Poetic Structure

- Grammar

- Semantics

- Exegetical Issues

- Discourse

- Poetics

- Synthesis

- Close-but-Clear

- Videos

- Post to wiki

- Style Guide

Version:

Overseer: Ryan Sikes

Introduction

The Psalms are poems, and attention to their poetic nature is necessary for properly understanding, truly appreciating, and faithfully translating them. As Wendland and Zogbo write, “These poems deserve careful treatment so that the real beauty and power of the original can be felt, and the complete message can be experienced, rather than simply understood. If we reduce poetry to prose, the biblical message may lose its effect and, in a very real way, be robbed of some of its truth. Consistently translating poetic lines into flat prose is not being faithful to the text. It does not provide a dynamic, literary or functionally equivalent translation.”[1]

Steps

Our poetics layer involves the following three steps:

- Line division. Divide the poem into lines and line groupings.

- Poetic macrostructure. Identify larger structures (strophes and stanzas) formed by combinations of lines and line groupings.

- Poetic features. Identify poetic features and their effects.

Poetic features are discussed on a separate page. This page will focus on line division and poetic macrostructure.

1. Line division

The line is the basic building block of Biblical Hebrew poetry.[2] One of the aims of this layer is to determine the line structure of the psalm (i.e., the number of lines in the psalm as well as where each line begins and ends). Several criteria are involved in determining the line structure.[3] These criteria are summarized in the following table:

| External Evidence | Internal Evidence |

|---|---|

| Pausal forms | Line length & balance |

| MT accents | Symmetry & parallelism |

| Manuscripts | Syntax |

- Copy the line division template from the template board.

- Copy the Hebrew text from OSHB and paste it into the relevant text box. Remove the verse numbers.

- For all preferred emended or revocalized Hebrew texts, replace the MT reading in the main text with the emended or revocalized Hebrew with asterisks on either side of the altered Hebrew text (e.g., *מֵחֹשֶׁךְ*). The asterisks should be colored purple if the change is a revocalization and blue if an emendation of the consonantal text. Do not supply accents for the altered Hebrew text. At the bottom of the visualiation, add a note for each emendation or revocalization referring to the primary discussion for each variant (usually a note in the grammar layer or an exegetical issue) and provide the MT for comparison. E.g., ** For the revocalization מֵחֹשֶׁךְ, see grammar note (MT: מַחְשָֽׁךְ). As you work, be sure to provide the appropriate markings for accents and pausal forms on the dispreferred text in your note.

- Copy the English CBC and paste it into the relevant text box. Remove the verse numbers. (Remember that both the Hebrew and the English text should be in Times New Roman.)

- Highlight (yelllow: #FEF445) all pausal forms in the Hebrew text.[4] A complete list of pausal forms in the Hebrew bible can be downloaded here. Do not highlight instances of nesigah (the retraction of word stress) that are not also pausal forms (e.g., אֲפִ֥יקֵי מַ֗יִם in Ps 18:16), though it might sometimes be helpful to note them in your notes section.

- Colour as red all of the accents which tend to correspond with line divisions.[5] These include the following six accents.

- silluq (e.g., יָשָֽׁב Ps. 1:1)

- 'ole weyored (e.g., חֶ֫פְצ֥וֹ Ps. 1:2 and פַּלְגֵ֫י מָ֥יִם Ps. 1:3)

- atnaḥ (e.g., הָרְשָׁעִ֑ים Ps. 1:4)[6]

- revia replacing atnaḥ (e.g., יֶהְגֶּ֗ה Ps. 1:2)[7]

- revia gadol preceded by a precursor (e.g., בְּעִתּ֗וֹ Ps. 1:3)[8]

- ṣinnor preceded by a precursor (e.g., הָלַךְ֮ Ps. 1:1).

- Insert a light grey pipe | at each clause boundary (regardless of whether the clauses are independent or subordinate). Refer to the grammatical diagram when identifying clause boundaries. Upon the completion of this step, the Hebrew text should look something like this:

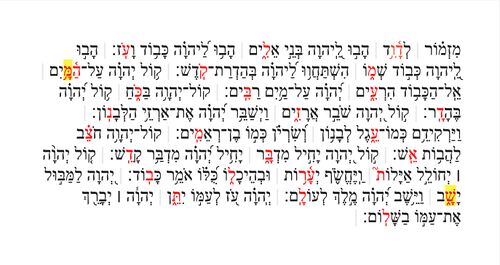

- Begin spacing out the text to indicate line divisions (see image below). At this point, the divisions should be based on (1) pausal forms, (2) accents, and (3) syntax (i.e., clause boundaries). The more these terminal markers coincide at a particular point, the more likely there is a line division at that point. Note that in some cases, the evidence will be conflicting or ambiguous. Further evidence is needed.

- To the right of each line of Hebrew text, list the number of prosodic words in blue. For this visual, we will define prosodic words in terms of the Masoretic tradition: any unit of text which is not divided by a space or which is joined by maqqef (or ole weyored) is a prosodic word.[9] E.g., כִּ֤י הִנֵּ֪ה הָרְשָׁעִ֡ים יִדְרְכ֬וּן קֶ֗שֶׁת contains 5 prosodic words; צַ֝דִּ֗יק מַה־פָּעָֽל contains two prosodic words; etc. The relevance of counting prosodic words is two-fold:

- The length of lines typically ranges between 2 and 5 prosodic words.[10] It may be possible for a line to contain more than 5 prosodic words, though such a line division would require justification on other grounds. If a line has more than 5 prosodic words, then bold the number (e.g. 6).

- Lines also tend to be balanced in relation to one another. Symmetrically-arranged line pairs in particular tend not to differ by more than one prosodic word.[11] Lines within a line grouping may at times be imbalanced, but this division of the text must be justified on other grounds.

- (Optional:) If some line divisions are still uncertain, it may be useful to consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. If a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences your decision to divide the text at a certain point, then place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

- Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS). Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls psalms manuscripts indicate line divisions.

- Septuagint (G). The line divisions in Rahlfs' edition are based on manuscript divisions, and they are generally reliable. Rahlfs usually notes alternate traditions of line division in the apparatus. Codex Sinaiticus may be viewed here.

- Masoretic Manuscripts (MT). Aleppo Codex (Psalms 15:1–25:1 missing); Sassoon Codex;[12] Berlin Qu. 680 (EC1); Or2373

- In cases where the line division is ambiguous or contested, record the reasons for your preferred division in the notes section of the template.

- Indicate verses (small groups of lines) by using additional spacing. Verses should be based on the Masoretic versification system unless there is good reason to do otherwise. Superscriptions should not be included in a verse.

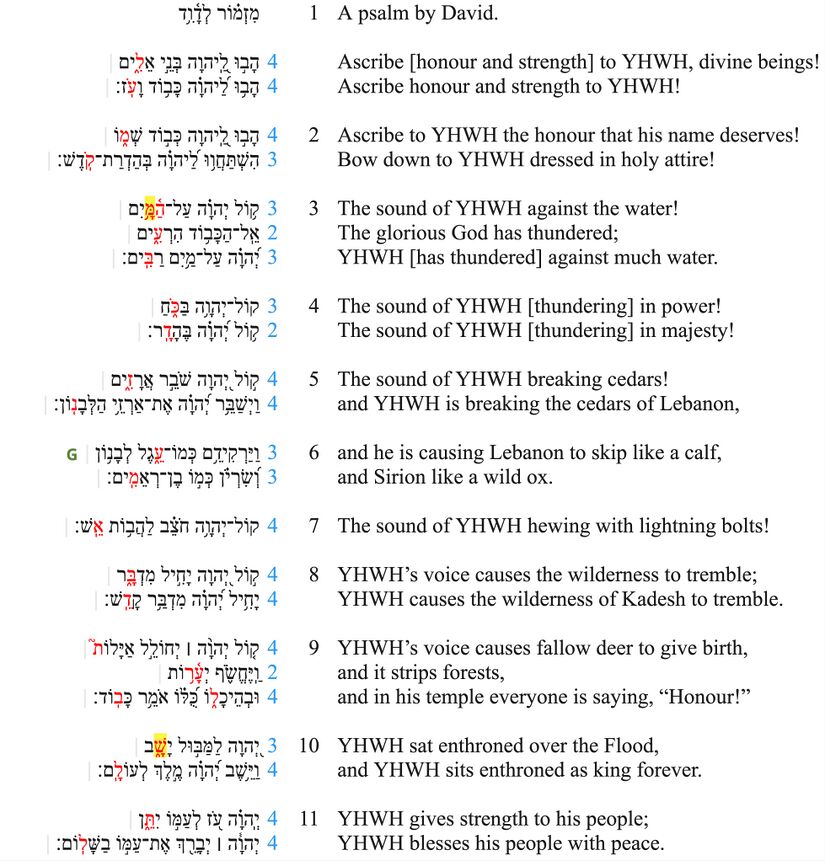

The final version should look something like the following:

- Ensure that CBC on the forum reflects the new line division.

2. Poetic Structure

In several of our layers so far (e.g., participant analysis, macrosyntax, speech act analysis), we have isolated one aspect of the text (e.g., participant shifts, syntax, speech acts) and determined breaks in the text based on that one aspect. In this visual, we take into account all aspects of the text in an attempt to synthesize all previous layers of analysis and to identify the poetic structure of the poem. The structure identified at this layer will be the structure seen in the "at-a-glance" visual for the psalm.

- Copy the poetic structure template from the templates board, and paste it onto the board for your psalm.

- Copy the previously completed "Line Divisions" visual and paste it into the "Poetic Structure" template. Remove all color formatting from the text as well as all clause-end markers, blue numbers and green symbols. The only things left should be the lineated Hebrew text, the lineated CBC text, and the verse numbers in between the two texts.

- Use grey boxes to group together units of text (see visual below). Because lines are already grouped together into line groupings by spacing, there is no need to place boxes around the line groupings. Use boxes to join line groupings together into larger units of text. Depending on the size of the psalm, these larger units may then be grouped together to form even larger units, up-to and including the entire psalm. When attempting to identify larger groupings of text, it is helpful to keep in mind some of the Gestalt Principles of perception.

- According to the principle of similarity, units of text that are similar to one another tend to be grouped together. The similarity may be syntactic, lexical, semantic, phonological, prosodic or based on a combination of these or other aspects of language.

- According to the principle of closure, "stimuli tend to be grouped together if they form a closed figure."[13] Poetic inclusios often function to bind together units of text into a larger unit.

- According to the principle of good continuation, patterns tend to "perpetuate themselves in the mental process of the perceiver."[14]

- If the identification of a structural unit is based on some similarity across that unit, then use a curly braces to bind together the grey box surrounding that unit, and briefly describe in bullet points the type of similarity (see visual below). If the point of similarity is a specific and localized textual feature which may be easily coloured, then colour the text accordingly and colour the curly brace to match it (see visual below). Do the same with inclusios and other structural devices based on the principle of symmetry (similar beginnings, similar endings, chiasms, etc) (see visual below).

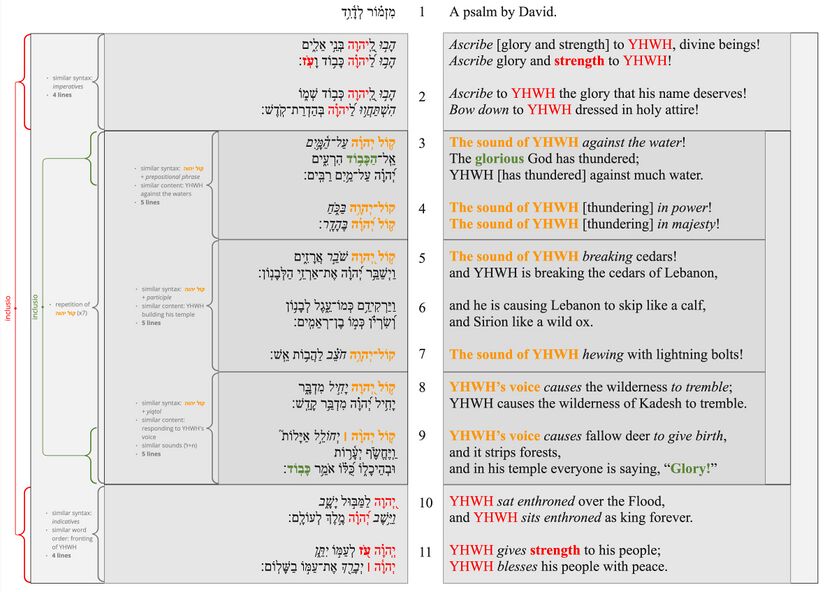

The Psalm 29 visual shows the following:

The Psalm 29 visual shows the following:

- The psalm is framed by an inclusio; it begins and ends with four-line unit containing the key term "strength" (עז) and the four-fold mention of YHWH's name.

- vv. 1-2 are bound together by similar syntax (imperatives).

- vv. 3-9 are bound together by the sevenfold repetition of the phrase קול יהוה. This large unit is also framed by an inclusio; it begins and ends with a tricolon that contains the word "glory".

- Within the unit of vv. 3-9, there are three sub-units, each of which is 5 lines long.

- vv. 3-4 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by prepositional phrases) and similar content (description of YHWH's battle against the waters).

- vv. 5-7 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by participles) and similar content (description of YHWH building his temple out of cedar and stone).

- vv. 8-9 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by finite verbs [yiqtols]), similar sounds (ח + ל), and similar content (description of creation responding to YHWH's voice).

- The final section (vv. 10-11) corresponds to the first and is further bound together by similar syntax (indicative verbs) and word order (fronting of YHWH).

Appendix: Structural Terminology

- We use the term line to refer to the basic building block of Biblical Hebrew Poetry. Other scholars have called this unit a hemistich, half-line, or verset. See footnote #2.

- We use the term verse to refer to a small grouping of lines, usually a group of two or three lines, though sometimes more. These groupings typically correspond to a normal (Masoretic) "verse." Other scholars refer to this unit as a "line group" or a "strophe" or describe it more specifically as a "bicolon" or "couplet", "tricolon or "triplet", etc. When referring to the length of the verse, we will use the terms "two-line verse," "three-line verse," etc.

- We use the term section to refer to a grouping of verses. Other scholars use terms such as "strophe," "stanza," "canticle" or "canto" depending on the size and hierarchical level of the grouping. We use the term "section" regardless of the size or hierarchical level of the grouping. The section might be small (two or three verses) or large (several verses). In many psalms, sections will also be embedded within other sections. In psalms like this, we use the term main section to specify the highest-level sections within a psalm and the term sub-section to specify any lower-level sections. There will sometimes be multiple levels of sub-sections within a psalm, but the context should make clear which sub-section is being discussed. E.g., "Psalm X consists of two main sections (vv. 1-15; vv. 16-20). The first main section further divides into two sub-sections (vv. 1-8; vv. 9-15), and each of these sub-sections further divides into two smaller sub-sections (vv. 1-4; vv. 5-8; vv. 9-12; vv. 13-15)."

- We use the term psalm to refer to the entire poem.

We can illustrate the use of these terms with reference to the Psalm 29 visual (above). Psalm 29 (a single "psalm") consists of three main sections (vv. 1-2; vv. 3-9; vv. 10-11). The middle section (vv. 3-9) further divides into three sub-sections (vv. 3-4; vv. 5-6; vv. 10-11). Every section in the psalm consists of two verses, and every verse in the psalm consists of two lines, except for v. 3 and v. 9 which are three-line verses.

Help

Good Examples

Common Mistakes

- Marking features that are not directly related to the poetic structure. The purpose of the poetic structure visual is to make a visual argument for our preferred poetic structure. The purpose is not to mark every repetition in the psalm. Only mark those repetitions that have a clear structural function. Everything that is marked in the visual should be explained with a corresponding bullet-point note.

- Marking too many structural features. When too much of the text is marked, it becomes difficult to process the visual. The poetic structure visual should be as concise as possible, focusing on the most important aspects of the poetic structure. The most prominent structural markers should be the most visually prominent, and the least prominent ones should be the least visually prominent. The reader should be able to get the most important information from the visual with only a quick glance.

- Not using the visual tools (boxes and braces) according to their purpose. Carefully study the examples given in the guidelines and makes sure your use of boxes and braces is consistent with them.

Additional Resources

- Auffret, Pierre. E.g. Voyez de vos yeux. Étude structurelle de ... psaumes...

- Fokkelman, J. P. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Hermeneutics and Structural Analysis. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum, 2000.

- ———. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis. Studia semitica Neerlandica 43. Assen: Royal van Gorcum, 2003.

- Labuschagne, C.J. “Numerical Features of the Psalms, a Logotechnical Quantitative Structural Analysis.” DataverseNL, 2020.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter. Oudtestamentische studiën = Old Testament studies v. 53. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2006.

- ———. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry II, Psalms 42-89. Oudtestamentische studien = Old Testament studies v. 57. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2010.

- ———. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1. Oudtestamentische studiën = Old Testament studies v. 63. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2014.

Book Summaries:

- Unparalleled Poetry

- Hebrew Verse Structure

- Poems, Poets, Poetry

- Vertical Grammar of Parallelism in Biblical Hebrew

Rubric (Version )

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Completeness |

|

| Quality of analysis |

|

| Engagement with secondary literature |

|

| Clarity of language |

|

| Formatting/Style |

|

Submitting your draft

Copy the text below into your forum submission post, entitled Poetic Structure - Psalm ###. After posting, change your post into a wiki post so the reviewers can check the boxes. To change your forum post into a wiki post, click on the three dot menu at the end of the text.

Click on the wrench.

Select "make wiki."

[Poetic Structure Layer Rubric Version ](https://psalms.scriptura.org/w/Poetic_Structure#Rubric) |Guardian Review|Overseer Review|Final Checks|Description| | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||||**Completeness** |[ ]||| Each element required by the creator guidelines has been included. |[ ]||| Complete line division visual. |[ ]||| Complete poetic macrostructure visual with accompanying prose. |[ ]|[ ]|| Difficulties and alternatives are explained with prose notes. ||||**Quality of analysis** |[ ]|[ ]|| Pausal forms and accents have been correctly identified. |[ ]||| Prosodic words have been counted correctly. |[ ]|[ ]|| Line division is based on a well-balanced combination of the criteria presented in the guidelines (external and internal evidence). |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Poetic section divisions and groupings are well grounded in compelling evidence. ||||**Engagement with secondary literature** |[ ]|[ ]|| Secondary sources (esp. van der Lugt and Fokkelman) are cited where relevant. ||||**Clarity of language** |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Prose notes are clear and concise. |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Bullet point notes in the poetic structure visual are as concise as possible. |[ ]|[ ]|[ ]| Language is not too technical so as to be inaccessible to [Sarah](https://psalms.scriptura.org/w/Personas). ||||**Formatting/Style** |[ ]||| The visuals are based on the templates in MIRO and so use the correct font sizes, styles, and colours. |[ ]||| The line division visual is properly spaced. |[ ]|[ ]|| The poetic structure visual uses the visual tools provided (grey boxes, grey braces, coloured braces, bullet points) and uses each tool according to its purpose. |[ ]|[ ]|| The positioning of the various elements of the poetic structure visual (e.g., boxes, braces, and bullet-points) matches that of the example in the guidelines (Ps. 29). |[ ]|[ ]|| The poetic structure visual is clear, concise and focused on the points which are most relevant to the structure. |[ ]||| The poetic structure visual is as narrow as possible.

Previous Versions of these guidelines

These are the previous versions of the guidelines that mark significant milestones in our project history. Future versions will be numbered and will correspond to materials approved according to those guidelines.

- Removal of line length visual (Jan 2024)— 0.9

- Addition of appendix (Sep 2024)— 1.0

Footnotes

- ↑ Wendland and Zogbo 2020, 8.

- ↑ What Biblical scholars have variously referred to as stich, hemistich, colon, verset, half-line, etc. is here referred to as “line” because (1) this term has “a long-standing scholarly tradition of use within biblical studies" (Dobbs-Allsopp, 2015, 22); (2) this is the term used for this phenomenon “in the discipline of Western literary criticism” (Dobbs-Allsopp 2015, 22); (3) “this is the terminology used in discussing other traditions of poetry throughout the world” (Wendland and Zogbo, 2020, 22). For more on the concept of the poetic line, see the book summary of Unparalleled Poetry.

- ↑ “Line structure in a given poem emerges holistically and heterogeneously. Potentially, a myriad of features (formal, semantic, linguistic, graphic) may be involved. They combine, overlap, and sometimes even conflict with one another… Thus what is called for is a patient working back and forth between various levels and phenomena, through the poem as a whole, considering the contribution, say, of pausal forms alongside and in combination with other features” (Dobbs-Allsopp 2015, 56).

- ↑ Pausal forms often mark the end of a poetic line. See E.J. Revell, “Pausal Forms and the Structure of Biblical Hebrew Poetry,” Vetus Testamentum 31, no. 2 (1981): 186–199.

- ↑ The following analysis of the accents is based on Sanders and de Hoop, forthcoming §1.4.2. According to Sanders and de Hoop, the basic purpose of the accents is to guide the recitation of the text (see Sanders and de Hoop, "The System of Masoretic Accentuation: Some Introductory Issues") and not necessarily to mark poetic lines. Thus, the relationship between the accents and poetic line division is indirect. See the discussion on the Pericope website.

- ↑ When atnaḥ follows 'ole weyored, it is less likely to correspond with the end of a line.

- ↑ This accent is also known as "defective revia mugraš" or "revia mugraš without gereš".

- ↑ "We define a precursor as a disjunctive accent that is subordinate to the following disjunctive accent and subdivides the domain of that following accent" (Sanders and de Hoop, forthcoming §1.3)

- ↑ Krohn defines prosodic words as "i) unbound orthographic words that have at least one full syllable (CV, where V is not a shewa), or ii) orthographic words joined together by cliticization (Krohn 2021, 103).

- ↑ Cf. Krohn 2021:103. According to Geller, “lines contain from two to six stresses, the great majority having three to five” (NPEPP, 1998: 510). Hrushovski suggests a narrower range of two to four stresses (“Prosody, Hebrew,” 1961).

- ↑ Emmylou Grosser notes in her analysis of Judges 5 and the Balaam Oracles of Num. 23-24 that symmetrically-arranged line pairs tend to have “either equal stresses, or stresses unequal by one with balance of syllables deviating by no more than one” (Grosser: “Symmetry” 2021). Given this tendency toward rhythmic balance, Geller concludes that “passages with such symmetry form an expectation in the reader’s mind that after a certain number of words a caesura or line break will occur… The unit so delimited is the line. So firm is the perceptual base that long clauses tend to be analyzed as two enjambed lines” (Geller, "Hebrew Prosody", NPEPP, 509-510).

- ↑ Psalms begin on Folio 632.

- ↑ Grosser Unparalleled Poetry 2023.

- ↑ Grosser Unparalleled Poetry 2023.