Verbal Semantics

- Grammar

- Semantics

- Exegetical Issues

- Discourse

- Poetics

- Synthesis

- Close-but-Clear

- Videos

- Post to wiki

A fuller discussion may be found here.

Key Concepts

This visualisation focuses on the relationship between verbs, time and modality. These are important categories for interpretation and translation, and how one analyses a verb can have a significant effect on how it is rendered. For example, notice how differently this selection of English versions translates the same verbs in Ps 3:8:

- הִכִּ֣יתָ אֶת־כָּל־אֹיְבַ֣י לֶ֑חִי // שִׁנֵּ֖י רְשָׁעִ֣ים שִׁבַּֽרְתָּ׃

- You strike . . . You shatter . . . (ESV, GNT)

- You have struck . . . You have shattered . . . (KJV, NASB)

- Strike . . . ! Shatter . . . ! (NIV, NLT, CEB)

- You will strike . . . You will shatter . . . (NET)

Tense

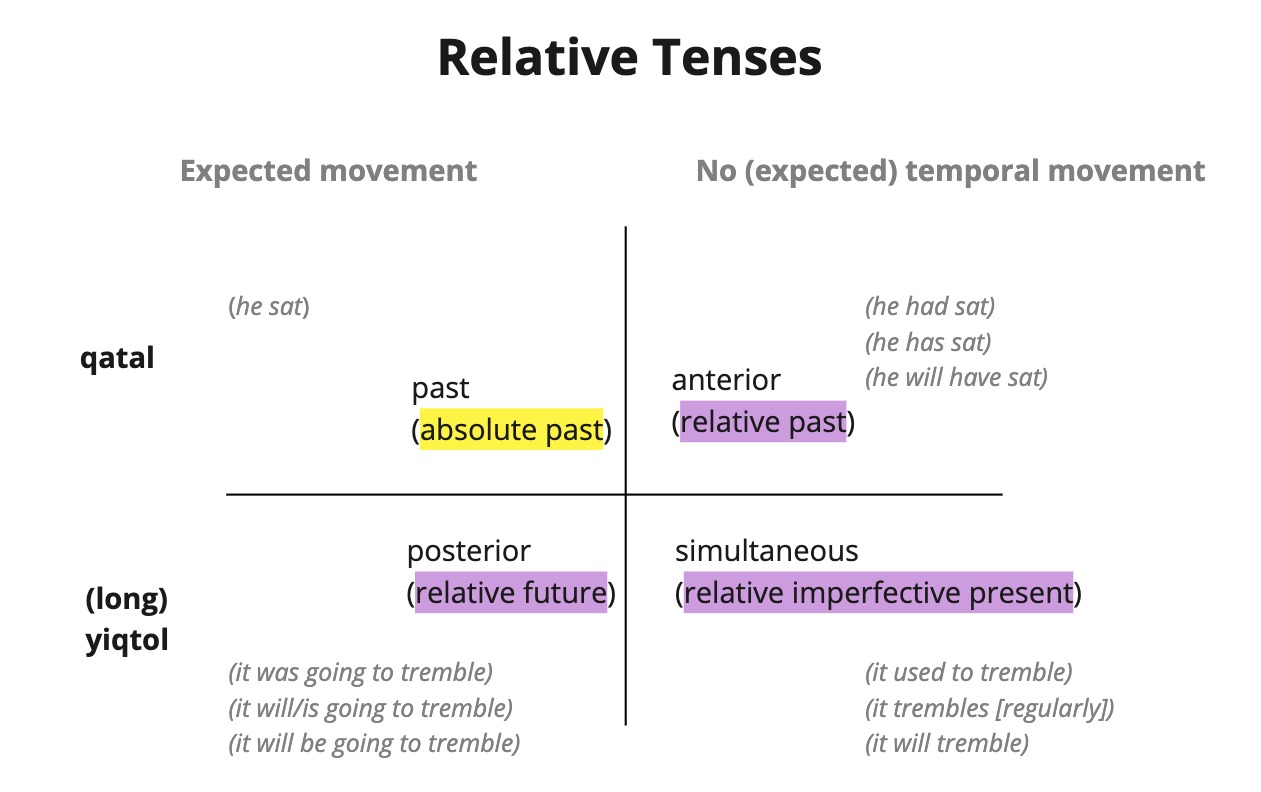

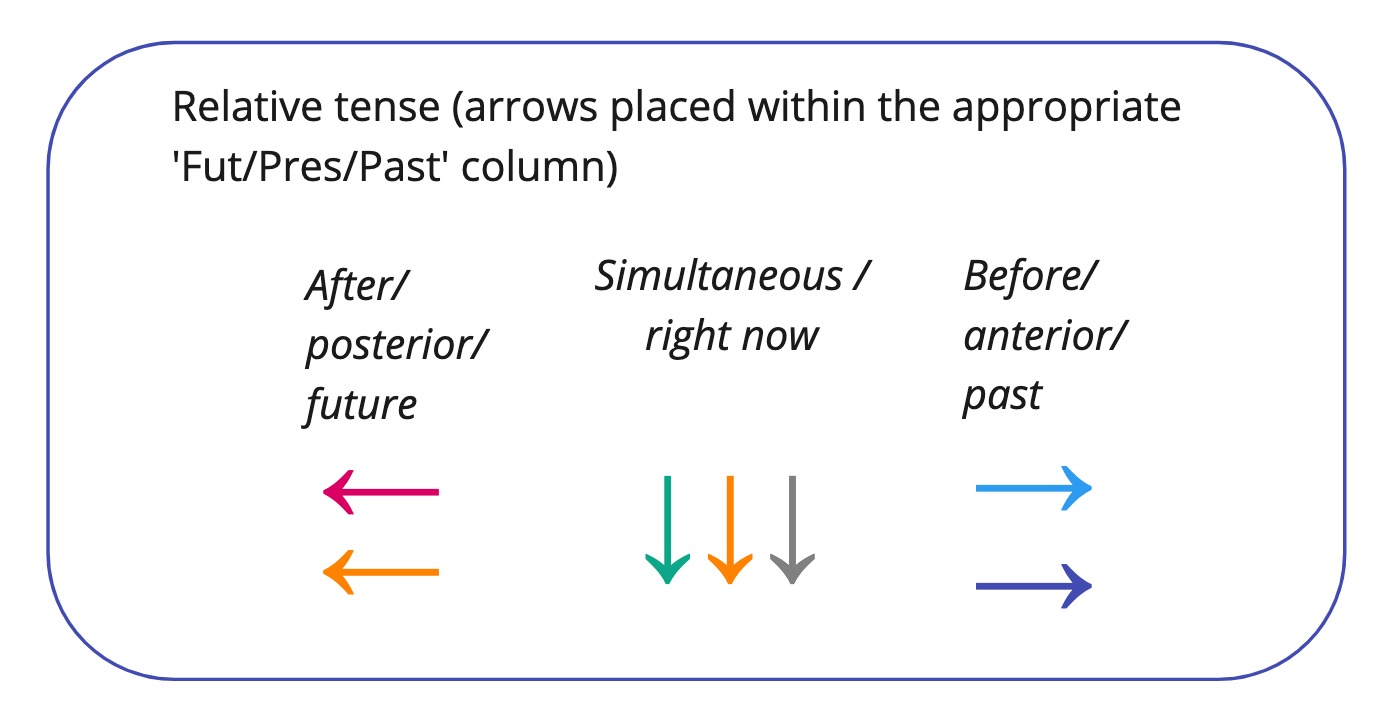

- Relative tense: a situation’s location in time relative to a given reference point (anterior, simultaneous, or posterior)

- Absolute tense: a situation’s location in time relative to the moment of speech (past, present, future, timeless/unmarked)

'Tense' refers to the situation’s location in time: past, present, future, or timeless. These terms are actually a simplification, which is possible when the reference point is the time of speech:

- past = prior to speech time (anterior)

- present = simultaneous with speech time

- future = after speech time (posterior)

When a different reference point is used, it is more accurate to simply speak of time anterior, simultaneous, or posterior (if marked at all for location in time). When speech time is always assumed as the reference point, it is called absolute tense. When the reference point depends on context, it is called relative tense.

Hebrew has a combination of absolute tense and relative tense. Precisely because the tenses can be relative, it is vital to know what the reference point is -- what reference point the relative tense is relative to. (This is the reason for including reference point movement, below.)

| Relative tense of event | Reference point | English label | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | Past | Pluperfect (past-in-the-past) | He had built the temple. |

| Anterior | Present | Present perfect (past-in-the-present) | He has built the temple. |

| Anterior | Future | Future perfect (past-in-the-future) | He will have built the temple. |

| Simultaneous | Past | Past habitual (present-in-the-past) | He would build temples. |

| Simultaneous | Present | Present habitual (present-in-the-present) | He builds temples. |

| Simultaneous | Future | Future habitual (present-in-the-future) | He will build temples. |

| Posterior | Past | (future-in-the-past) | He was going to build a temple. |

| Posterior | Present | (future-in-the-present) | He will/is going to build a temple. |

| Posterior | Future | (future-in-the-future) | He will be going to build a temple. |

Aspect

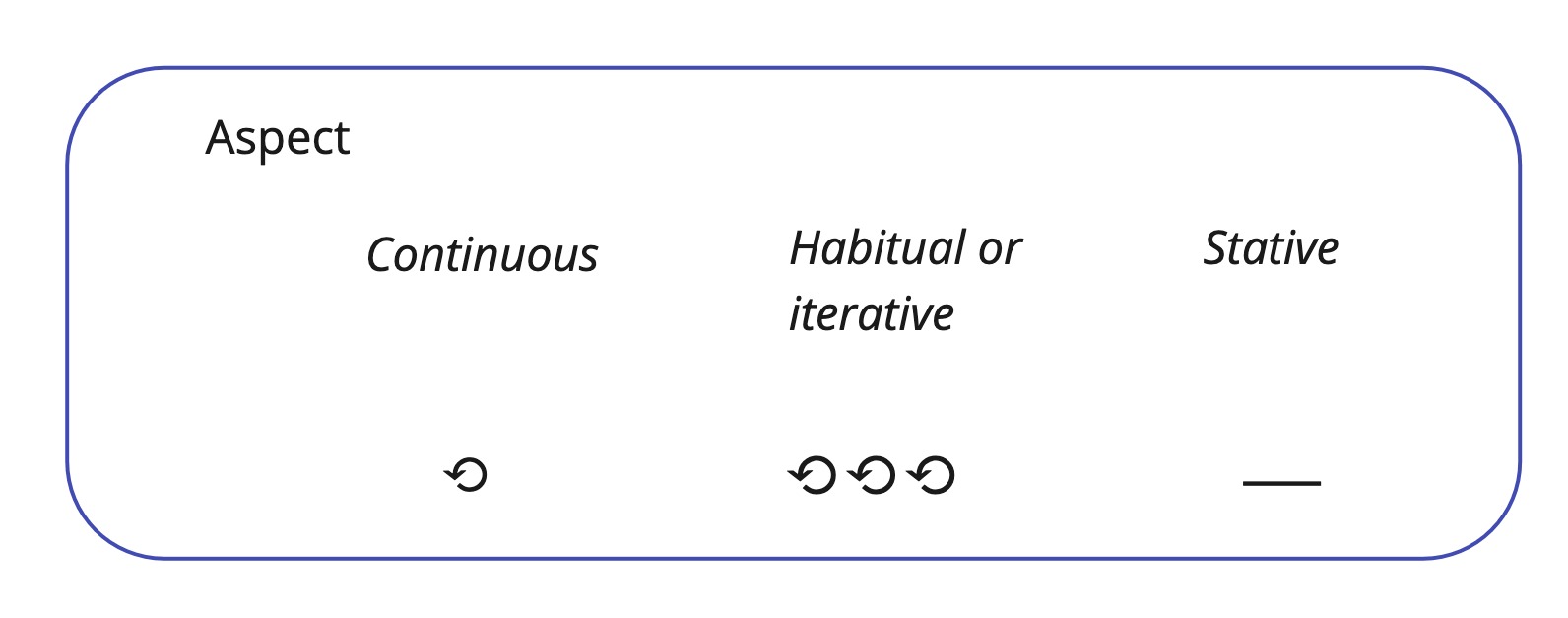

- Aspect: the 'temporal constituency' of a situation as portrayed (e.g. stative, continuous, or repeating)

Tense and aspect are conventional analytical categories, with situation aspect increasingly well established (particularly in its more limited form, lexical aspect). A former iteration of our verbal semantics tracked situation aspect for each verb, but it was not clear that the effort required had sufficient exegetical payoff. This version of verbal semantics does not track situation aspect. Instead, it tracks a more generic aspect that mostly coincides with viewpoint aspect in its more specific imperfective manifestations (continuous vs characteristic vs stative).

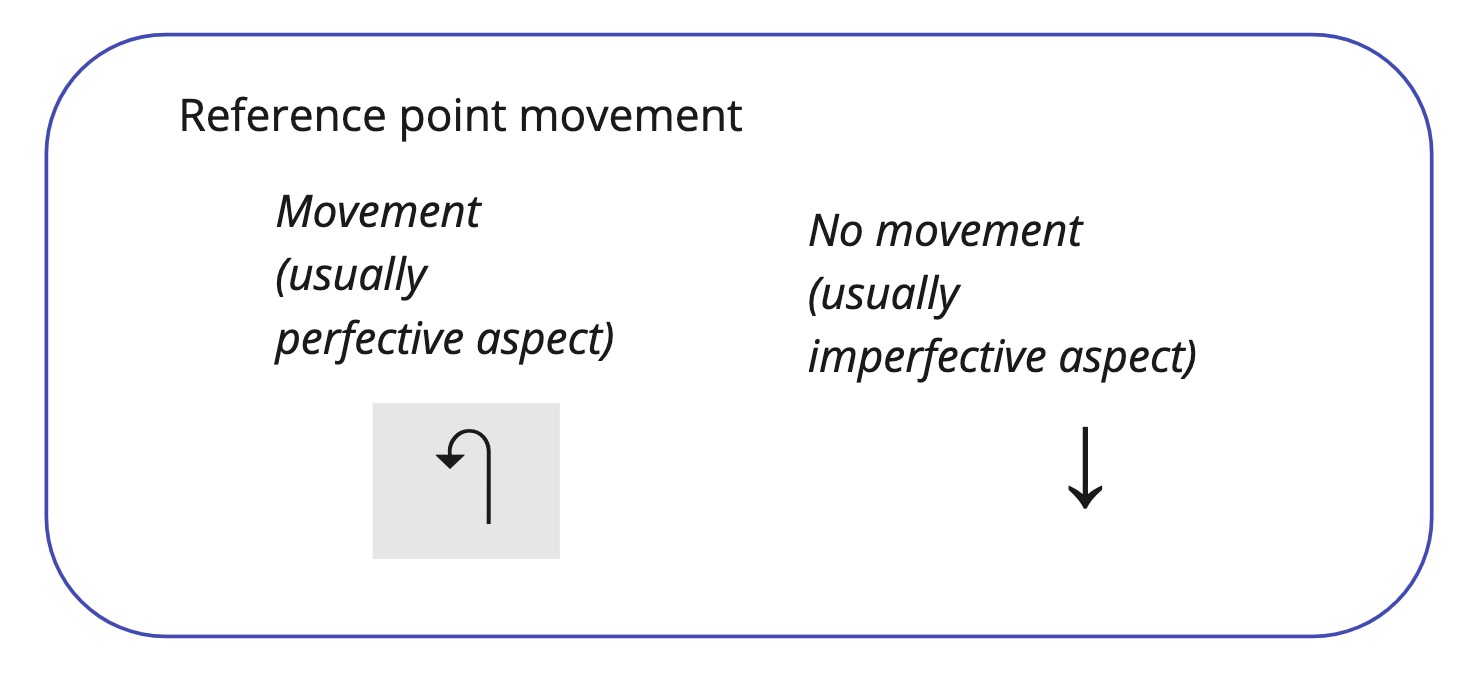

Reference point movement

- Reference point movement: whether or not the expected reference point in this discourse is updated after a situation, stereotypically tracking with perfective (movement) vs imperfective (no movement)

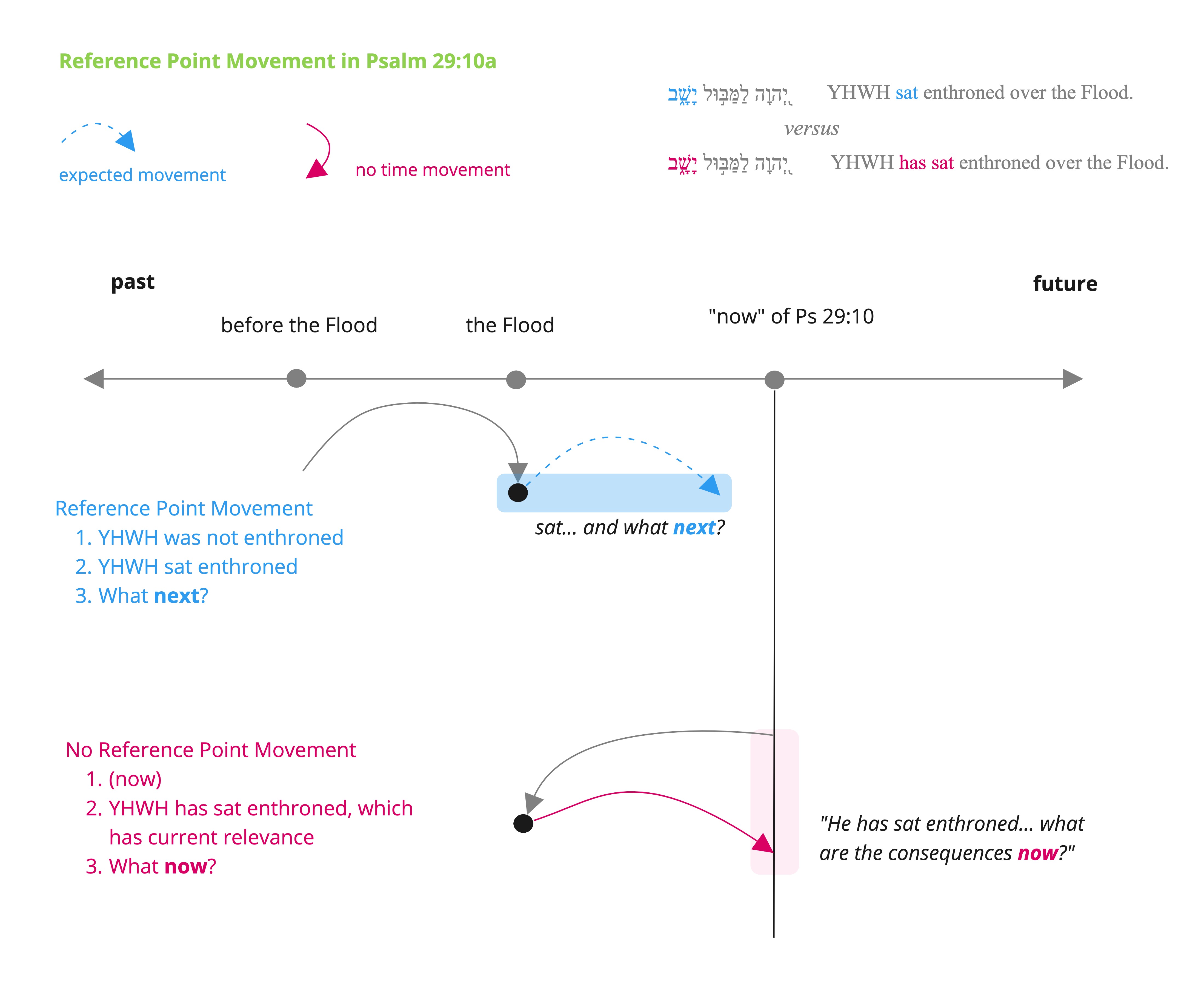

The category of reference point movement is exploratory. It holds the potential to explain the difference in English translation of Hebrew verbs, as a category that Hebrew does not distinguish but English does. The below diagram illustrates how reference point movement distinguishes between an English simple past and present perfect, as well as between an English future or imperfective present. Hebrew distinguishes neither of these pairs.

The nature of an ongoing text is that there is always a reference point for the next expected situation. With each new situation, the reference point may or not be updated. It is the expectation of reference point movement that matters here. The default for a narrative backbone is that the reference point advances with each action, leading the reader to expect What comes next? The default for a descriptive or non-narrative text is that the reference point not advance, because not chronology but some kind of logic drives the text. The reader expects, then, What are the consequences now? of the most recent situation described. These two options are demonstrated below for Psalm 29:10. The essential point is that this category explains the need to distinguish between forms in English where no such distinction is needed in Hebrew.

- Modality: the effective modality as would need to be translated into English (e.g. imperative, jussive, subjunctive, conditional, wish)

Imperatives, jussives and cohortatives are volitional modals, by morphology[1]. We-qatal and we-yiqtol are often also purpose/result modals. Clause-initial yiqtol, if in an a-line, should be presumed purpose/result modal unless proven otherwise.

Other forms of modality, such as wish, possibility, permission, conditionals and some purpose are often indicated by discourse markers, such as לו, אולי, פן, בעבר, etc. This kind of modality will be expressed morphologically in English and many other languages, and therefore we will track it, noting how it is marked in Hebrew by means other than morphology.

Steps

Before you begin...

- Copy the verbal semantics template and paste it onto your MIRO board.

- Copy the verbal semantics legend and paste it onto your MIRO board.

- Copy and paste the English and Hebrew texts in the relevant text boxes.

Overview:

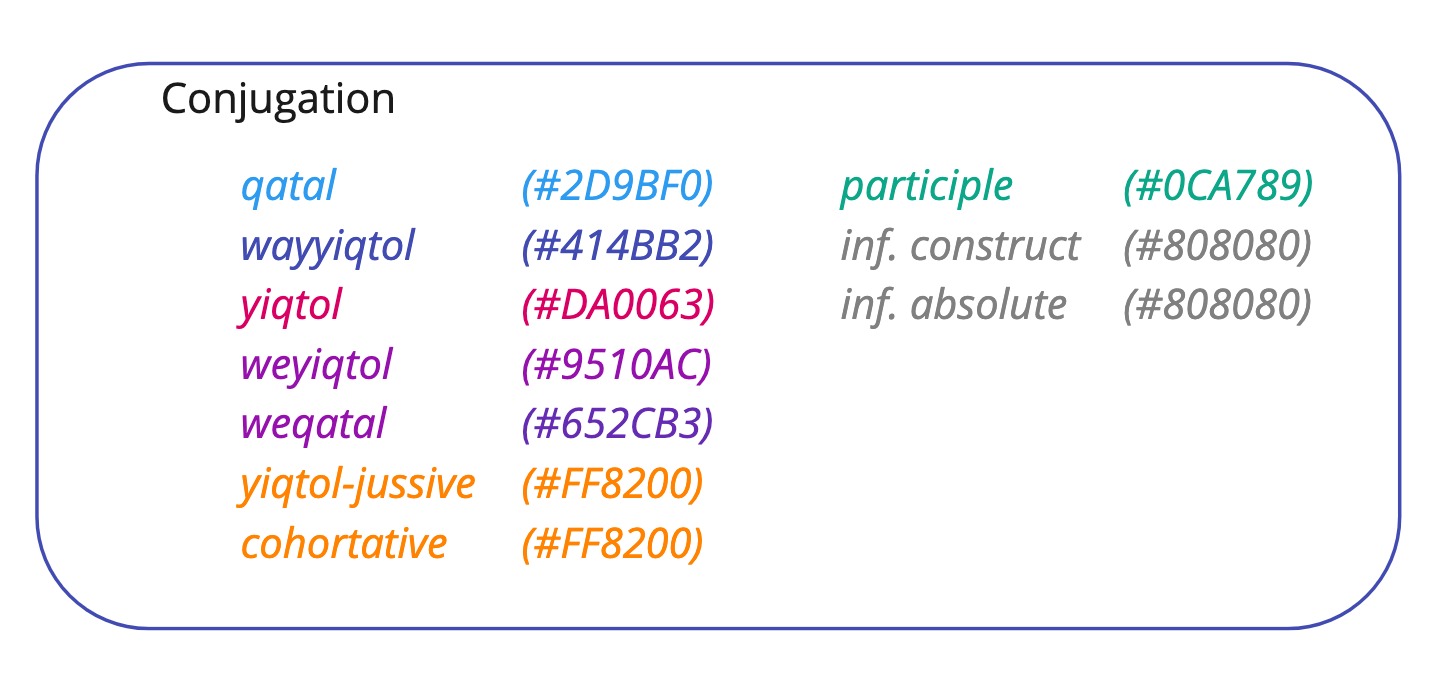

- Split the Hebrew text into lines according to verbal instances. Colour the Hebrew verbs (in the second column) according to morphology.

- Identify the verb's root, stem, conjugation, person/gender/number, and any suffix.

- Identify the verb's relative tense (e.g. yiqtol=posterior, qatal=anterior) and absolute tense (nearly always present) and place the appropriate arrow for the relative tense into the appropriate Fut/Pres/Past column.

- Identify any nuance of modality (specifically continuous, iterative/habitual or stative).

- Determine the expected movement of the reference point for each clause.

- Specify the effective modality of every finite verb. Specify the reason for the chosen modality.

- Make the verbal gloss in the Close-but-Clear bold and coloured according to effective verbal semantics (so waw-conjoined forms will merge with their governing verbs and ambiguous yiqtols will be coloured for either any semantics they effectively have).

1. Lay out the Hebrew text

Copy the table from the verbal semantics template and lay out the Hebrew text in the second column (one clause per verb, whether finite, infinitive or participial). Use OSHB for the Hebrew text. You should also be able to find it on the forum.

2. Morphology

Identify in the table the root, stem, conjugation, person/gender/number and suffix of every verb. If there are multiple options, duplicate the row and colour the background of the non-preferred row grey.

These should be relatively uncontested entries.

Following the template, colour the text of the Hebrew of each verb according to its morphological conjugation (e.g. qatal light blue, wayyiqtol dark blue).

3. Time

Tense

Identify both the relative tense (anterior, simultaneous or posterior, if tensed at all) and the absolute tense (future, present or past, if tensed at all). In the absolute tense column (usually 'Pres.'), put the arrow appropriate to the relative tense. Colour the arrow according to the conjugation.

If tense is not applicable to the verbal form (as with many participles and nominal clauses), leave the columns blank.

Aspect

The Aspect column is for tracking nuances of aspect. We begin with tracking continuous (ongoing action at the time of the reference point), habitual or iterative (starting and stopping and resuming regularly) or stative (no change) aspect. We may track more aspects as we find them exegetically significant.

Place the appropriate character in the Aspect column. Note that these are not images but actual characters. (Images make working with MIRO tables difficult. Everything in this table will be an actual character.)

| Continuous | ⟲ |

|---|---|

| Habitual or iterative | ⟲⟲⟲ |

| Stative | ⎯ |

Expected movement of the reference point

| Expected movement | ↶ |

|---|---|

| No expected movement | ↓ |

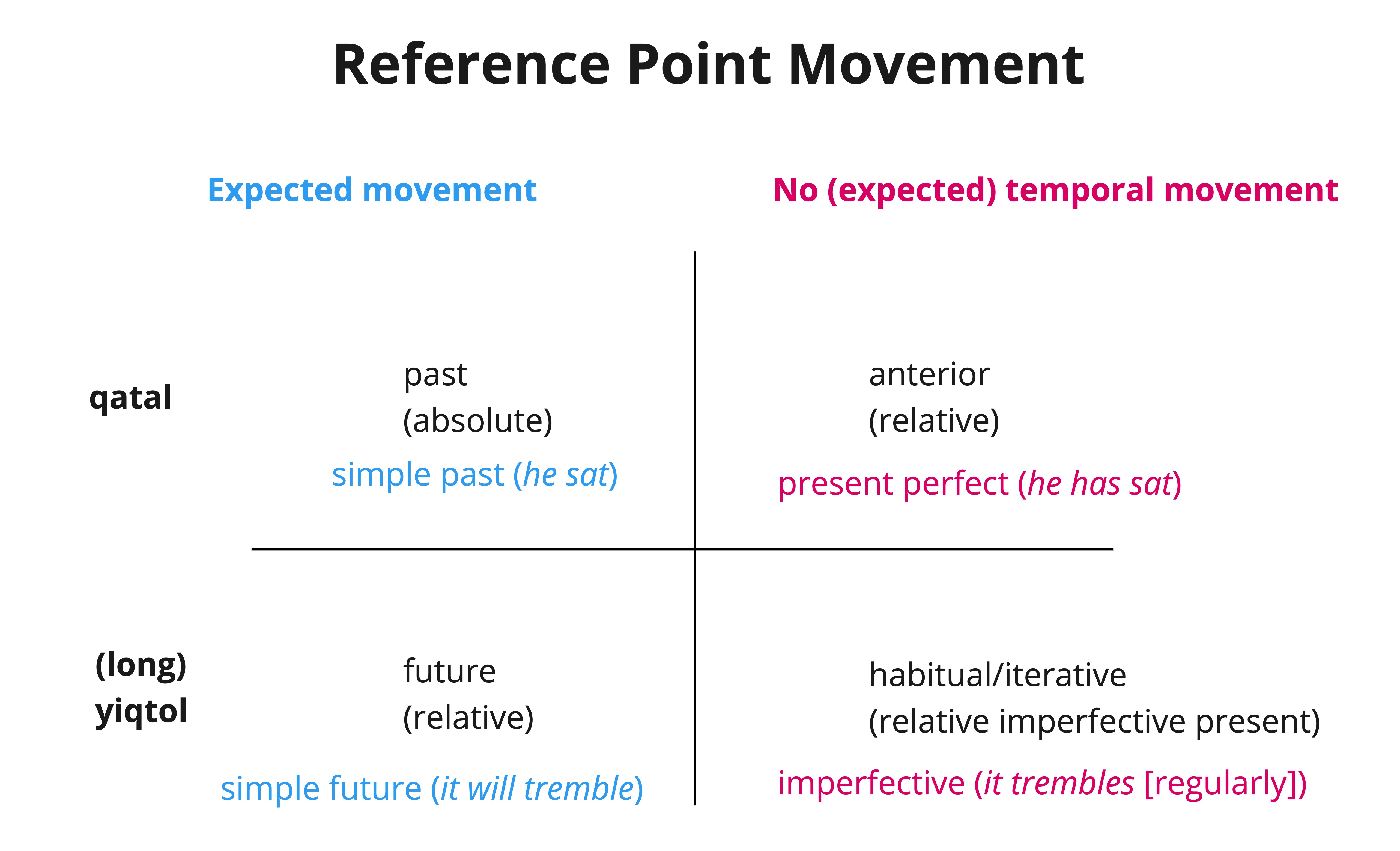

This simple diagram simplifies the indicative Hebrew verbal system along two axes, showing how the reference point movement dictates translation into English. Biblical Hebrew has a combination of absolute tense (qatal as a preterite) and relative tense (yiqtol and qatal as a perfect). Biblical Hebrew can happily combine these because it is not concerned with reference point movement, which is critical for understanding relative tense. (See below on Tense.)

English (and many other languages), however, makes a distinction, requiring a verb form that includes in its semantics the expectation of reference point movement. The difference between a preterite ('he ran') and a perfect ('he has run') is reference point movement: after 'he ran', we expect an updated (temporal) reference point: 'and what next?' After 'he has run', however, we expect an updated logical reference point: 'and so what?' The temporal reference point is unaffected, however: it is unchanged.

Much scholarly ink has been spilt, trying to account for the difference between the preterite and the perfect. This is our current proposal for the simplest yet linguistically adequate account for how they overlap (identical semantics of the event itself) yet differ (in expectations for the rest of the discourse).

The same distinction also, happily, explains the difference between yiqtol as future and yiqtol as imperfective present.

In sum, reference point movement is not a necessary feature of Biblical Hebrew on its own terms, but it is a crucial feature for translating Biblical Hebrew into many other languages, especially English.

5. Tense

6. Modality

Imperatives and jussives are volitional modals, by morphology. We-qatal and we-yiqtol are often also purpose/result modals. Clause-initial yiqtol, if in an a-line, should be presumed purpose/result modal unless proven otherwise.

Other forms of modality, such as wish, possibility, permission, conditionals and some purpose are often indicated by discourse markers, such as לו, אולי, פן, בעבר, etc. This kind of modality we have not yet officially addressed (but need to).

7. Translation

Translation is a combination of morphology, reference point movement, tense and the actual reference point. When the actual reference point changes (because time passes within the psalm), add an extra line in the table to indicate there is a new reference point. All these factors go into the translation gloss for the verb.

In the Verbal Semantics chart, include an Elaborative Paraphrase that makes as explicit as possible the verbal semantics. Exaggerated forms are acceptable for the sake of clarity.

This table provides a sample of model renderings, though without fully taking into account relative tense.

On the grammatical diagram, update the verbal glosses to those intended for the CBC.

8. Prepare for Live Review

Submit your draft for written review.

After completing a full draft according to the guidelines above, find your visualisation's "task" in ClickUp and update its status to "under review." Assign the task to the layer overseer, who will provide written review notes on Miro. Note: you may also create a ClickUp “subtask” for review, and assign the subtask to the layer overseer. Either way, make sure to update the main task status to “under review.”

Make revisions.

Based on the written feedback provided on Miro by the layer overseer on Miro, revise your draft and complete any remaining research needed. Update the ClickUp task to reflect its status (as in #1 above). More than one round of revisions may be necessary. The visualisation should be as polished as possible (content and formatting) before its Live Review.

Identify issues that need Live Review.

After revising your draft in dialogue with the layer overseer, list any remaining questions or issues that require group expertise or discussion. Important: this short list should be limited to issues that you and the layer overseer were unable to resolve. Before the Live Review, type these questions in a Miro text box (titled "Live Review Issues" above the visualisation to be reviewed. This will help ensure that the Live Review effectively addresses the most important issues.

Attend Live Review.

The goal of the Live Review is to make any remaining revisions and approve the visualisation(s). If the group determines that further work is needed, then this should be done in dialogue with the layer overseer.

9. Revise and send for final checks.

Make final revisions.

After the Live Review, make any remaining revisions as promptly as possible. Contact the layer overseer if you have questions.

Send for final checks.

In ClickUp, change the task status to “ready for final checks.” Make sure to assign the task to the layer overseer, so that they are notified. The layer overseer will take care of final checks and publication.

Bibliography

Cook, John. “Actionality (Aktionsart): Pre-Modern Hebrew.” In Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. Edited by Geoffrey Khan. Consulted online on 22 September 2021 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2212-4241_ehll_EHLL_COM_00000203>.

Fleischman, Suzanne. Tense and Narrativity: From Medieval Performance to Modern Fiction. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010. PDF here.

Gentry, Peter. “The System of the Finite Verb in Classical Biblical Hebrew.” Hebrew Studies 39 (1998): 7–39. Link here.

Hornkohl, Aaron. “Biblical Hebrew Tense–Aspect–Mood, Word Order and Pragmatics: Some Observations on Recent Approaches.” Open-access version here.

Hovav, Malka. “Lexicalized meaning and the internal temporal structure of events.” Pages 13–42 in S. Rothstein (ed.), Theoretical and Crosslinguistic Approaches to the Semantics of Aspect. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2008. Available as PDF here.

Kroeger, Paul. Analyzing Meaning: An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics. Textbooks in Language Sciences 5. Berlin: Language Science Press, 2018. Part VI, “Tense & aspect” (pp. 377–446). This title can be downloaded here.

Levin, Beth. “Lexical Semantics of Verbs” course handouts. UC Berkeley, 2009. Course Page here. See especially “Lecture 4: Aspectual Approaches to Lexical Semantic Representation” (link). Cf. also Levin’s paper “Verb Classes within and across Languages,” 2013. (link)

McIntyre, Andrew. “Tense, Aspect and Situation Type."

Nadathur, Prerna. “Lexical Semantics” course handouts. Institut für Sprache und Information Heinrich Heine Universität, 2019–20. Course page here. See especially “Week 11: Aspect and aspectual classes I” (link).

“Tense, Aspect, and Modality with Nora Boneh (Part 1 of the Verbal Systems of the Biblical Languages series). The Biblical Languages Podcast. Biblingo, 2021. Link here.

Vendler, Z. “Verbs and Time.” Pages 97–121, Chapter 4 of Linguistics in Philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967. Link here.

Glossary

For terms not included here, please see SIL’s “Glossary of Linguistic Terms.”

Accomplishment: a situation type in which the event happens over time (durative), but does have a natural endpoint (telic). Unlike semelfactives (e.g. blink), accomplishments involve a change, e.g. run a mile; build a house.

Achievement: a situation type in which the event does not happen over time (punctual), but does have a result state. Achievements occur at a single moment, e.g. reached the top; find; win.

Activity: a situation type in which the event happens over time (durative), but doesn’t have a natural endpoint (atelic).

Aspect: a grammatical category which refers broadly to the relationship between a situation and time; cf. situation type; viewpoint aspect.

Atelic: see telicity.

Durativity: This aspectual property asks if the situation starts and stops. A durative situation extends over time (includes states, resultant states, and continuous action). E.g., She was swimming. A punctual situation is presented as happening instantaneously (includes repetitive actions). E.g., He kicked the ball (single), or He was kicking the ball (repetitive).

Phasal aspect:

Punctual: see durativity.

Semelfactive: a situation type in which the event is punctual, but without any resultant state.

Situation type: sometimes referred to as Aktionsart or situation aspect. The most basic distinction is between state and event. A state is a situation characterised by durativity and lack of change, e.g. possessing, desiring, loving, ruling, believing. An event is a situation in which something “happens,” e.g. eating, listening, teaching. An event may be one of four different situation types, see accomplishment; achievement; activity; semelfactive.

Telicity: the property of a situation which indicates whether or not the situation has a natural end point; a situation is either telic or atelic.

Tense: refers to a situation’s location in time.

Viewpoint aspect: sometimes referred to simply as aspect. The traditional distinction in viewpoint aspect is between perfective and imperfective aspect. This category is concerned with how the situation is represented, not its inherent properties. See perfective; imperfective.

- ↑ The cohortative morphology becomes the standard 1cs morphology for wayyiqtol forms in Late Biblical Hebrew