Poetic Structure

- Grammar

- Semantics

- Exegetical Issues

- Discourse

- Poetics

- Synthesis

- Close-but-Clear

- Videos

- Post to wiki

Introduction

So far in our layer-by-layer analysis, we have analyzed the grammar and semantics of various psalms as well as the way in which these aspects of the language are manipulated for pragmatic effect. But we have yet to explore the Psalms as poetry. This aspect is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language.

“These poems deserve careful treatment so that the real beauty and power of the original can be felt, and the complete message can be experienced, rather than simply understood. If we reduce poetry to prose, the biblical message may lose its effect and, in a very real way, be robbed of some of its truth. Consistently translating poetic lines into flat prose is not being faithful to the text. It does not provide a dynamic, literary or functionally equivalent translation.”[1]

Steps

Our poetics layer involves the following four steps:

- Line division. Divide the poem into lines and line groupings.

- Line length. Measure the length of each line and look for patterns in line-length.

- Poetic macrostructure. Identify larger structures (strophes and stanzas) formed by combinations of lines and line groupings.

- Poetic features. Identify poetic features and their effects.

1. Line division

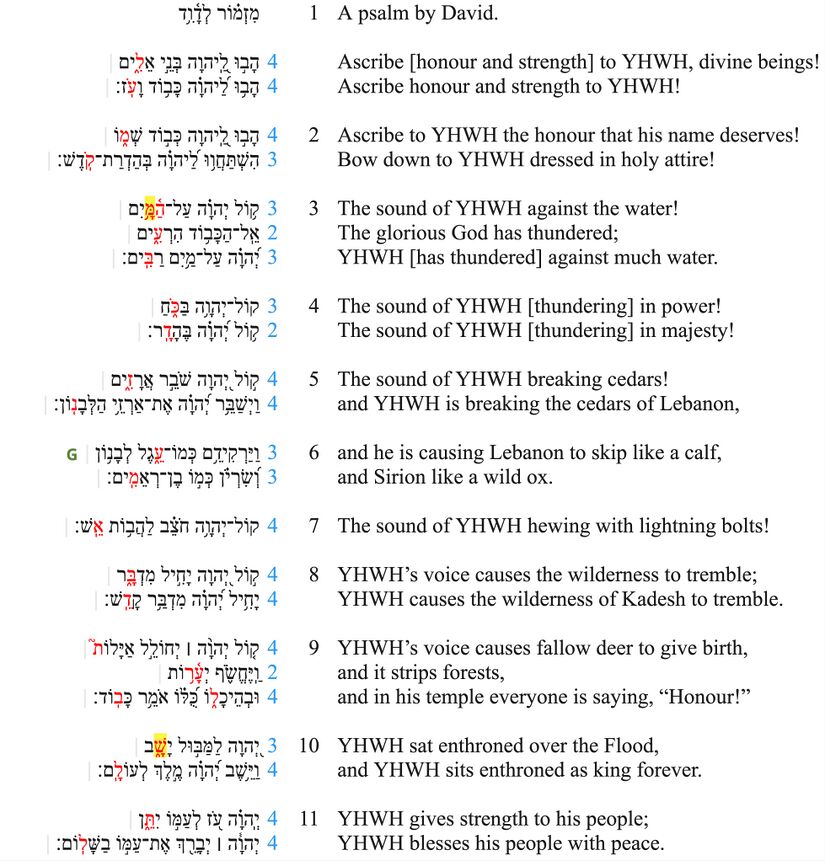

The line is the basic building block of Biblical Hebrew poetry.[2] One of the aims of this layer is to determine the line-structure of the psalm (i.e., the number of lines in the psalm as well as where each line begins and ends). Several criteria are involved in determining the line-structure.[3] These criteria are summarized in the following table:

| External Evidence | Internal Evidence |

|---|---|

| Pausal forms | Line length & balance |

| MT accents | Symmetry & parallelism |

| Manuscripts | Syntax |

- Copy the line division template from the template board.

- Copy the Hebrew text from OSHB and paste it into the relevant text box. Remove the verse numbers.

- Copy the English CBC and paste it into the relevant text box. Remove the verse numbers.

- Highlight all pausal forms in the Hebrew text.[4] A complete list of pausal forms in the Hebrew bible can be downloaded here.

- Colour as red all of the accents which tend to correspond with line divisions.[5] These include (1) silluq (e.g., ); (2) 'ole weyored (e.g., ); (3) atnaḥ (e.g., );[6] (4) revia replacing atnaḥ[7] (e.g., ); (5) revia gadol preceded by a precursor;[8] (6) ṣinnor preceded by a precursor.

- Insert a pipe | at each clause boundary (regardless whether the clauses are independent or subordinate). Refer to the grammatical diagram when identifying clause boundaries. Upon the completion of this step, the Hebrew text should look something like this:

- Begin spacing out the text to indicate line divisions (see image below). At this point, the divisions should be based on (1) pausal forms, (2) accents, and (3) syntax (i.e., clause boundaries). The more these terminal markers coincide at a particular point, the more likely is a line division at that point. Note that in some cases, the evidence will be conflicting or ambiguous. Further evidence is needed.

- To the right of each line of Hebrew text, list the number of prosodic words in blue. For this visual, we will define prosodic words in terms of the Masoretic tradition: any unit of text which is not divided by a space or which is joined by maqqef (or ole weyored) is a prosodic word.[9] E.g., כִּ֤י הִנֵּ֪ה הָרְשָׁעִ֡ים יִדְרְכ֬וּן קֶ֗שֶׁת contains 5 prosodic words; צַ֝דִּ֗יק מַה־פָּעָֽל contains two prosodic words; etc. The relevance of counting prosodic words is two-fold:

- The length of lines typically ranges between 2 and 5 prosodic words.[10] It may be possible for a line to contain more than 5 prosodic words, though such a line division would require justification on other grounds. If a line has more than 5 prosodic words, then bold the number (e.g. 6).

- Lines also tend to be balanced in relation to one another. Specifically, lines within a line grouping tend not to differ by more than one prosodic word.[11] Lines within a line grouping may at times be imbalanced, but this division of the text must be justified on other grounds.

- (Optional:) If some line divisions are still uncertain, it may be useful to consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. If a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences your decision to divide the text at a certain point, then place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

- Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS). Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls psalms manuscripts indicate line divisions.

- Septuagint (G). The line divisions in Rahlfs' edition are based on manuscript divisions, and they are generally reliable. Rahlfs sometimes notes alternate traditions of line division in the apparatus. The Codex Sinaiticus may be viewed here.

- Masoretic Manuscripts (MT). Aleppo Codex; Berlin Qu. 680 (EC1); Or2373

- In cases where the line division is ambiguous or contested, record the reasons for your preferred division in the notes section of the template.

- Finally, indicate line-groupings by using additional spacing. Line groupings should be based on the Masoretic versification system (one verse = one line grouping) unless there is good reason to do otherwise. Superscriptions should not be included in a line grouping.

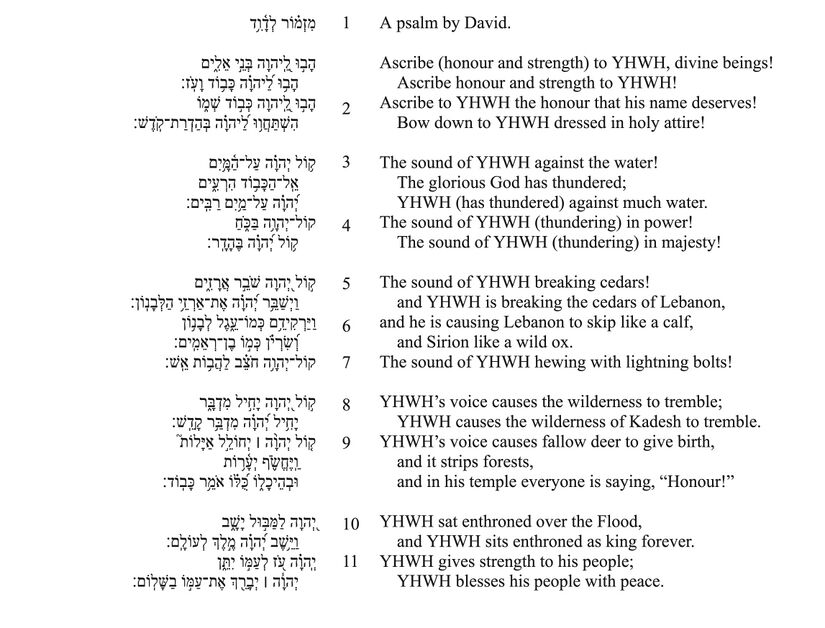

The final version should look something like the following:

2. Line Length

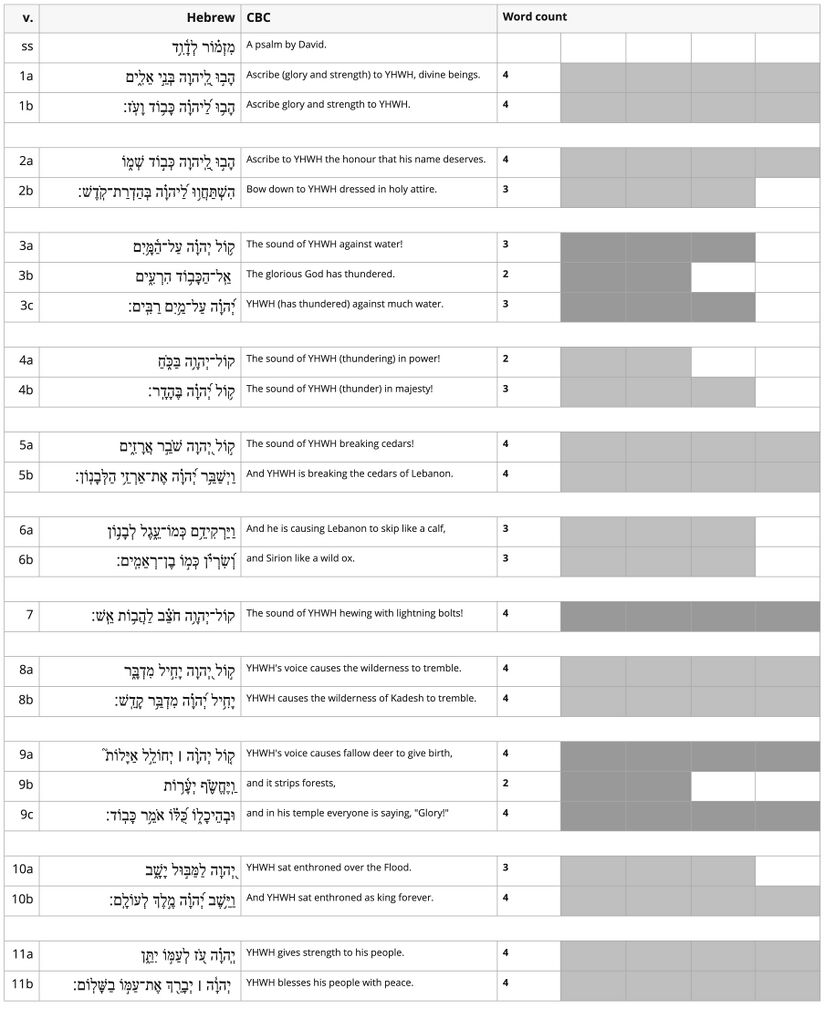

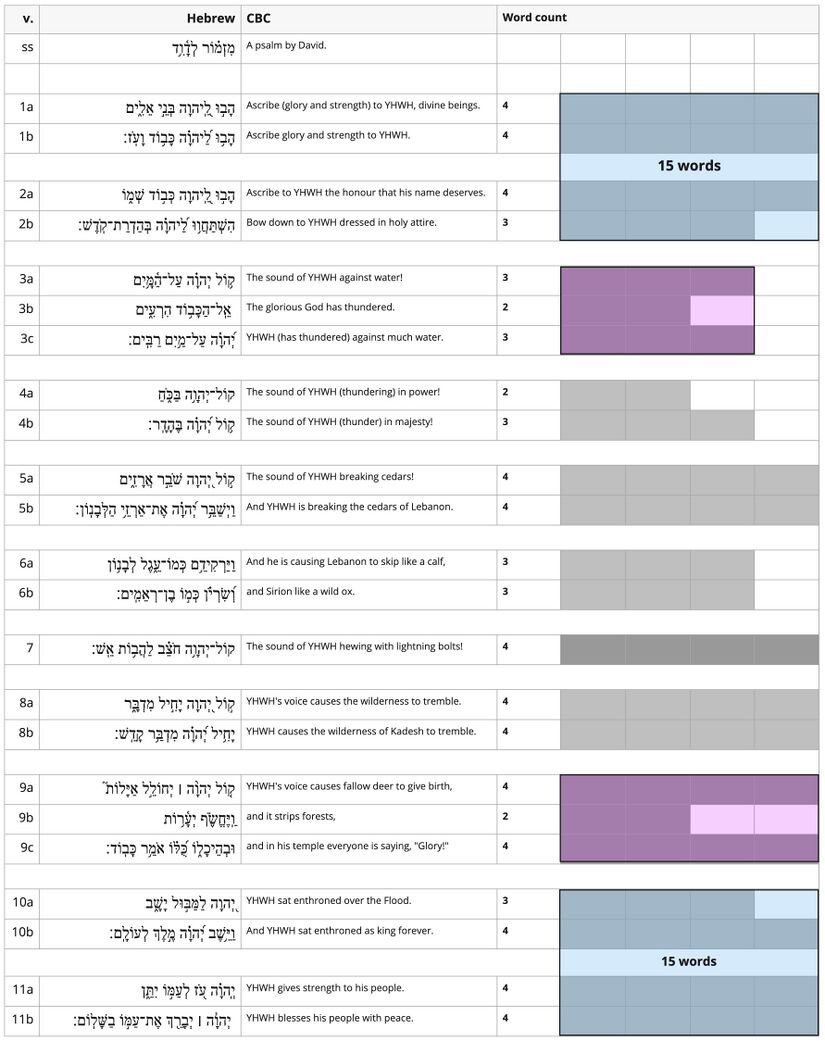

- Copy the line length template from the template board.

- Copy and paste the Hebrew text of the psalm into the "Hebrew" column, one poetic line per columnar row.

- Copy and paste the CBC into the "CBC" column, one poetic line per columnar row.

- In the far-left column ("v.") include verse/line numbers (1a, 1b, etc.; ss for superscription).

- Insert a blank row after each line grouping.

- In the first column under the heading "Word count," list the number of prosodic words in each line.

- For the remaining columns under the heading "Word count," shade the appropriate number of cells in each row, one cell per prosodic word. (Use gray #808080, shaded at 50% for line groupings that consist of two lines and 80% for line groupings that consist of more or less than two lines). Upon the completion of this step, the visual should look something like the following:

- Identify and visualize any potential patterns. For example, in Ps. 29, the first four lines have the same number of words and a similar patterning as the last four lines. Verses 3 and 9 are also similar in that they are both line triples (tricola) in which the A and C lines are the same length and the middle B line is shorter.

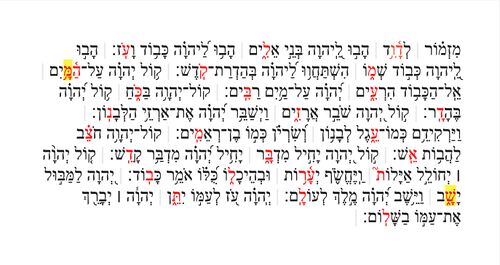

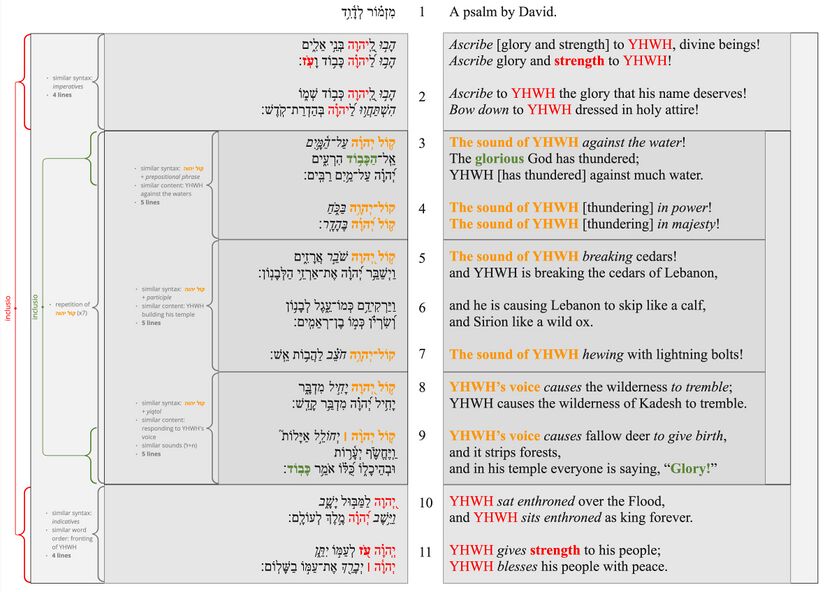

3. Poetic Structure

In several of our layers so far (e.g., participant analysis, macrosyntax, speech act analysis), we have isolated one aspect of the text (e.g., participant shifts, syntax, speech acts) and determined breaks in the text based on that one aspect. In this visual, we take into account all aspects of the text in an attempt to synthesize all previous layers of analysis and to identify the poetic structure of the poem. The structure identified at this layer will be the structure seen in the "at-a-glance" visual for the psalm.

- Copy the poetic structure template from the templates board, and paste it onto the board for your psalm.

- Copy the previously completed "Line Divisions" visual and paste it into the "Poetic Structure" template. Remove all color formatting from the text as well as all clause-end markers, blue numbers and green symbols. The only things left should be the lineated Hebrew text, the lineated CBC text, and the verse numbers in between the two texts.

- Use grey boxes to group together units of text (see visual below). Because lines are already grouped together into line groupings by spacing, there is no need to place boxes around the line groupings. Use boxes to join line groupings together into larger units of text. Depending on the size of the psalm, these larger units may then be grouped together to form even larger units, up-to and including the entire psalm. When attempting to identify larger groupings of text, it is helpful to keep in mind some of the Gestalt Principles of perception.

- According to the principle of similarity, units of text that are similar to one another tend to be grouped together. The similarity may be syntactic, lexical, semantic, phonological, prosodic or based on a combination of these or other aspects of language.

- According to the principle of closure, "stimuli tend to be grouped together if they form a closed figure."[12] Poetic inclusios often function to bind together units of text into a larger unit.

- According to the principle of good continuation, patterns tend to "perpetuate themselves in the mental process of the perceiver."[13]

- If the identification of a structural unit is based on some similarity across that unit, then use a curly braces to bind together the grey box surrounding that unit, and briefly describe in bullet points the type of similarity (see visual below). If the point of similarity is a specific and localized textual feature which may be easily coloured, then colour the text accordingly and colour the curly brace to match it (see visual below). Do the same with inclusios and other structural devices based on the principle of symmetry (similar beginnings, similar endings, chiasms, etc) (see visual below).

The Psalm 29 visual shows the following:

The Psalm 29 visual shows the following:

- The psalm is framed by an inclusio; it begins and ends with four-line unit containing the key term "strength" (עז) and the four-fold mention of YHWH's name.

- vv. 1-2 are bound together by similar syntax (imperatives).

- vv. 3-9 are bound together by the sevenfold repetition of the phrase קול יהוה. This large unit is also framed by an inclusio; it begins and ends with a tricolon that contains the word "glory".

- Within the unit of vv. 3-9, there are three sub-units, each of which is 5 lines long.

- vv. 3-4 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by prepositional phrases) and similar content (description of YHWH's battle against the waters).

- vv. 5-7 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by participles) and similar content (description of YHWH building his temple out of cedar and stone).

- vv. 8-9 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by finite verbs [yiqtols]), similar sounds (ח + ל), and similar content (description of creation responding to YHWH's voice).

- The final section (vv. 10-11) corresponds to the first and is further bound together by similar syntax (indicative verbs) and word order (fronting of YHWH).

See other examples of Poetic Structure visuals at the links below

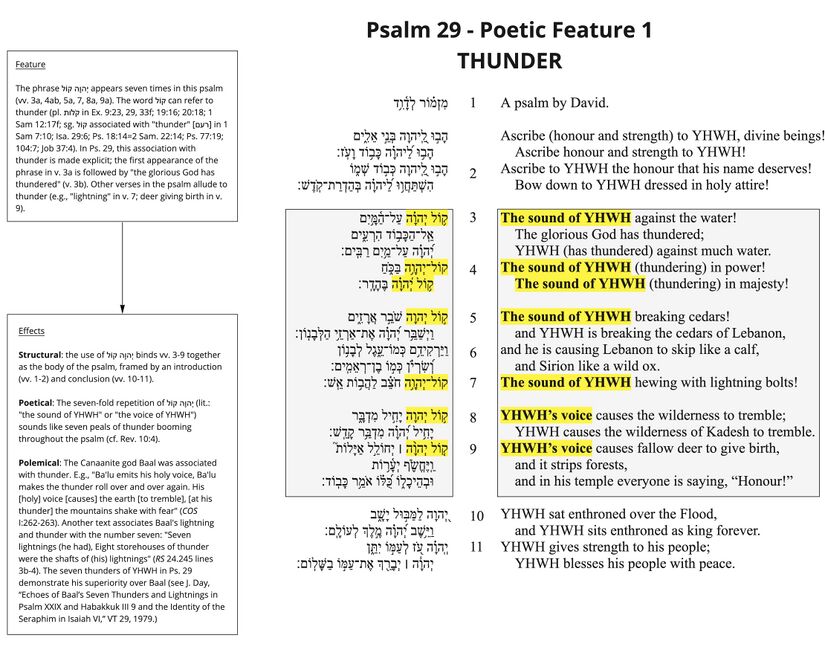

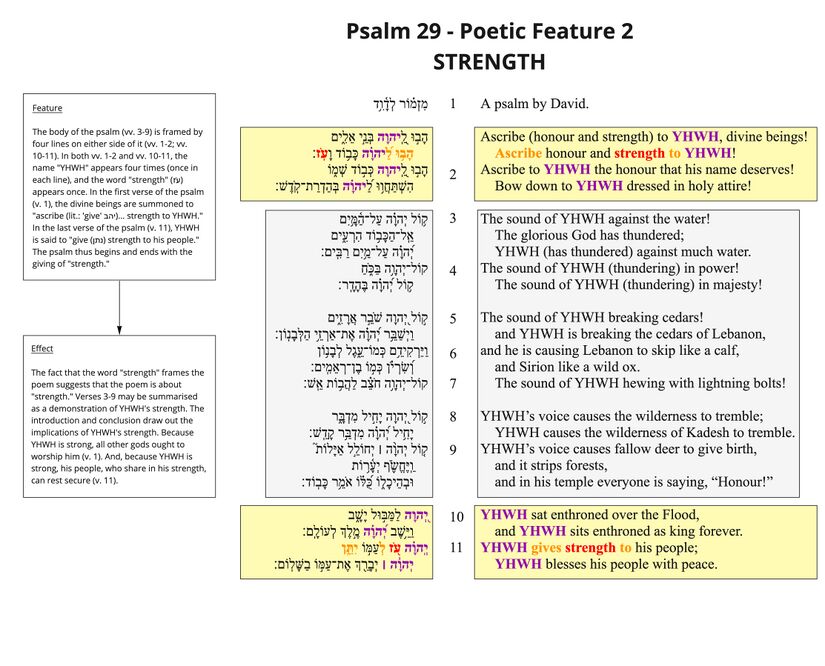

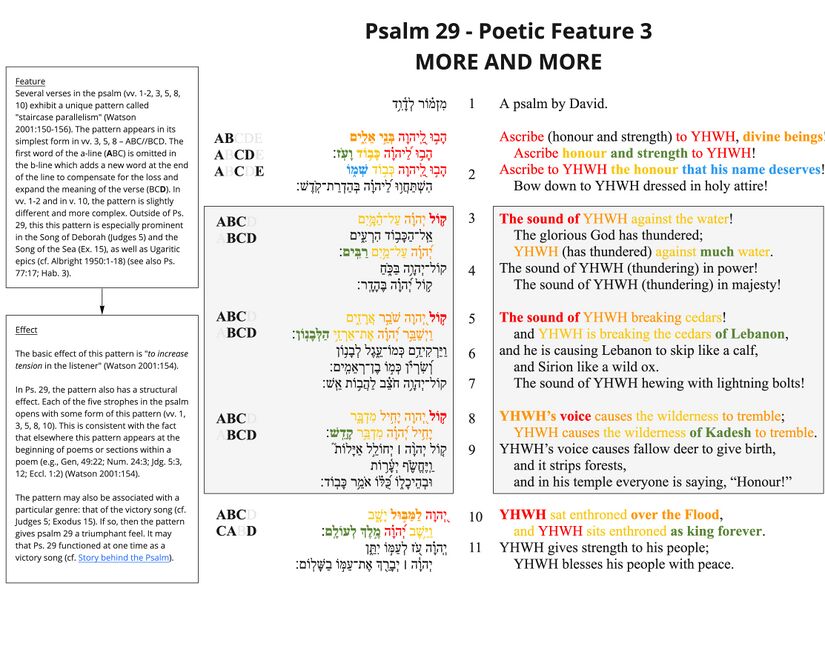

4. Poetic Features

- Copy the poetic features template from the template board and paste it onto your MIRO board.

- Copy the Hebrew-English text from the Poetic Structure visual and paste it onto the template. Delete all grey boxes and braces, and clear all special formatting of the text (e.g., bold, colour).

- Based on the Poetic Structure analysis, visually combine the lines of the text into poetic-paragraphs / strophes by deleting the space between line groupings that belong to the same paragraph (see visual below). Indent all b-lines, c-lines, and d-lines to visually indicate line-groupings within the strophes (see visual below). Indent (TAB) twice for b/c/d-lines in the Hebrew text and once for the CBC English text. At this point, the text should look something like the following:

- Copy and paste the template with the Hebrew/English text inside of it three times (one for each poetic feature).

- Now you are ready to identify the top three poetic features of the psalm. Given the unique artistry of each poem, there is no mechanical process for identifying the most significant poetic features. This identification requires thoughtful and prolonged meditation on the psalm as well as a general familiarity with Hebrew poetry and an expectation of the kinds of features Hebrew poems are likely to exhibit.[14] Nevertheless, some general guidelines for identifying the top poetic features may be given:

- Is the Psalm as a whole arranged in a pattern (e.g., acrostic, chiastic, etc.)? If so, then this will likely qualify as a top poetic feature.

- Do noticeable and meaningful correspondences function to connect lines or strophes across the Psalm? If so, then this may qualify as a top poetic feature. The connections may be formed by repeated roots, repeated sounds, repeated semantic domains, repeated rhythmic patterns, repeated syntactic structures, (etc.) or a combination of various elements. (See e.g., Ps. 1 "No Standing"; Ps. 2 "Think Again"; Ps. 3 "Rise and Rescue; Ps. 4 "Doubles"; Ps. 6 "Repetition, Resolution, and Reversal"

- How does the author use imagery (not only figurative language [metaphors] but also concrete non-figurative images)? Do the images relate to one other in meaningful ways? (See e.g., Ps. 1 "Footsteps", Ps. 2 "Heaven and Earth and In-Between"; Ps. 4 "A New Day Dawns".

- How does the author use sound to form connections, to signal points of prominence, or to create certain moods or affects? (See e.g., Ps. 1 "Opposite direction"; Ps. 2 "Son of God"; Ps. 3 "Response to Taunts"

- Are there any points of prominence in the Psalm (i.e., place where poetic features cluster)? (See e.g., Ps. 3 "The Sound of Silencing"; "The Heights of Poetry and the Depths of Pain; Ps. 150 "Poetic Party"

- The above questions and categories by no means exhaust the kinds of poetic features in the psalms. Some of the most fascinating poetic features do not fit in any of the above categories (or they belong to multiple categories at once). See e.g., Ps. 6 Death and Resurrection, Ps. 150 "Overflowing praise".

- Visualise each poetic feature on MIRO using whatever visual means are most effective (e.g., bold, underline, italics, colours, highlights, shapes, etc.).

- Describe the feature in the text box labeled "Feature." This is purely descriptive and minimally interpretive. Simply describe the feature which you have visualised.

- Describe the effect(s) of the feature in the text box labeled "Effects" (see examples in the above links).

- Give the poetic feature a memorable name.

Examples

References

- ↑ Wendland and Zogbo 2020:8.

- ↑ What Biblical scholars have variously referred to as stich, hemistich, colon, verset, half-line, etc. is here referred to as “line” because (1) this term has “a long-standing scholarly tradition of use within biblical studies" (Dobbs-Allsopp, 2015:22); (2) this is the term used for this phenomenon “in the discipline of Western literary criticism” (Dobbs-Allsopp, 2015:22); (3) “this is the terminology used in discussing other traditions of poetry throughout the world” (Wendland and Zogbo, 2020:22). For more on the concept of the poetic line, see the book summary of Unparalleled Poetry.

- ↑ “Line structure in a given poem emerges holistically and heterogeneously. Potentially, a myriad of features (formal, semantic, linguistic, graphic) may be involved. They combine, overlap, and sometimes even conflict with one another… Thus what is called for is a patient working back and forth between various levels and phenomena, through the poem as a whole, considering the contribution, say, of pausal forms alongside and in combination with other features” (Dobbs-Allsopp 2015:56).

- ↑ Pausal forms often mark the end of a poetic line. See E.J. Revell, “Pausal Forms and the Structure of Biblical Hebrew Poetry,” Vetus Testamentum 31, no. 2 (1981): 186–199.

- ↑ The following is based on Sanders and de Hoop, forthcoming §1.4.2.

- ↑ When atnaḥ follows 'ole weyored, it is less likely to correspond with the end of a line.

- ↑ This accent is also known as "defective revia mugraš" or "revia mugraš without gereš".

- ↑ "We define a precursor as a disjunctive accent that is subordinate to the following disjunctive accent and subdivides the domain of that following accent" (Sanders and de Hoop, forthcoming §1.3)

- ↑ Krohn defines prosodic words as "i) unbound orthographic words that have at least one full syllable (CV, where V is not a shewa), or ii) orthographic words joined together by cliticization (Krohn 2021:103).

- ↑ Cf. Krohn 2021:103. According to Geller, “lines contain from two to six stresses, the great majority having three to five” (NPEPP, 1998: 510). Hrushovski suggests a narrower range of two to four stresses (“Prosody, Hebrew,” 1961).

- ↑ Emmylou Grosser notes in her analysis of Judges 5 and the Balaam Oracles of Num. 23-24 that line pairs tend to have “either equal stresses, or stresses unequal by one with balance of syllables deviating by no more than one” (Grosser: “Symmetry” 2021). Given this tendency toward rhythmic balance, Geller concludes that “passages with such symmetry form an expectation in the reader’s mind that after a certain number of words a caesura or line break will occur… The unit so delimited is the line. So firm is the perceptual base that long clauses tend to be analyzed as two enjambed lines” (Geller, "Hebrew Prosody", NPEPP, 509-510).

- ↑ Grosser Unparalleled Poetry 2022:247.

- ↑ Grosser Unparalleled Poetry 2022:226.

- ↑ For the latter, see e.g., Wilfred Watson, Classical Hebrew Poetry: A Guide to its Techniques (Sheffield Academic Press: Sheffield), 2001; Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry; Adele Berlin, The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism