Psalm 51 Poetic Structure

Guardian: Drew Longacre

Poetic Structure

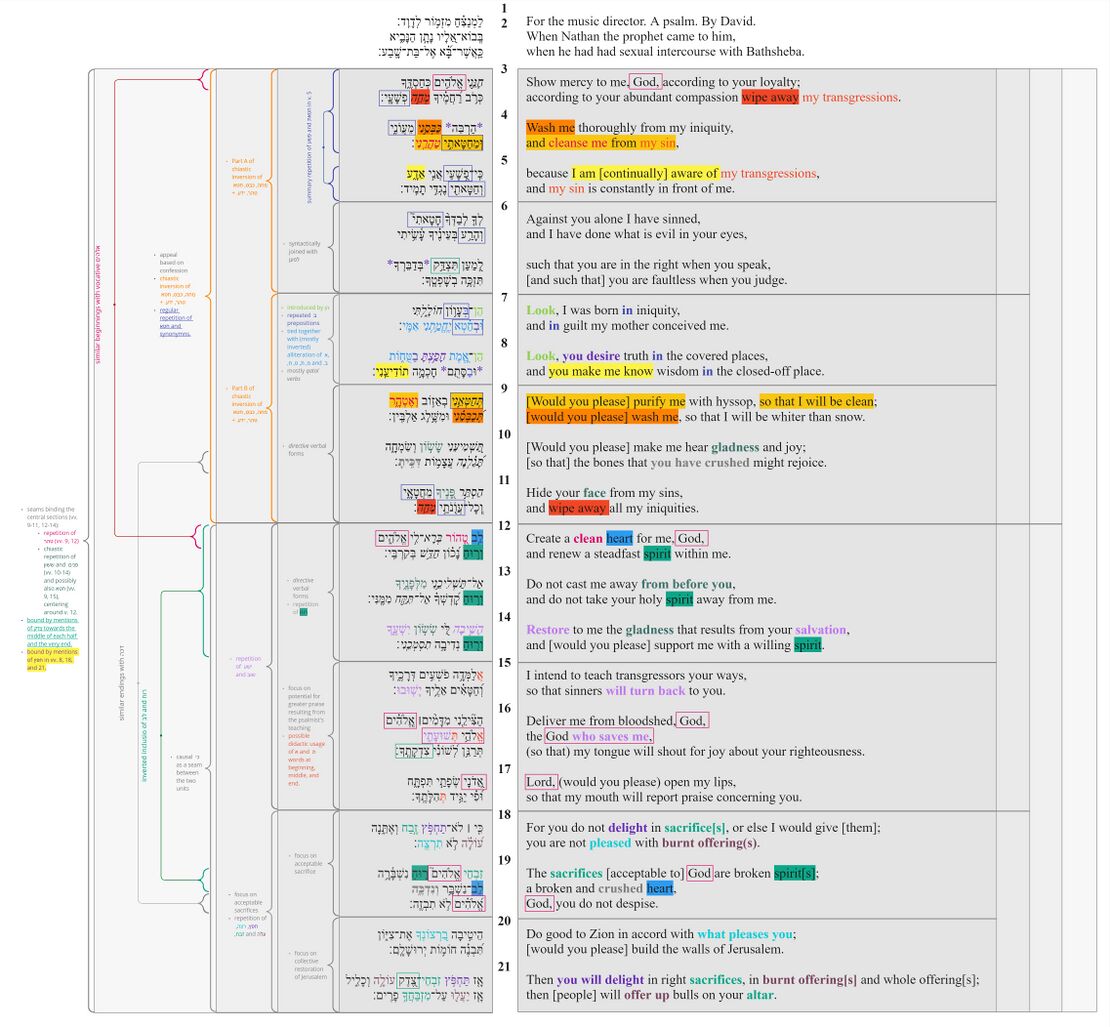

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into sub-sections, sub-sections into larger sections, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Macro-structure

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| v. 1 For the music director. A psalm. By David. | Superscription | |||

| v. 2 When Nathan the prophet came to him, when he had had sexual intercourse with Bathsheba. | ||||

| v. 3 Show mercy to me, God, according to your loyalty; according to your abundant compassion wipe away my transgressions. | Cleanse me | Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, for I have sinned! | guilt | |

| v. 4 Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin, | ||||

| v. 5 because I am [continually] aware of my transgressions, and my sin is constantly in front of me. | ||||

| v. 6 Against you alone I have sinned, and I have done what is evil in your eyes, such that you are in the right whenever you speak, [and such that] you are faultless whenever you judge. | ||||

| v. 7 Look, I was born in iniquity, and in guilt my mother conceived me. | ||||

| v. 8 Look, you desire truth in the covered places, and you make me know wisdom in the closed-off place. | ||||

| v. 9 [Would you please] purify me with hyssop, so that I will be clean; [would you please] wash me, so that I will be whiter than snow. | ||||

| v. 10 [Would you please] make me hear gladness and joy; [so that] the bones that you have crushed might rejoice. | ||||

| v. 11 Hide your face from my sins, and wipe away all my iniquities. | ||||

| v. 12 Create a clean heart for me, God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me. | Restore me | Create a clean heart for me, God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me! | hope | |

| v. 13 Do not cast me away from before you, and do not take your holy spirit away from me. | ||||

| v. 14 Restore to me the gladness that results from your salvation, and [would you please] support me with a willing spirit. | ||||

| v. 15 I intend to teach transgressors your ways, so that sinners will turn back to you. | Restore me | I intend to praise you and teach transgressors your ways. | determination | |

| v. 16 Deliver me from bloodshed, God, the God who saves me, [so that] my tongue will shout for joy about your righteousness. | ||||

| v. 17 Lord, [would you please] open my lips, so that my mouth will report praise concerning you. | ||||

| v. 18 For you do not delight in sacrifice[s], or else I would give [them]; you are not pleased with burnt offering[s]. | Restore us | The sacrifices acceptable to God are broken spirits and hearts. | contemplation | |

| v. 19 The sacrifices [acceptable to] God are broken spirit[s]; a broken and crushed heart, God, you do not despise. | ||||

| v. 20 Do good to Zion in accord with what pleases you; [would you please] build the walls of Jerusalem. | ||||

| v. 21 Then you will delight in right sacrifices, in burnt offering[s] and whole offering[s]; then [people] will offer up bulls on your altar. | Then you will delight in right sacrifices in Zion. | hope | ||

Notes

- There is no consensus concerning the poetic structure of Psalm 51, with scholars proposing a wide variety of conflicting subdivisions (for an extensive list of proposals, see van der Lugt 2010, 97-98). This is due, in large part, because, "The poet uses so many word repetitions that on this basis alone one can find (or impute) all sorts of structures" (Fokkelman 2000, 165). The correspondence between apparent structural features and thematic movements is also often unclear. Gunkel (1926) emphasized the development of ideas within the psalm as key to its structure (so vv. 3–4|5–6.7–8|9–11.12–14|15–17.18–19 [vv. 20–21 as an addition]), which has had an important impact on subsequent analysis of the psalm (e.g., Dalglish 1962, 75-77). On the other hand, many modern scholars have prioritized poetic indications for the structure of the text. Magne (1958) and others suppose a primarily bipartite psalm (at the highest level, vv. 3-11|12-19[21]). Van der Lugt (2010, 99), however, argues that "Magne’s view regarding the organization of the verbal repetitions is not the only possible one and it does not do justice to the thematic structure of this (individual) prayer." Van der Lugt's own rhetorical analysis proposes a tripartite structure similar to Gunkel (vv. 3-8, 9-14, 15-21). The structure proposed here attempts to balance a combination of key poetic structuring devices with thematic movements, while admitting that the two are not always perfectly aligned. Our analysis is closest to Magne, except that we join v. 5 to vv. 3-4 instead of v. 6 and we incorporate vv. 20-21.

- vv. 3-11. The first half of the psalm is structurally demarcated by the chiastic repetition of מחה, כבס, חטאּּ + טהר, and ידע, as well as the frequent repetition of the root חטא (and similar sounds, as in v. 8a) and other words for wrongdoing.

- v. 5. Thematically, v. 5 could be considered part of the confession of sin that follows (vv. 6-7; so Magne joins vv. 5-6), especially if כי is understood to scope over multiple verses (e.g., vv. 5-6; see Macrosyntax). But formally, it seems to form a tight unit with vv. 3-4 (so also van der Lugt), since it repeats the final keywords for wrongdoing from vv. 3-4 in a summary pattern. V. 5 would then provide the reason for the appeal. The beginning of a new section in v. 6 could also be supported by the double fronting in v. 6a-b (see Macrosyntax) and the shift to qatal verbs. If v. 5 is joined with vv. 3-4, then the subsections of the two parts of the chiastic structure in vv. 3-11 correspond perfectly in terms of number of bicola (3+2|2+3), but then the corresponding repetitions of ידע do not occur in corresponding subsections.

- vv. 6-7. Because the chiastic structure in the first half (vv. 3-11) is perfectly balanced in terms of bicola (3+2|2+3), there is no single bicolon at the exact center of the structure. Neither does there seem to be any particular thematic prominence within the psalm as a whole for the elements near the center, such as the justice of God (v. 6c-d) or the psalmist's birth in a sinful state (v. 7). Thus, the function of the chiasm seems to be binding vv. 3-11 together as a closed unit characterized by requesting grace on the basis of confession, rather than highlighting the confession itself.

- vv. 6, 16, 21. The root צדק occurs in vv. 6, 16, and 21 and helps tie the two halves of the psalm together. Vv. 6 and 16 both occur towards the middle of their respective halves of the psalm, while v. 21 concludes the psalm. The effect is to tie the two halves together by emphasizing that--though the psalmist is sinful (vv. 3-11)--God is righteous and expects righteousness from his people.

- v. 6c. The unexpected qal infinitive בְּדָבְרֶ֗ךָ (read as a piel infinitive in the grammar layer) appears to have been assimilated to the sound pattern of the following בְשָׁפְטֶֽךָ for poetic affect, though it is not clear whether this was originally intended by the poet or an innovation of the later reading tradition.

- vv. 10-14. The inverted repetition of ששון and פנים in vv. 10-11 and vv. 13-14 are intriguing, but seems subordinated to the primary bipartite structure of the psalm. Perhaps these repetitions serve to bind the two halves of the psalm and focus on v. 12, which is often perceived as the structural and rhetorical center of the psalm.

- vv. 12-19. (Most of) the second half of the psalm is bound by an inverted repetition of לב and רוח that functions as an inclusio encompassing vv. 12-19, which reinforces these terms as key to the thematic movements in the second half of the psalm.

- vv. 12-14. The three-fold fronted repetition of רוח (see Macrosyntax) may perhaps be taken as an indication of a discourse peak.

- v. 12. Despite proposing a tripartite structure of the psalm, van der Lugt (2010, 96) argues that "a caesura between vv. 11 and 12 divides the poem into two equal halves" and supposes v. 12 to be the "pivotal cola" in the middle of the psalm and also its "rhetorical centre." Similarly, Fokkelman (165) calls it the "center of the message" with regards to contents. If the poetic structure is viewed as bipartite as in our preferred analysis, this claim may find further support. V. 12 nicely blends the appeal for cleansing (cf. the repetition of טהר, which is also in vv. 4 and 9) from sin that characterizes the first half of the psalm with the appeal for spiritual restoration that characterizes the latter half. The reintroduction of the vocative אֱלֹהִ֑ים (last mentioned in v. 3 at the start of the first section) also supports the beginning of a new section here, as may the marked word order of both lines in v. 12 (see Macrosyntax).

- vv. 15-17. In this section, the first word begins with א and the last word begins with ת, the first and last letters of the alphabet respectively. Similarly, the two words in the middle of the unexpected tricolon in the middle of the section also begin with א and ת. Such alphabetic plays are characteristic of didactic poetry, so it is perhaps not coincidental to find such features here in this section where the psalmist focuses on his teaching role.

- vv. 20-21. Though the majority of commentators take vv. 20-21 as a secondary addition to the main body of the psalm (see Psalm 51:20-21 and the Story Behind Psalm 51), Fokkelman (2000) and van der Lugt (2010) join them with vv. 18-19 in the final major section of the psalm. Whether secondary or not, vv. 20-21 were clearly written to be read with vv. 18-19, given their clusters of repeated vocabulary. With the possible exception of חפץ (cf. v. 8), however, the repetitions in vv. 20-21 do not suggest a particularly close connection with other parts of the psalm. Vv. 20-21 are located outside the inclusio of לב and רוח that bind vv. 12-19, as well as the repetition of דכה that is found near the ends of both halves of the psalm (vv. 10, 19). In this context, vv. 20-21 envision collective restoration as an extension of the personal restoration envisioned in vv. 12-19.

Line Divisions

Line division divides the poem into lines and line groupings. We determine line divisions based on a combination of external evidence (Masoretic accents, pausal forms, manuscripts) and internal evidence (syntax, prosodic word counting and patterned relation to other lines). Moreover, we indicate line-groupings by using additional spacing.

When line divisions are uncertain, we consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. Then, if a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences our decision to divide the text at a certain point, we place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

| Poetic line division legend | |

|---|---|

| Pausal form | Pausal forms are highlighted in yellow. |

| Accent which typically corresponds to line division | Accents which typically correspond to line divisions are indicated by red text. |

| | | Clause boundaries are indicated by a light gray vertical line in between clauses. |

| G | Line divisions that follow Greek manuscripts are indicated by a bold green G. |

| DSS | Line divisions that follow the Dead Sea Scrolls are indicated by a bold green DSS. |

| M | Line divisions that follow Masoretic manuscripts are indicated by a bold green M. |

| Number of prosodic words | The number of prosodic words are indicated in blue text. |

| Prosodic words greater than 5 | The number of prosodic words if greater than 5 is indicated by bold blue text. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

- v. 4. For the vocalization of the ketiv הַרְבֵּה, see grammar note on v. 5 (MT qere: הֶ֭רֶב).

- v. 6. For the revocalization of בְּדַבֵּרְךָ, see grammar note on v. 6; MT:

- v. 8. For the revocalization of וּבַסָּתֻם, see grammar note on v. 8 (MT: וּ֝בְסָתֻ֗ם).

Notes

- Clear cases of enjambment across bicola include: vv. 4-5 and v. 6.

- v. 6c-d. While the Masoretic accents do not clearly indicate a minor break here, the graphic layout of the Aleppo could suggest this. With G, the parallel structure of the lines seems to require a subdivision of this verse here (so also van der Lugt).

- v. 16. The poetic position of אֱלֹהֵ֥י תְּשׁוּעָתִ֑י is difficult. The Masoretic accents suggest a minor break between אֱלֹהֵ֥י תְּשׁוּעָתִ֑י and הַצִּ֘ילֵ֤נִי מִדָּמִ֨ים׀ אֱֽלֹהִ֗ים, which is also graphically indicated in the layout in Sassoon 1053. On the other hand, the Aleppo codex and G join them graphically into a single line. The appositional phrase throws off the balance of lines (5:3) if joined to v. 16a, which would be by far the longest line in the psalm by syllable count. If this line originally read יהוה אֱלֹהֵ֥י תְּשׁוּעָתִ֑י before the Elohistic redaction, then the line may have been slightly shorter in terms of syllable count, but still longer than expected. If אֱלֹהֵ֥י תְּשׁוּעָתִ֑י is treated as a separate poetic line as here, then this would be one of only a few possible cases of a tricolon in this psalm, which everywhere else consists of clear bicola. Van der Lugt separates אֱלֹהֵ֥י תְּשׁוּעָתִ֑י as its own half-line, plausibly joining v. 16c with v.17a-b as a tricolon, which seems difficult with the intervening vocative אֲ֭דֹנָי. A similar question arises with the analysis of the appositional עוֹלָ֣ה וְכָלִ֑יל in v. 21a and the long line in v. 19b-c.

- v. 18a. The MT accents and pausal form (and the graphic layout of the Aleppo codex, Sassoon 1053, and G) read וְאֶתֵּ֑נָה with v. 18a (so also van der Lugt). Some modern translations read וְאֶתְּנָה with v. 18b (e.g., NRSV), which may yield somewhat better line balance. If וְאֶתֵּ֑נָה is read with v. 18a, the lines are somewhat imbalanced with 4:3 prosodic words, but only if לֹא־תַחְפֹּ֣ץ is read as one prosodic word and לֹ֣א תִרְצֶֽה as two with the MT (inconsistently). If these two phrases are treated similarly, then we would have either a 4:2 or 5:3 imbalance in terms of prosodic words, which seems unexpected and potentially problematic given the established patterns in the psalm. If the non-pausal וְאֶתְּנָה is read with v. 18b yields and לֹ֣א תִרְצֶֽה is read as one prosodic unit as is לֹא־תַחְפֹּ֣ץ in v. 18a, then the verse would have a perfect 3:3 balance. Nevertheless, by syllable count, the imbalance is minimal, and both כִּ֤י ׀ לֹא־תַחְפֹּ֣ץ זֶ֣בַח (consisting of 5 or 6 syllables) and ע֝וֹלָ֗ה לֹ֣א תִרְצֶֽה (consisting of 5 syllables) are roughly the same, in which case וְאֶתְּנָה could go with either line. Thus, in this case, the argument from line balance does not seem compelling enough to outweigh the strong consensus of the reading tradition.

- v. 19b-c. After v. 16a-b (and similar to v. 21a), לֵב־נִשְׁבָּ֥ר וְנִדְכֶּ֑ה אֱ֝לֹהִ֗ים לֹ֣א תִבְזֶֽה would be the longest line in the psalm in terms of syllable count. Thus, the Masoretes have broken this string up into two parts with the atnach accent, yielding an unusual tricolon (cf. v. 16; so also van der Lugt). This minor division also appears to be indicated in the graphic layout of the Aleppo Codex. In contrast, G reads v. 19b-c as a single poetic line. Breaking v. 19b-c apart works very well metrically, but creates an awkward semantic break with poetic enjambment. Van der Lugt alternatively suggests that נִשְׁבָּ֥ר וְ could be omitted on quantitative grounds, leaving a bicolon (96).

- vv. 20-21. These lines are notably longer than the average line length throughout vv. 1-19, both in terms of prosidic words and syllable counts (so also van der Lugt). This could be considered support for interpreting these lines as secondary to the main body of the psalm, but such need not be the case. This tension would be somewhat alleviated if עוֹלָ֣ה וְכָלִ֑יל were read as the second line of a tricolon with G, against the MT division. For the similar breaking of long lines, see. vv. 16 and 19.