User's Guide: Macrosyntax

User's Guide Contents

Macrosyntax

Syntax looks at how words are arranged to form sentences. Macrosyntax goes further - it looks at how clauses work together to shape the flow of meaning across a whole passage. It helps us trace how information is introduced, developed, and highlighted—how the author moves the reader from what’s known to what’s new.

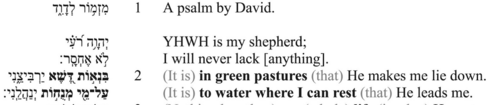

Take for example Psalm 23:2.

| Text (Hebrew) | Verse | Text (CBC) The Close-but-clear translation (CBC) exists to provide a window into the Hebrew text according to how we understand its syntax and word-to-phrase-level semantics. It is designed to be "close" to the Hebrew, while still being "clear." Specifically, the CBC encapsulates and reflects the following layers of analysis: grammar, lexical semantics, phrase-level semantics, and verbal semantics. It does not reflect our analysis of the discourse or of poetics. It is not intended to be used as a stand-alone translation or base text, but as a supplement to Layer-by-Layer materials to help users make full use of these resources. |

|---|---|---|

בִּנְא֣וֹת דֶּ֭שֶׁא יַרְבִּיצֵ֑נִי

|

2a | He makes me lie down in green pastures.

|

עַל־מֵ֖י מְנֻח֣וֹת יְנַהֲלֵֽנִי׃

|

2b | He leads me to water where I can rest.

|

There are two ways we can read this verse, depending on where the primary focusI.e., the new/important information is:

- If the primary focus is on the shepherding activities of making me lie down and leading me, then that is the main informational contribution of the sentence and the rest is presupposed.

- If the primary focus is on the green pastures and water where I can rest, then the shepherding activities are presupposed and the primary contribution of the sentence is to communicate the good nature of that shepherding by where and how YHWH acts as shepherd.

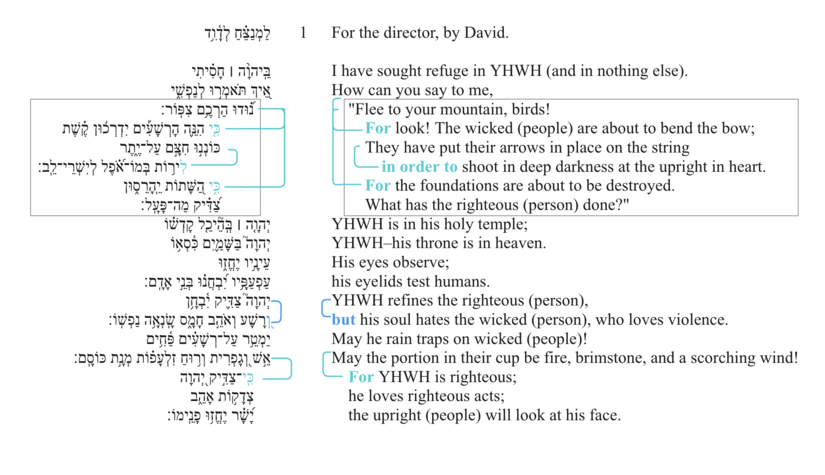

Macrosyntax Diagram

Legend

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[1] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[2] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

We answer these kinds of questions, and much more, in our Macrosyntax Diagram.

Here you can see text laid out clause by clause, with the Hebrew on the left and the CBC on the right. In this layer, however, the CBC has been expanded to draw out important information. As you can see here, “in green pastures” and “water where I can rest” are in bold. This is because in Hebrew these words are in focus; they are positioned at the beginning to indicate their role as the primary contribution of the sentencePrimary contribution usually, but not always, overlaps with "new" information..

In v. 1 the shepherd image has already been presented, so in v. 2 him “leading me” and “making me lie down” is already presupposed, assumed. But what’s new is where he makes me lie down. Not in the desert sand or rocks, but, as made clear in the Diagram: “(It is) in green pastures (that) he makes me lie down. (It is) to water where I can rest (that) he leads me”.

In this macrosyntax visual we present all the important parts of the “discourse structure” of the text, the way the text moves from what’s known to what’s new. We use colours, connecting lines, and other symbols to show things like vocatives, subordination and coordination, topic and focus, and more. Everything is explained in the Legend, which can be found just above the diagram.

Key Features of the Diagram

- Clause per Line: The text is arranged into one clause per line, based on our analysis in the grammatical diagram.

- Divisions: The text is divided into discourse units based on discontinuities and transitions in the text. As you can see in for Psalm 23 the text is divided into two main units: vv. 1b-5, and then the separate closing statement in v. 6. See the “Divisions” tab below for more details.

- Coordination and Subordination: Subordinated clauses are indented. When conjunctions appear, these are displayed in teal for subordinating conjunctions and blue for coordinating conjunctions.

- Vocatives and Discourse Markers: Vocatives and discourse markers are identified and colored. For more on these important features see the tabs below.

- Word Order / Topic and Focus: The word order of every clause is analysed, and all topic and focus features are presented. For more on these important features see the Word Order tab below.

- CBC Expansion: Where helpful the text is expanded with (grey text in parentheses), to show clearly the insights from macrosyntax analysis.

Beneath the diagram is the Notes section. This includes analysis and explanations of the divisions, word order, vocatives, discourse markers, and conjunctions. Click on the tabs below to read more about each of these topics.

Divisions

In this section we discuss the division of the text into discourse units. The divisions here are based specifically on elements of macrosyntax, and not on semantics. Examples of elements creating divisions in the text include:

- discourse markers (such as the selah in Ps 24:6 and 10 or the כִּי in Ps 91:3, 9 and 14)

- topic shifting with overt pronouns (such as וְאַתָּה in Ps 22:4 and 20)

- direct speech (e.g., Ps 68:23-24)

- patterns of coordination (e.g., Ps 20) & subordination (e.g., Ps 118:1-4)

- distinct predication types, such as exclamatives (e.g., Ps 31:20)

Topic and Focus

Every sentence is made up of two kinds of information:

- Topic: What is known, familiar, or recognizable to the audience.

- Focus: The new, important, or highlighted information.

Consider the answer to the question:

- What did John eat? | John ate bread.

The fact that John ate is the topic, what is already known, familiar, or assumed. The focus (the new, important, and highlighted information) is specifically what John ate, namely bread.

The focus of a sentence can come in three ways or structures:

1. Predicate Focus: The default focus structure is that the predicate is the focus, and the subject is the topic.

- What did John do? | John ate bread.

2. Constituent Focus: The second focus structure is constituent focus, where only one specific element of the sentence is new or important (focus), and the rest is assumed (topic).

- What did John eat? | John ate bread.

- Who ate bread? | John ate bread.

3. Sentence Focus: Sometimes the whole sentence can be in the focus. This structure, also known as a thetic sentence, treats the entire clause as new information. Consider these examples of thetic sentences:

- It's raining.

- My head hurts.

- Someone's at the door.

Word Order

In Biblical Hebrew, the normal (or default) word order is verb–subject–object (VSO). Sometimes this order is changed and an element of the sentence is moved to the beginning of the sentence to give it special emphasis or highlight it for the listener.

This movement to the front is called fronting. When a word or phrase is fronted, it becomes marked, meaning it stands out from the normal flow of information. Writers or speakers can use fronting to draw attention to that element, often with a specific function. Both topic and focus can be marked.

Our Macrosyntax resources identify these cases and how they contribute to the flow of information in the text. In the notes on Word Order you will explanations of cases of marked word order and the specific function in context. For how we visualize marked topic or focus in the diagram, see the legend below:

Legend

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[3] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[4] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Vocatives

Many psalms contain vocatives-words or phrases of direct address (e.g. "O God", "O my soul"). These vocatives directly name the addressee, and can also have wider poetic, pragmatic, and rhetorical functions.

We analyze the function of each vocative, case by case, considering, for example:

- Whether the vocative signals a shift or continuation of the addressee.

- Common functions for vocatives at the beginning of a clause, like identifying the addressee or signaling a shift in a conversation (Kim 2022, 213-217).

- Common functions for vocatives at the end of a clause, like signaling the end of a conversational turn (Kim 2022, 217-222).

- Common functions for vocatives in the middle of a clause (Kim 2022, 222-238).

Selected Bibliography:

Two sources that especially inform our analysis are:

- Kim, Young Bok. 2022. Hebrew Forms of Address: A Sociolinguistic Analysis. Phd diss., UNiversity of Chicago. Available here.

- Miller, Cynthia L. 2010. “Vocative Syntax in Biblical Hebrew Prose and Poetry: A Preliminary Analysis.” Journal of Semitic Studies, vol. 55, no. 2: 347-364.

Discourse Markers

Discourse markers are "meta-level" words that “signal the speaker’s view/attitude/judgement with respect to the relationship between chunks of discourse that precede and follow it, typically in the sentence (utterance)-initial position.”Onodera 2011:615

- Suggested resource: Each of these discourse markers and their common functions are listed in BHRG §40.1 Discourse Markers. This resource is often the starting point for our analysis.

The following words are generally recognized as discourse markers in Biblical Hebrew, and we analyze each occurrence within its specific context:

אוֹ | or אוּלַי | perhaps, maybe אוּלָם | however, indeed אֲזַי/אָז | then אֵין | there is not אַךְ | surely, only, nevertheless אָכֵן | surely, truly אַל | do not אִם | if, whether אָמְנָה | truly, indeed אָמְנָם/אֻמְנָם | truly, indeed אַף | also, even אֶ֫פֶס | except, nevertheless בַּל | not בְּלִי | without בִּלְתִּי | except, without בַּעֲבוּר | for the sake of, because גַּם | also, even הֵן | behold, indeed הִנֵּה | look!, behold ו | and, but, now וְהָיָה | and it shall be וַיְהִי | and it happened טֶ֫רֶם | before יֵשׁ | there is כֹּה | thus, so כִּי | for, because, that, when כֵּן | so, thus לֹא | not לְבַד | alone, only לוּ | if only, would that לוּלֵי | if not, unless לָכֵן | therefore לְמַ֫עַן | in order that, for the sake of עוֹד | still, again, yet עַל־כֵּן | therefore עַתָּה and וְעַתָּה | now' פֶּן | lest רַק | only, but, surely

Conjunctions

In this layer, we distinguish between coordinating and subordinating conjunctions. As noted above, conjunctions are color-coded as teal for subordinating conjunctions and blue for coordinating conjunctions. Syntactically subordinated clauses are indented.

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.