User's Guide: Poetic Structure

User's Guide Contents

Poetic Structure

Introduction

To understand poetic analysis, consider the difference between going for a hike in nature with and without a map. If you don’t have a map, you might enjoy the beauty all around you for some time, but eventually you get lost and disoriented.

When it comes to the Psalms, we must remember that they are not just random collections of beautiful lines, like this:

Instead, they are intricately crafted journeys, with rising tension, turning points, climaxes, and all kinds of rhythms and patterns, just as a perfect hike in nature has steep climbs, shaded valleys, peaks and viewpoints, and places to rest. In the Psalms every single word is carefully positioned right where it is. But if you don’t have a map guiding you through, you might end up feeling lost and end up missing the beauty of the psalm as a whole. Our poetic analysis provides you with that map.

There are five parts to our poetics resources:

- At-a-Glance Visual: Simplest overview of psalm’s structure

- Poetic Macrostructure: Detailed overview of poetic structure

- Line divisions: Poetic lines of the psalm

- Poetic Features: The artistry and poetic design of the psalm

- Prominence: What 'stands out' in the psalm

For full explanation of the At-A-Glance Visual, see the Overview page. This page focuses primarily on Poetic Macrostructure and Line Divisions. For information on Poetic Features, see here, and for Prominence, see here.

At-a-Glance + Poetic Macro-structure

The Macrostructure tab has two parts: an expandable view of the At-a-Glance visualClick the At-a-Glance button to expand. and the detailed visual of the poetic macrostructure.

These two visuals correspond closely to each other, with the At-a-Glance providing a simple overview and the poetic macrostructure providing a detailed and comprehensive view.

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Sections and Sub-sections

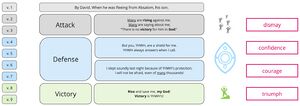

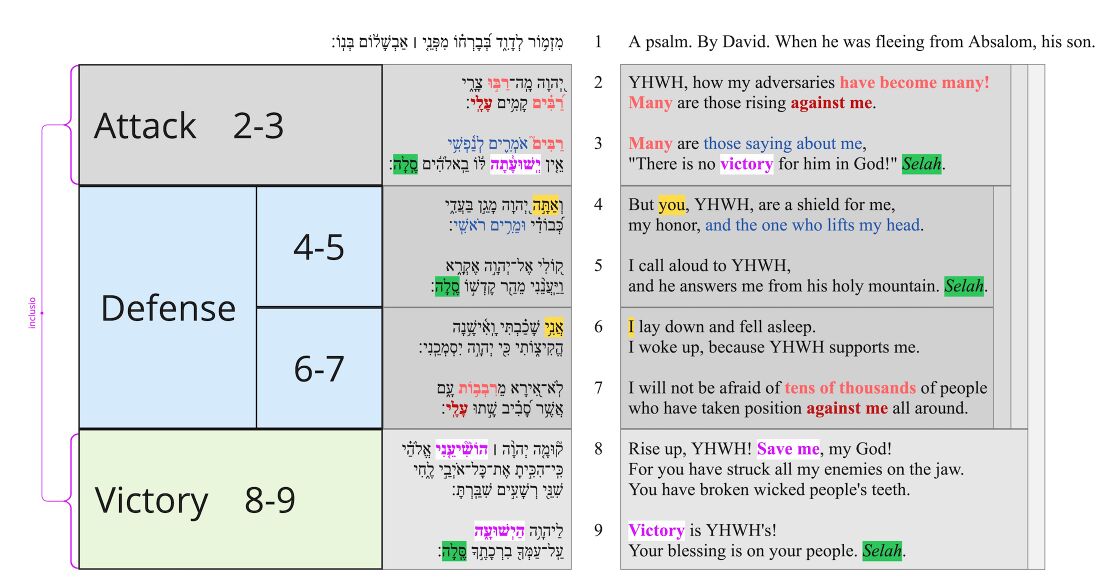

All the different features of the At-a-Glance visual are presented and explained in the Structure part of the Overview page. What is important to focus on here is the arrangement into sections and sub-sections. Take for example the At-a-Glance for Psalm 3. You can see here the three main sections (1-3 Attack | 4-7 Defense | 8-9 Victory), with the middle section Attack divided into two subsections (4-5 | 6-7).

Poetic Macrostructure

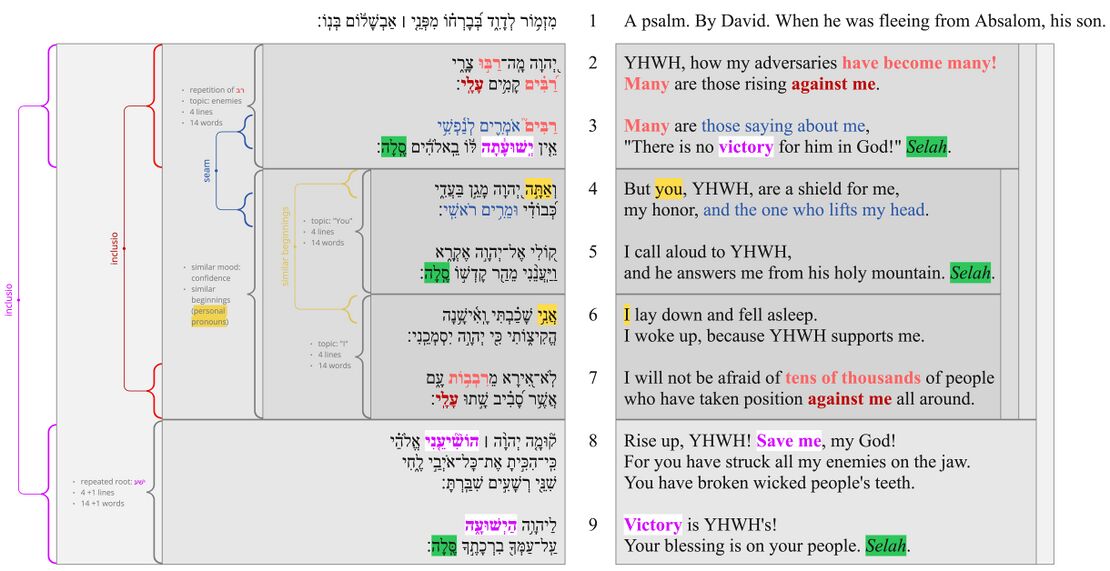

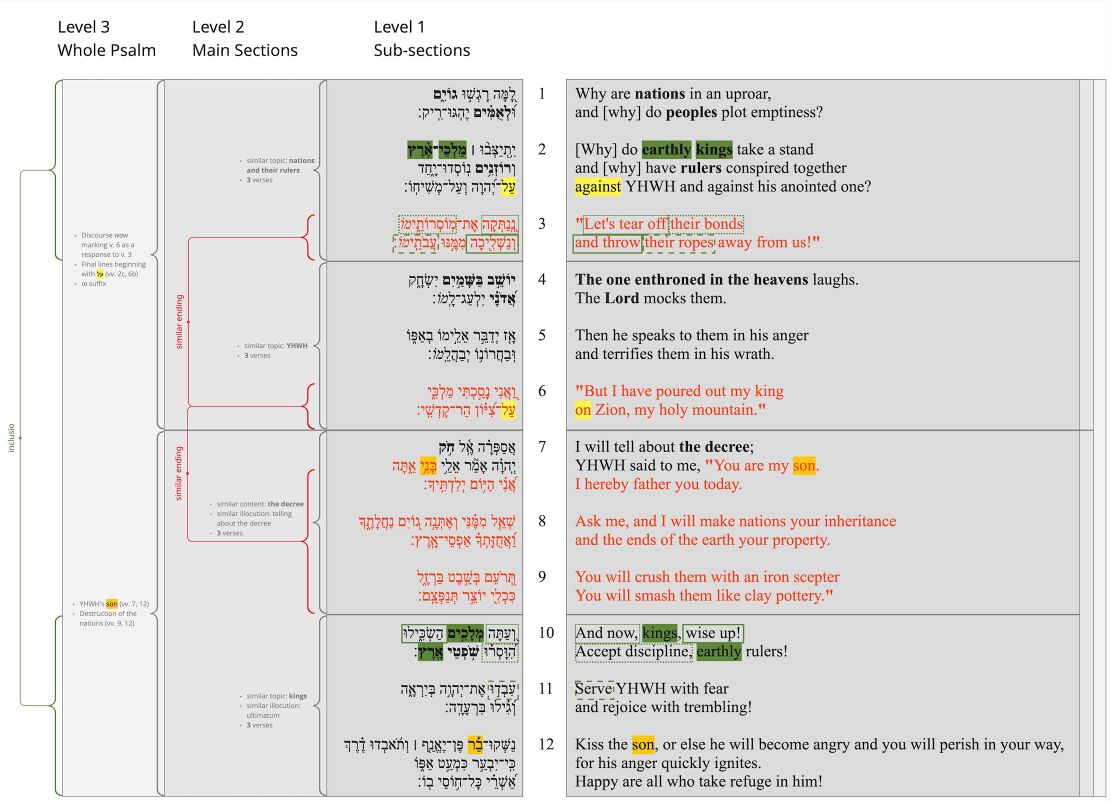

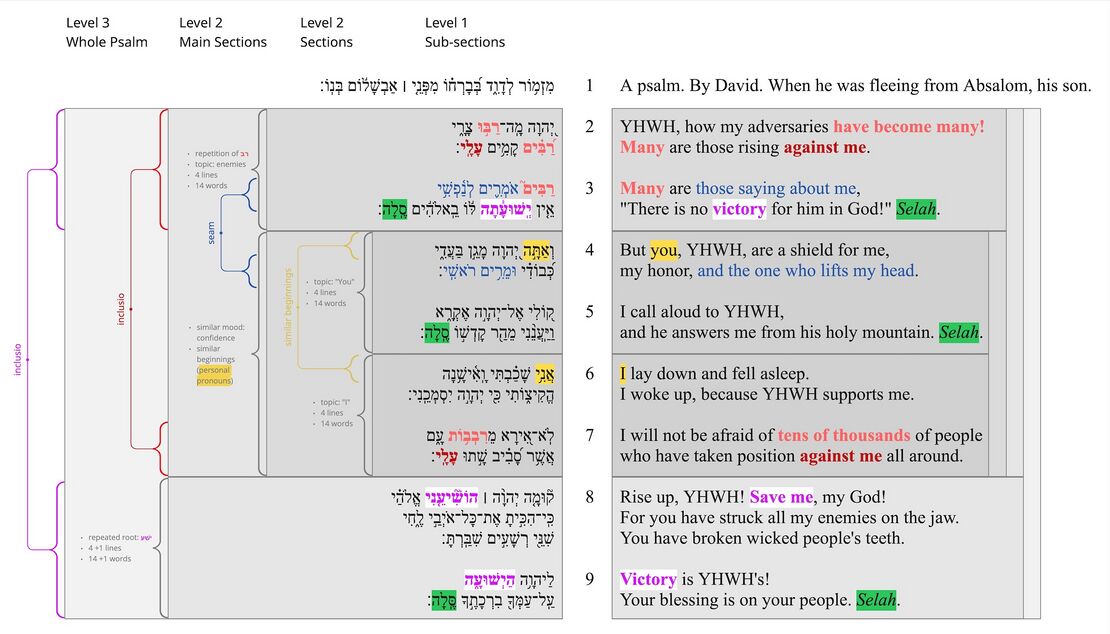

The sections in the At-a-Glance overview correspond closely (but not always exactly) to the sections and subsections in the detailed poetic macrostructure visual, which looks like this:

This visual may look overwhelming at first. This is why it is helpful to start with the sections in the At-a-Glance visual. You can see they correspond to the Macrostructure as follows:

In this poetic macrostructure we map out the complete poetic structure of the psalm, in all of its detail. This analysis is based on two main ideas:

Hierarchy: Psalms can be viewed in the following hierarchy, from the smallest unit to the largest:

- LinesAlso known as colon, hemistich, half-line, verset.: the basic building block of Hebrew poetry.

- VersesAlso known as line group, strophe, bicolon/tricolon, couplet.: Small grouping of lines, usually two or three.

- Sub-sectionsAlso known as strophe, stanza, canticle, canto.: Smaller groupings of verses, embedded within higher-level sections.

- Main sectionsAlso known as strophe, stanza, canticle, canto.: Larger groupings of verses.

Structure and Patterns: Psalms are full of detailed patterns, repetitions, breaks and connections. Careful analysis shows how each section and sub-section is bound together as a unit, and how each section relates to other sections in the psalm. Special focus is given, for example, to:

- Inclusios: A poetic frame where a section begins and ends with the same word or phrase, marking it as a unit.

- Chiasms: When multiple parts match each other in an inverted mirror pattern (e.g. AB|B'A' or ABCB'A').

- Repeated roots/words: Deliberate repetition of the same Hebrew root.

- Sound repetition: Deliberate repetition of similar sounds.

- Staircase devices: A pattern where a key word or phrase is repeated and expanded in the next part.

- Word-count: Deliberate patterns using specific numbers of words with symbolic meaning.

- Prominence: Using various poetic devices to make specific words, phrases, or sections stand out in a special way.

- And more!

For more detail on the Macrostructure visual, expand the explanation below.

Detailed Explanation

This section will go into a bit more detail with our poetic macrostructure, looking at (1) Sections Layout, (2) Sections Analysis, and (3) Features and Patterns.

Sections Layout

Each grey box represents a section or sub-section of the psalm. These sections are then arranged hierarchically, creating an overall map of the way the different parts of the psalm fit together. Sometimes this is simple and easy to visualize, and other psalms are more intricate and complex. Compare for example the poetic structures of Psalm 2 and Psalm 3:

Psalm 2 has a simple arrangement into three levels. Level 1, the most detailed, shows 4 equal sized sub-sections, with three verses each. These sub-sections are then arranged on level 2 into two halves, and then level 3 shows the psalm as a whole. Contrast this with Psalm 3, where we have 4 levels of hierarchy in the psalm’s structure.

In this psalm we have 4 clear sub-sections displayed in level 1. However, the two middle sections are also bound together as one larger section, for example with the similar beginnings of v. 4 and v. 6. This is displayed on level 2. Meanwhile level 3 shows that the psalm can also be understood as having two main parts, vv. 2-7 and vv. 8-9. This is displayed in level 3. Level 4 then shows the patterns binding the psalm together as a whole.

Sections Analysis

We present our analysis of these poetic sections using 4 tools:

- Highlights/Text Color: Key features in the text are highlighted or given a different font color. These can be features that appear within a section, binding that section together, or between sections, connecting different sections together.

- Bullet Points: Concise notes on the features highlighted in the text.

- Connecting Lines: Connecting lines to show different connected sections.

- Notes: The notes beneath the visual often include more detailed discussion of issues in poetic structure.

Notes

Beneath the visual are detailed notes explaining the reasoning for our understanding of the poetic structure. The views of other scholars are discussed and any special features or additional information is presented.

Line Divisions

When preparing our resources, Line Division analysis is the first step in our poetics layer and provides the foundation for the rest of our poetic analysis.

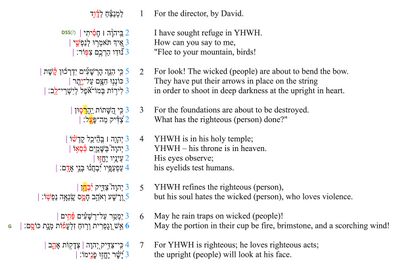

All scholars agree that Hebrew poetry is written in carefully arranged lines, usually with about 3-5 words each. Together these lines are arranged into verses. However, it is not always easy to know where to break up the lines. Take for example Psalm 11:5, and compare the NIV and NLT translations:

| NIV Psalm 11:5 | |

|---|---|

| יְהוָה֮ צַדִּ֪יק יִ֫בְחָ֥ן | "The LORD examines the righteous, |

| וְ֭רָשָׁע וְאֹהֵ֣ב חָמָ֑ס שָֽׂנְאָ֥ה נַפְשֽׁוֹ׃ | but the wicked, those who love violence, he hates with a passion." |

| NLT Psalm 11:5 | |

|---|---|

| יְהוָה֮ צַדִּ֪יק יִ֫בְחָ֥ן וְ֭רָשָׁע | "The LORD examines both the righteous and the wicked. |

| וְאֹהֵ֣ב חָמָ֑ס שָֽׂנְאָ֥ה נַפְשֽׁוֹ׃ | He hates those who love violence." |

Where one positions “the wicked” (וְרָשָׁע), at the end of the first line or the beginning of the second line, completely changes the meaning. Does YHWH examine the righteous in contrast to the wicked, or does he examine the righteous AND the wicked!? You can read our answer here!

To resolve these issues we consider six pieces of evidence:

| External Evidence | Internal Evidence |

|---|---|

| Pausal forms | Line length & balance |

| MT accents | Symmetry & parallelism |

| Manuscripts | Syntax |

Internal evidence, within the text itself, considers line length and balance, symmetry, parallelism, and syntax. External evidence considers the witness of traditions passing the text down through the ages. Within the main Jewish (Masoretic) tradition, we consider both pausal forms (special forms that often occur at the end of a line) and the Masoretic accents (the musical/cantillation system for synagogue readings). Beyond this, many manuscripts throughout history arrange the text into poetic lines, providing valuable evidence. Special focus is given to the Masoretic Manuscripts, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Septuagint.

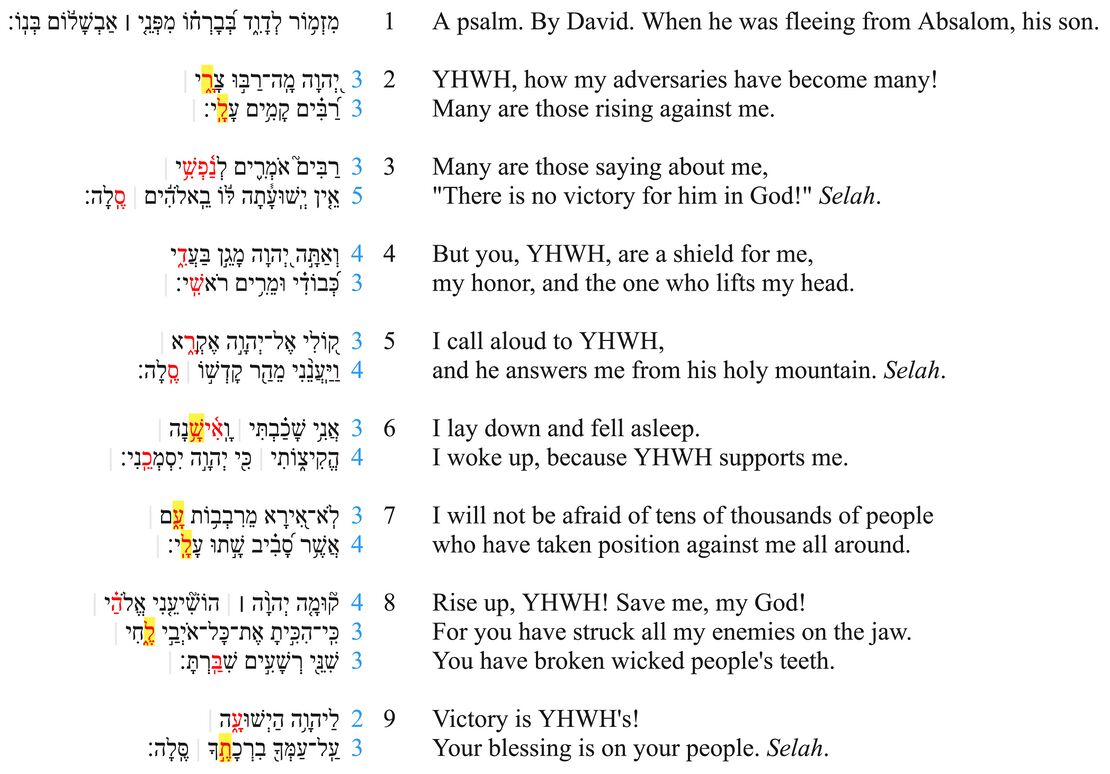

The line divisions visual for Psalm 3 looks like this:

Features of Line Division Visual

- Lines: All words are arranged into poetic lines.

- Word Count: To the right of each line, we list the number of words in the line.

- Verses: All poetic lines are arranged into verses.

- MT Accents: Accents connected to line divisionFor details on these accents see MT Accents and Line Division below. are displayed with red font.

- Pausal Forms: Pausal forms are highlighted in yellow.

- The light grey pipe | indicates a clause boundary.

- Disputes: When line division is uncertain, we note which manuscript tradition we follow using green font (DSS = Dead Sea Scrolls, G = Greek/Septuagint, MT = Masoretic Text).

Counting Prosodic Words

For this visual, we will define prosodic words in terms of the Masoretic tradition: any unit of text which is not divided by a space or which is joined by maqqef (or ole weyored) is a prosodic word.Krohn defines prosodic words as "i) unbound orthographic words that have at least one full syllable (CV, where V is not a shewa), or ii) orthographic words joined together by cliticization (Krohn 2021, 103). E.g., כִּ֤י הִנֵּ֪ה הָרְשָׁעִ֡ים יִדְרְכ֬וּן קֶ֗שֶׁת contains 5 prosodic words; צַ֝דִּ֗יק מַה־פָּעָֽל contains two prosodic words; etc. The relevance of counting prosodic words is two-fold:

- The length of lines typically ranges between 2 and 5 prosodic words.Cf. Krohn 2021, 103. According to Geller, “lines contain from two to six stresses, the great majority having three to five” (NPEPP 1998, 510). Hrushovski suggests a narrower range of two to four stresses (“Prosody, Hebrew,” 1961). It may be possible for a line to contain more than 5 prosodic words, though such a line division would require justification on other grounds. If a line has more than 5 prosodic words, then bold the number (e.g. 6).

- Lines also tend to be balanced in relation to one another. Symmetrically-arranged line pairs in particular tend not to differ by more than one prosodic word.Emmylou Grosser notes in her analysis of Judges 5 and the Balaam Oracles of Num. 23-24 that symmetrically-arranged line pairs tend to have “either equal stresses, or stresses unequal by one with balance of syllables deviating by no more than one” (Grosser “Symmetry” 2021). Given this tendency toward rhythmic balance, Geller concludes that “passages with such symmetry form an expectation in the reader’s mind that after a certain number of words a caesura or line break will occur… The unit so delimited is the line. So firm is the perceptual base that long clauses tend to be analyzed as two enjambed lines” (Geller, "Hebrew Prosody", NPEPP, 1998, 509-510). Lines within a line grouping may at times be imbalanced, but this division of the text must be justified on other grounds.

Note on Word-Count: The line division visual presents only prosodic word count. However, when we do our poetic analysis as a whole (i.e. poetic structure, poetic features, prominence) we often analyze word count both in terms of prosodic words (e.g. two words joined by maqqef = 1 prosodic word) and actual words. The merits and relationship between these two modes of counting is an ongoing discussion in our team.

MT Accents and Line Division

Masoretic accents which tend to correspond with line divisionsThe following analysis of the accents is based on Sanders and de Hoop, forthcoming §1.4.2. According to Sanders and de Hoop, the basic purpose of the accents is to guide the recitation of the text (see Sanders and de Hoop, "The System of Masoretic Accentuation: Some Introductory Issues") and not necessarily to mark poetic lines. Thus, the relationship between the accents and poetic line division is indirect. are indicated in red. These include the following six accents:

- silluq (e.g., יָשָֽׁב Ps. 1:1)

- 'ole weyored (e.g., חֶ֫פְצ֥וֹ Ps. 1:2 and פַּלְגֵ֫י מָ֥יִם Ps. 1:3)

- atnaḥ (e.g., הָרְשָׁעִ֑ים Ps. 1:4)[6]

- revia replacing atnaḥ (e.g., יֶהְגֶּ֗ה Ps. 1:2)[7]

- revia gadol preceded by a precursor (e.g., בְּעִתּ֗וֹ Ps. 1:3)[8]

- ṣinnor preceded by a precursor (e.g., הָלַךְ֮ Ps. 1:1).