbal focus structure, since it is the semantic content of the verb which the addressor wants the addressee to hear and act upon:

- שָׁפְטֵ֤נִי יְהוָ֗ה

- Judge me, YHWH. (Ps. 26:1a)

A thetic construction, however, would be appropriate if John's wife returns home expecting a mess and her kitchen is pristine. To the implicit "What happened?" John could answer: "I cleaned up."

Thetics are clauses not divided between topic and comment; they are thus presented as a unitary state of affairs. As new or unexpected information, they prototypically answer the implicit discourse question under discussion, “What happened?” Thetics prototypically involve bodily sensations, weather terms and verbs of movement, but they can be any state of affairs in which the information is unexpected/new. Prosodic stress may be as follows: ‘Your shoe’s untied’, ‘The computer’s broken’, ‘My head hurts’, ‘It’s raining’, ‘John’s coming’, etc. Often thetics provide the grounds for a neighbouring imperative or interrogative, as in ‘Speak softly! The baby’s sleeping’ and ‘Be careful, the dog bites’.

In this last example, perhaps the hearer is not aware that the speaker even has a dog, but for the sake of conversational cooperation, the hearer can accommodate this culturally acceptable practice of owning a dog as a pet, so that the previous introduction of the dog as a discourse topic is not necessary (as in, ‘Be careful. I have a dog, and it bites’).

Furthermore, it is important to bear in mind that the information will be new/unexpected at this point in the discourse. When telling a joke, we might repeat the punch line, even though its content is no longer new. Or somebody might need to be reminded of an obvious reality: ‘Take it easy, you have a heart condition.’ It is unlikely that the addressee is unaware of his or her heart condition. This repetition for discourse effect is especially prevalent in poetry, which will often blur the simple dichotomy between new and presupposed information.

Besides providing grounds for an imperative/interrogative, thetics also provide thematic pivots (introductions/conclusions) in the discourse, as the following two example:

- רַ֭גְלִי עָֽמְדָ֣ה בְמִישׁ֑וֹר

- (Ps 26:12a)

Sometimes, however, the reading as a thetic construction or a topic-focus construction is not clear. Should the grounding clause, חָסִ֥יתִי בָֽךְ (Ps 16:1), be read as a unitary state of affairs (thetic)? Or should the ‘you’ (ךְ) be read as focal, since it is discourse-presupposed that the psalmist has sought refuge somewhere? Likewise, in יְֽהוָ֗ה מְנָת־חֶלְקִ֥י וְכוֹסִ֑י (Ps 16:5a) is יְֽהוָ֗ה topical with predicate focus? Or is the entire utterance a unified contribution to the information flow? Note any uncertainties in the final ‘Comment’ column, to be discussed with the Layer Overseer and during the review process. As always, all of these discourse conclusions should be confirmed or challenged by work on previous layers.

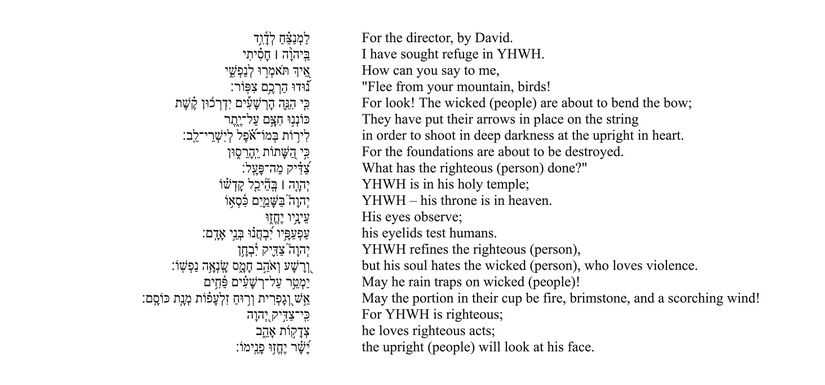

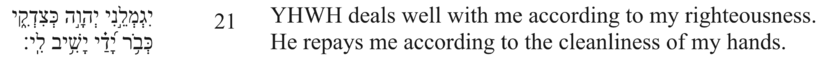

Another purpose of non-default word order, that does not have to do with information flow, is the use of poetic structures to chunk and delimit line groupings. These poetic structure include symmetry (as Pss 11:4; 18:21 and 26:4-5 below), or repetition, or on the constituent level, head-tail linkage and inclusio.

On some occasions, such patterns may function together with a repeated constituent outside the poetic structure, as Ps 44:6:

Though not information-structural, such poetic binding do often contain significant discourse-structuring clues (i.e., indicating discourse continuity or discontinuity), so should be taken into account when making decisions on the discourse unit delimitation.

Appendix B: Vocative Positions

Many of the psalms exhibit vocatives (forms of direct address) in various clause positions. Two models have been proposed in recent years to account for their function. Unfortunately, the literature is slim in this area and one would hope for more comprehensive and linguistically informed treatments in the future. Therefore, consider the following suggested functions as a starting point and apply critically those which reflect the vocative positions found in your Psalm, as it is doubtful that they will accurately reflect all the possible vocative-position functions in the Psalms.

Processing/line delimitation:

- Miller (2010: 360-363) claims that often a vocative assists in delimiting lines phonologically and therefore correctly processing the syntax.

ר֣וּמָה עַל־הַשָּׁמַ֣יִם אֱלֹהִ֑ים עַ֖ל כָּל־הָאָ֣רֶץ כְּבוֹדֶֽךָ׃

Ps 57:6.

וִֽיבֹאֻ֣נִי חֲסָדֶ֣ךָ יְהוָ֑ה תְּ֝שֽׁוּעָתְךָ֗ כְּאִמְרָתֶֽךָ׃

Ps 119:41.

עַד־מָתַ֖י רְשָׁעִ֥ים׀ יְהוָ֑ה עַד־מָ֝תַ֗י רְשָׁעִ֥ים יַעֲלֹֽזוּ׃

Ps 94:3.

אֱלֹהִ֥ים לְהַצִּילֵ֑נִי יְ֝הוָ֗ה לְעֶזְרָ֥תִי חֽוּשָֽׁה׃

Ps 70:2.

Sentence pragmatics:

- If clause-initial (Kim 2022: 213-217), a vocative may (1) signal the beginning of a conversational turn:

וַתִּקֹּ֣ד בַּת־שֶׁ֔בַע וַתִּשְׁתַּ֖חוּ לַמֶּ֑לֶךְ וַיֹּ֥אמֶר הַמֶּ֖לֶךְ מַה־לָּֽךְ׃ וַתֹּ֣אמֶר ל֗וֹ אֲדֹנִי֙ אַתָּ֨ה נִשְׁבַּ֜עְתָּ בַּֽיהוָ֤ה אֱלֹהֶ֙יךָ֙ לַֽאֲמָתֶ֔ךָ כִּֽי־שְׁלֹמֹ֥ה בְנֵ֖ךְ יִמְלֹ֣ךְ אַחֲרָ֑י וְה֖וּא יֵשֵׁ֥ב עַל־כִּסְאִֽי׃

1 Ki 1:16–17.

(2) identify the addressee (perhaps if there are numerous possibilities):

וַֽיִּמְצָאָ֞הּ מַלְאַ֧ךְ יְהוָ֛ה עַל־עֵ֥ין הַמַּ֖יִם בַּמִּדְבָּ֑ר עַל־הָעַ֖יִן בְּדֶ֥רֶךְ שֽׁוּר׃ וַיֹּאמַ֗ר הָגָ֞ר שִׁפְחַ֥ת שָׂרַ֛י אֵֽי־מִזֶּ֥ה בָ֖את וְאָ֣נָה תֵלֵ֑כִי

Ge 16:7–8a.

This is probably the case with the first two vocatives of Ps. 22:24, while the third (24c) exhibits a mirroring structure with 24b:

יִרְאֵ֤י יְהוָ֨ה׀ הַֽלְל֗וּהוּ כָּל־זֶ֣רַע יַעֲקֹ֣ב כַּבְּד֑וּהוּ וְג֥וּרוּ מִ֝מֶּ֗נּוּ כָּל־זֶ֥רַע יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

(3) "grab the attention", i.e. prime the addressee for what follows, often an urgent imperative:

עַתָּה֙ עִם־לְבָבִ֔י לִכְר֣וֹת בְּרִ֔ית לַיהוָ֖ה אֱלֹהֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל וְיָשֹׁ֥ב מִמֶּ֖נּוּ חֲר֥וֹן אַפּֽוֹ׃ בָּנַ֕י עַתָּ֖ה אַל־תִּשָּׁל֑וּ כִּֽי־בָכֶ֞ם בָּחַ֣ר יְהוָ֗ה לַעֲמֹ֤ד לְפָנָיו֙ לְשָׁ֣רְת֔וֹ וְלִהְי֥וֹת ל֖וֹ מְשָׁרְתִ֥ים וּמַקְטִרִֽים׃

2 Ch 29:10–11.

This seems to be the case in Ps. 22:2-3:

אֵלִ֣י אֵ֭לִי לָמָ֣ה עֲזַבְתָּ֑נִי רָח֥וֹק מִֽ֝ישׁוּעָתִ֗י דִּבְרֵ֥י שַׁאֲגָתִֽי׃

אֱֽלֹהַ֗י אֶקְרָ֣א י֖וֹמָם וְלֹ֣א תַעֲנֶ֑ה וְ֝לַ֗יְלָה וְֽלֹא־דֽוּמִיָּ֥ה לִֽי׃

- If the vocative is clause-final, it may be signaling the end of a turn to give the floor to the other interlocutor(s) (Kim 2022: 217-221):

וַיֹּ֨אמֶר יִצְחָ֜ק אֶל־אַבְרָהָ֤ם אָבִיו֙ וַיֹּ֣אמֶר אָבִ֔י וַיֹּ֖אמֶר הִנֶּ֣נִּֽי בְנִ֑י וַיֹּ֗אמֶר הִנֵּ֤ה הָאֵשׁ֙ וְהָ֣עֵצִ֔ים וְאַיֵּ֥ה הַשֶּׂ֖ה לְעֹלָֽה׃ Ge 22:7.

וַ֠יַּעַן הַמַּלְאָ֞ךְ הַדֹּבֵ֥ר בִּי֙ וַיֹּ֣אמֶר אֵלַ֔י הֲל֥וֹא יָדַ֖עְתָּ מָה־הֵ֣מָּה אֵ֑לֶּה וָאֹמַ֖ר לֹ֥א אֲדֹנִֽי׃ וַיַּ֜עַן וַיֹּ֤אמֶר אֵלַי֙

Zec 4:5-6a

- If the vocative is clause-medial, it is generally held to focus the "detached" element. In the case of post-clausal adverb or post-fronted constituent, it may "mark" the detached element as conversationally significant (Kim 2022: 227-233):

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר יוֹאָ֗ב יוֹסֵף֩ יְהוָ֨ה עַל־עַמֹּ֤ו׀ כָּהֵם֙ מֵאָ֣ה פְעָמִ֔ים הֲלֹא֙ אֲדֹנִ֣י הַמֶּ֔לֶךְ כֻּלָּ֥ם לַאדֹנִ֖י לַעֲבָדִ֑ים לָ֣מָּה יְבַקֵּ֥שׁ זֹאת֙ אֲדֹנִ֔י לָ֛מָּה יִהְיֶ֥ה לְאַשְׁמָ֖ה לְיִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

1 Ch 21:3.

וַתֹּ֜אמֶר הָאִשָּׁ֤ה הַתְּקוֹעִית֙ אֶל־הַמֶּ֔לֶךְ עָלַ֞י אֲדֹנִ֥י הַמֶּ֛לֶךְ הֶעָוֺ֖ן וְעַל־בֵּ֣ית אָבִ֑י וְהַמֶּ֥לֶךְ וְכִסְא֖וֹ נָקִֽי׃

2 Sa 14:9.

Miller (2010: 357) claims that if the vocative is the second constituent, the preceding entity is focussed:

כִּֽי־אַתָּה֩ יְהוָ֨ה צְבָא֜וֹת אֱלֹהֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל גָּלִ֜יתָה אֶת־אֹ֤זֶן עַבְדְּךָ֙ לֵאמֹ֔ר בַּ֖יִת אֶבְנֶה־לָּ֑ךְ עַל־כֵּ֗ן מָצָ֤א עַבְדְּךָ֙ אֶת־לִבּ֔וֹ לְהִתְפַּלֵּ֣ל אֵלֶ֔יךָ אֶת־הַתְּפִלָּ֖ה הַזֹּֽאת׃

2 Sa 7:27.

Along similar lines, the pre-vocative and fronted וְאַתָּה in Ps. 22:20 is undoubtedly topical, shifting the discourse from a list of sufferings vv.12-19 to hopeful appeals of help:

וְאַתָּ֣ה יְ֭הוָה אַל־תִּרְחָ֑ק אֱ֝יָלוּתִ֗י לְעֶזְרָ֥תִי חֽוּשָׁה׃

- If the vocative is post-verbal, it may be drawing attention/focussing the following sentence constituent (Kim 2022: 233-235):

הַטֵּ֨ה יְהוָ֤ה׀ אָזְנְךָ֙ וּֽשֲׁמָ֔ע פְּקַ֧ח יְהוָ֛ה עֵינֶ֖יךָ וּרְאֵ֑ה וּשְׁמַ֗ע אֵ֚ת דִּבְרֵ֣י סַנְחֵרִ֔יב אֲשֶׁ֣ר שְׁלָח֔וֹ לְחָרֵ֖ף אֱלֹהִ֥ים חָֽי׃

2 Ki 19:16.

- If the vocative is post-clause-nucleus and preceding only sentence adjuncts, it is "to provide rhetorical highlighting, though of a less specific nature [than focus]" (Miller 2010: 358):

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר ל֗וֹ מַדּ֣וּעַ אַ֠תָּה כָּ֣כָה דַּ֤ל בֶּן־הַמֶּ֙לֶךְ֙ בַּבֹּ֣קֶר בַּבֹּ֔קֶר

2 Sa 13:4a.

- Finally, if the vocative precedes a subordinate clause, it is said to focus the content of the subordinate clause (Kim 2022: 235-237):

וַתֹּ֙אמֶר֙ שְׁבִ֣י בִתִּ֔י עַ֚ד אֲשֶׁ֣ר תֵּֽדְעִ֔ין אֵ֖יךְ יִפֹּ֣ל דָּבָ֑ר כִּ֣י לֹ֤א יִשְׁקֹט֙ הָאִ֔ישׁ כִּֽי־אִם־כִּלָּ֥ה הַדָּבָ֖ר הַיּֽוֹם׃

Ru 3:18.

- Besides these analyses, the function of the clause-medial vocative may be as simple as slowing down the processing of the packaged information and therefore signaling structural significance within the psalm, as is probably the case with Ps. 24:7:

שְׂא֤וּ שְׁעָרִ֨ים׀ רָֽאשֵׁיכֶ֗ם וְֽ֭הִנָּשְׂאוּ פִּתְחֵ֣י עוֹלָ֑ם וְ֝יָב֗וֹא מֶ֣לֶךְ הַכָּבֽוֹד׃

Help

Good Examples

See completed examples here:

Common Mistakes

- Do not indicate any waw–conjoin clause as subordinate, even if semantically subordinate (result, purpose, etc.).

- Do not indicate the presence of topic or focus unless overtly marked by their fronted position. Likewise, verbal focus (or more broadly, predicate focus) is the default, so should not be indicated on the visual, as it is also rarely marked by constituent order in Biblical Hebrew.

- Make sure to provide rationale for the vocative positions based on the suggestions in Appendix B.

- Do not base decisions on discourse discontinuity on any other factors other than the macrosyntactic elements observed in this layer (for example, patterns of verb forms, a new "semantic theme", new participants, etc.).

Additional Resources

Instructional and Sample Videos

Note: the verbal morphology diagram has now been merged with verbal semantics.

(Note: the verbal morphology diagram has now been merged with verbal semantics.)

- Martin Hilpert's lecture on Information Structure

Reading

- For a brief introduction to text linguistics, see Eep Talstra, “Text Linguistics”

- For discourse markers, see Marco Di Giulio, “Discourse Markers”

- For general overviews of information structure see the introductory chapters Manfred Krifka & Renate Musan, "Information Structure: Overview and Linguistic Issues," in The Expression of Information Structure, pp. 1-44 and Gregory Ward & Betty J. Birner, "Discourse Effects of Word Order Variation," in Semantics: Sentence and Information Structure, pp. 413-449.

- For meaning of focus see Jenneke van der Wal, “Diagnosing Focus,” in Studies in Language 40:2 (2016): 259-301.

- For the discourse contribution of interrogatives and imperatives see Sarah Murray, “Varieties of Update,” in Semantics and Pragmatics 7(2) (2014): 1-53. (Link)

- For related works within BH studies see §47 in Christo van der Merwe & Jacobus Naudé, A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar. London: Bloomsbury, 2017; Geoffrey Khan & Christo van der Merwe, “Towards a Comprehensive Model for Interpreting Word Order in Classical Biblical Hebrew,” in Journal of Semitic Studies LXV/2 (2020): 347-390; but for information structure and word order in poetry see Nicholas Lunn, Word-Order Variation in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: Differentiating Pragmatics and Poetics. Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2006; and Christo van der Merwe & Ernst Wendland, “Marked Word Order in the Book of Joel,” in Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 36/2 (2010): 109-130.

Theoretical Foundations

- For text coherence, memory and attention, see Elizabeth Robar, The Verb and the Paragraph in Biblical Hebrew: A Cognitive-Linguistic Approach. Leiden: Brill, 2015. 1-30.

- For discourse topic and point of view see pp. 120-136 of Wallace Chafe, Discourse, Consciousness and Time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994 and pp. 457-499 of Ronald Langacker, Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction. Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2008.

- For attention and perspective see pp. 92-116 of Thora Tenbrink, Cognitive Discourse Analysis: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- For topic-comment & thetic constructions see pp. 327-347 of William Croft, Morphosyntax: Constructions of the World’s Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Rubric (Version )

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Completeness |

|

| Quality of analysis |

|

| Engagement with secondary literature |

|

| Clarity of language |

|

| Formatting/Style |

|

Submitting your draft

Copy the text below into your forum submission post, entitled Macrosyntax - Psalm ###. After posting, change your post into a wiki post so the reviewers can check the boxes. To change your forum post into a wiki post, click on the three dot menu at the end of the text.

Click on the wrench.

Select "make wiki."

[Macrosyntax Layer Rubric Version ](https://psalms.scriptura.org/w/Macrosyntax#Rubric) |Guardian Review|Overseer Review|Final Checks|Description| | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||||**Completeness** |[ ]||| Every element required by the creator guidelines is included. |[ ]||| Subordination is marked. |[ ]||| Coordination and scope, where applicable, is marked. |[ ]||| Vocatives are marked, and their function is discussed in the notes section. |[ ]||| Other discourse markers, and their semantic scope, where applicable, are indicated and discussed in the notes section. |[ ]||| Direct speech is boxed. |[ ]|[ ]|| All cases of marked topic, marked focus, frame setters and thetic sentences are correctly indicated in the visual and explained in notes section. |[ ]|[ ]|| The scope of an activated topic, if applicable, is indicated. |[ ]|[ ]|| Every other instance of non-default word order for purposes of poetic structure is explained in the notes. |[ ]|[ ]|| Discourse discontinuities are indicated and justified in notes section. |[ ]|[ ]|| Translation is expanded where relevant according to the information structure. ||||**Quality of analysis** |[ ]||| Clause divisions correspond with divisions in the grammatical diagram. |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Any points of the analysis that are controversial and/or significant are thoroughly explained and defended in the notes section. |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Arguments for preferred interpretations are cogent. |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Discourse discontinuities are well-grounded in macrosyntactic evidence. ||||**Engagement with secondary literature** |[ ]|[ ]|| For areas of difficulty and debate, an effort was made to follow the discussion in the CG's appendix and engage with secondary sources (for example, Lunn [2006] and Khan & van der Merwe (2020) on word order; Di Giulio [2013] and Locatell [2017] on discourse markers and ''kî''; Miller [2010] and Kim [2022] on vocative positions). ||||**Clarity of language** |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Prose notes are clear and concise. |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Language is not too technical so as to be inaccessible to [Sarah](https://psalms.scriptura.org/w/Personas). ||||**Formatting/Style** |[ ]|[ ]|| All colours, fonts, and shapes match those which are given in the template and creator guidelines.

Previous Versions of these guidelines

These are the previous versions of the guidelines that mark significant milestones in our project history. Future versions will be numbered and will correspond to materials approved according to those guidelines.

- Tables format (Oct 2022)

- Text format (Nov 2022)

- Introduction of vocative positions (May 2023)— 0.9

Footnotes

- ↑ As it may be necessary to adjust the position of curves throughout the review process (e.g., if a clause division is missed or a discourse discontinuity should be changed), it may be advisable to only place the curves on the Hebrew side of the visual until final checks. Remember, also to group the curves in order to move them more efficiently on Miro.

- ↑ Left dislocation is to be differentiated from fronting in that, whereas fronting is simply placing a clausal constituent in clause-initial position, left-dislocated constituents are technically clause-external as they are resumed in the clause pronominally. Compare, I don't really like ice cream, but cake, I like (fronted) with I don't really like ice cream, but cake, I like it (left-dislocation). BHRG defines left-dislocation as "Topic announcing constructions" in that "An entity established as the topic of a subsequent utterance" (§48.2). Here are a few BH examples of left-dislocation (see BHRG §48 for more discussion): כִּ֣י׀ הַגּוֹיִ֣ם הָאֵ֗לֶּה אֲשֶׁ֤ר אַתָּה֙ יוֹרֵ֣שׁ אוֹתָ֔ם אֶל־מְעֹנְנִ֥ים וְאֶל־קֹסְמִ֖ים יִשְׁמָ֑עוּ וְאַתָּ֕ה לֹ֣א כֵ֔ן נָ֥תַן לְךָ֖ יְהוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֶֽיךָ׃ (Deut. 18:14); וַאֲנִ֖י הִנְנִ֣י בְיֶדְכֶ֑ם עֲשׂוּ־לִ֛י כַּטּ֥וֹב וְכַיָּשָׁ֖ר בְּעֵינֵיכֶֽם׃ (Jer 26:14). Note that the resumed constituent in the clause nucleus may continue the activated topic (see, e.g., Ps 23:4) or provide the focal material of the clause (see, e.g., Ps 38:11).

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.

- ↑ Though a misnomer, it is common among scholarship to refer to thetics as sentence focus, so they will share the same visual indication (bold) as constituent focus