Psalm 111 Discourse

Guardian: Ryan Sikes

About the Discourse Layer

Our Discourse Layer includes four additional layers of analysis:

- Participant analysis

- Macrosyntax

- Speech act analysis

- Emotional analysis

For more information on our method of analysis, click the expandable explanation button at the beginning of each layer.

Participant Analysis

Participant Analysis focuses on the characters in the psalm and asks, “Who are the main participants (or characters) in this psalm, and what are they saying or doing? It is often helpful for understanding literary structure, speaker identification, etc.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Participant Analysis Creator Guidelines.

There are three participants/characters in Psalm 111:

Profile List

| Psalmist |

| Upright people |

| "The congregation" (v. 2) |

| "Those who delight in YHWH's deeds" (v. 2) |

| "Those who feared him" (v. 5) |

| "YHWH's people" (v. 6) |

| "Those who practice YHWH's commands" (v. 10) |

| YHWH |

| Nations |

Profile Notes

- Psalmist/Upright People: While the first-person singular reference in v. 1 constitutes a distinct participant, the psalmist presents himself as being present with the upright people, in the congregation (v. 1c). Thus, the psalmist describes himself as a subset of the upright people.

| Text (Hebrew) | Verse | Text (CBC) The Close-but-clear translation (CBC) exists to provide a window into the Hebrew text according to how we understand its syntax and word-to-phrase-level semantics. It is designed to be "close" to the Hebrew, while still being "clear." Specifically, the CBC encapsulates and reflects the following layers of analysis: grammar, lexical semantics, phrase-level semantics, and verbal semantics. It does not reflect our analysis of the discourse or of poetics. It is not intended to be used as a stand-alone translation or base text, but as a supplement to Layer-by-Layer materials to help users make full use of these resources. |

|---|---|---|

הַ֥לְלוּ יָ֨הּ ׀

|

1a | Praise Yah!

|

אוֹדֶ֣ה יְ֭הוָה בְּכָל־לֵבָ֑ב

|

1b | I will praise YHWH whole-heartedly

|

בְּס֖וֹד יְשָׁרִ֣ים וְעֵדָֽה׃

|

1c | in the council of upright people, in the congregation.

|

גְּ֭דֹלִים מַעֲשֵׂ֣י יְהוָ֑ה

|

2a | YHWH’s deeds are great,

|

דְּ֝רוּשִׁ֗ים לְכָל־חֶפְצֵיהֶֽם׃

|

2b | studied by all who delight in them.

|

הוֹד־וְהָדָ֥ר פָּֽעֳל֑וֹ

|

3a | His work is glorious and majestic,

|

וְ֝צִדְקָת֗וֹ עֹמֶ֥דֶת לָעַֽד׃

|

3b | and his righteousness stands forever.

|

זֵ֣כֶר עָ֭שָׂה לְנִפְלְאֹתָ֑יו

|

4a | He has caused his wonderful acts to be remembered.

|

חַנּ֖וּן וְרַח֣וּם יְהוָֽה׃

|

4b | YHWH is merciful and compassionate.

|

טֶ֭רֶף נָתַ֣ן לִֽירֵאָ֑יו

|

5a | He gave food to those who feared him.

|

יִזְכֹּ֖ר לְעוֹלָ֣ם בְּרִיתֽוֹ׃

|

5b | He will remember his covenant forever.

|

כֹּ֣חַ מַ֭עֲשָׂיו הִגִּ֣יד לְעַמּ֑וֹ

|

6a | He showed his people the power of his deeds

|

לָתֵ֥ת לָ֝הֶ֗ם נַחֲלַ֥ת גּוֹיִֽם׃

|

6b | by giving them nations as an inheritance.

|

מַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָ֭דָיו אֱמֶ֣ת וּמִשְׁפָּ֑ט

|

7a | The deeds of his hands are faithful and just.

|

נֶ֝אֱמָנִ֗ים כָּל־פִּקּוּדָֽיו׃

|

7b | All his commandments are enduring,

|

סְמוּכִ֣ים לָעַ֣ד לְעוֹלָ֑ם

|

8a | established forever and ever,

|

עֲ֝שׂוּיִ֗ם בֶּאֱמֶ֥ת וְיָשָֽׁר׃

|

8b | practiced in faithfulness and uprightness.

|

פְּד֤וּת ׀ שָׁ֘לַ֤ח לְעַמּ֗וֹ

|

9a | He sent redemption to his people.

|

צִוָּֽה־לְעוֹלָ֥ם בְּרִית֑וֹ

|

9b | He commanded his covenant forever.

|

קָד֖וֹשׁ וְנוֹרָ֣א שְׁמֽוֹ׃

|

9c | His name is holy and awesome.

|

רֵ֘אשִׁ֤ית חָכְמָ֨ה ׀ יִרְאַ֬ת יְהוָ֗ה

|

10a | Fearing YHWH is the beginning of wisdom;

|

שֵׂ֣כֶל ט֭וֹב לְכָל־עֹשֵׂיהֶ֑ם

|

10b | all who practice them have good insight.

|

תְּ֝הִלָּת֗וֹ עֹמֶ֥דֶת לָעַֽד׃

|

10c | His praiseworthiness stands forever.

|

Notes

- v. 10: תְּהִלָּתוֹ "his praise" — YHWH or righteous person?

- The 3ms suffix on תְּהִלָּתוֹ might refer either to YHWH or to a person who fears YHWH and keeps his commands.

- The suffix probably refers to YHWH, who is the topic of the psalm and the referent of every other 3ms suffix. The correspondence between v. 10c and v. 3b and the inclusio of v. 1 (אוֹדֶה) and v. 10 (תְּהִלָּתוֹ) also support identifying YHWH as the subject.[1]

- Some scholars have argued that the 3ms suffix refers to a person who fears YHWH, either as an objective genitive ("his praise" = "the praise which he receives")[2] or a subjective genitive ("his praise" = "the praise which he gives").[3] But if this were the case, then we might have expected a 3mp suffix.

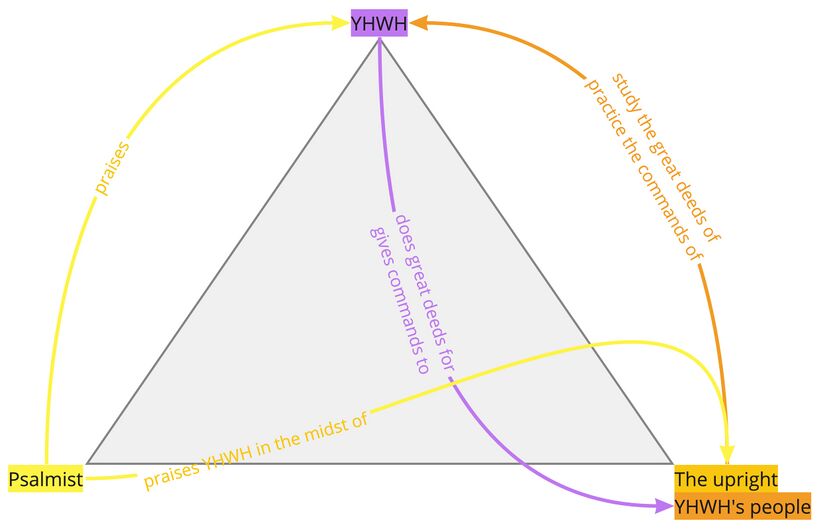

Participant Relations Diagram

The relationships among the participants may be abstracted and summarized as follows:

Macrosyntax

Macrosyntax Diagram

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[4] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[5] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

There are no notes on divisions for this psalm.

- v. 2a. The fronting of גְּדֹלִים is poetic (ג line of acrostic) and probably also information-structural. Although "YHWH's deeds" have not been mentioned until this point, they are implied by אודה יהוה in the previous verse—the word אודה means "action by which humans openly express recognition of what someone else has done or achieved" (SDBH, italics added). The fronted predicate thus "establishes... [the] state or features... of the discourse active subject of a verbless clause" (BHRG 47.3.2).

- v. 3a. The fronting of הוֹד־וְהָדָר is, like גְּדֹלִים, both poetic (ה line of acrostic) and information-structural (cf. BHRG 47.3.2).

- v. 4a. The fronting of the object זֵכֶר is probably poetic, fitting the acrostic structure (ז line). The placement of לְנִפְלְאֹתָיו at the end of the line, even though it modifies the זֵכֶר, might be due to the length of לְנִפְלְאֹתָיו.

- v. 4b. The fronting of חַנּוּן וְרַחוּם is poetic, and, like the other verbless clauses in the psalm (vv. 2a, 3a, 9c, 10a), probably also information–structural (cf. BHRG 47.3.2).

- v. 5a. The fronting of the object טֶרֶף is poetic, fitting the acrostic structure (ט line).

- v. 5b. The adverbial לְעוֹלָם is placed before the object, probably to stress YHWH's ongoing commitment to his covenant: YHWH's covenant faithfulness is not just a matter of the past (cf. v. 5a). Rather, he will remember his covenant forever.

- v. 6a. The fronting of כֹּחַ מַעֲשָׂיו is probably poetic, fitting the acrostic structure (כ line).

- v. 7b. The fronting of the predicate נֶאֱמָנִים is poetic, both fitting the acrostic (נ line) and forming a chiasm in v. 7: S SC [אמת] // SC [אמן] S]).

- v. 9a. The fronting of the object פְּדוּת is poetic, both fitting the acrostic (פ line) and strengthening a correspondence with v. 6a (כֹּ֣חַ מַ֭עֲשָׂיו הִגִּ֣יד לְעַמּ֑וֹ), which also has a fronted object and the exact phrase לְעַמּוֹ (see poetic structure) (cf. Lunn 2006:327 "DEF").

- v. 9b. לְעוֹלָם (see v. 5b)

- v. 9c. The fronting of קָדוֹשׁ וְנוֹרָא is poetic (ק line of acrostic) and, like many of the other verbless clauses in the psalm (vv. 2a, 3a, 4b, 10a), probably also information structural (cf. BHRG 47.3.2).

- v. 10a. The fronting of רֵאשִׁית חָכְמָה is poetic (ר line of acrostic) and, like many of the other verbless clauses in the psalm (vv. 2a, 3a, 4b, 9c), probably also information structural (cf. BHRG 47.3.2). The subject יִרְאַת יְהוָה was implied in the previous line (נוֹרָא) and is therefore active in the discourse.

There are no notes on vocatives for this psalm.

There are no notes on discourse markers for this psalm.

There are no notes on conjunctions for this psalm.

Speech Act Analysis

The Speech Act layer presents the text in terms of what it does, following the findings of Speech Act Theory. It builds on the recognition that there is more to communication than the exchange of propositions. Speech act analysis is particularly important when communicating cross-culturally, and lack of understanding can lead to serious misunderstandings, since the ways languages and cultures perform speech acts varies widely.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Speech Act Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Speech Act Analysis Chart

The following chart is scrollable (left/right; up/down).

| Verse | Hebrew | CBC | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) |

| Verse number and poetic line | Hebrew text | English translation | Declarative, Imperative, or Interrogative Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

Assertive, Directive, Expressive, Commissive, or Declaratory Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

More specific illocution type with paraphrased context | Illocutionary intent (i.e. communicative purpose) of larger sections of discourse These align with the "Speech Act Summary" headings |

What the speaker intends for the address to think | What the speaker intends for the address to feel | What the speaker intends for the address to do |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| Verse | Text (Hebrew) | Text (CBC) The Close-but-clear translation (CBC) exists to provide a window into the Hebrew text according to how we understand its syntax and word-to-phrase-level semantics. It is designed to be "close" to the Hebrew, while still being "clear." Specifically, the CBC encapsulates and reflects the following layers of analysis: grammar, lexical semantics, phrase-level semantics, and verbal semantics. It does not reflect our analysis of the discourse or of poetics. It is not intended to be used as a stand-alone translation or base text, but as a supplement to Layer-by-Layer materials to help users make full use of these resources. | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) | Speech Act Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | הַ֥לְלוּ יָ֨הּ ׀ | Praise Yah! | Superscription | • The psalmist effectively announces the global speech act at the beginning of the psalm: אוֹדֶה יְהוָה (cf. Ps. 9; 138; cf. other Pss. beginning with הודו [e.g., Pss. 105; 106; 107; 118; 136] or הודינו [Ps. 75]). In most of these Psalms, there is an emphasis throughout on YHWH's great deeds, especially his past acts of deliverance (cf. the frequent parallel of ידה/תודה and ספר נפלאות [e.g., Pss. 9:2; 26:7; 75:2; cf. 79:13; 107:22]). A number of the psalms in the Qumran Hodayot also begin with אודה/אודך. • The verb "praise" (ידה hiphil) refers to an "action by which humans openly express recognition of what someone else has done or achieved" (SDBH). (See lexical semantics for details.) • One object of the praise is to move the hearers ("the upright," v. 1) to keep YHWH's commands (cf. vv. 7b, 9bc, 10ab). The appropriate response to what YHWH has done is to do what YHWH has commanded; the appropriate response to his covenant faithfulness (cf. v. 5b) is covenant faithfulness (cf. v. 9b).

| |||||||

| אוֹדֶ֣ה יְ֭הוָה בְּכָל־לֵבָ֑ב | I will praise YHWH whole-heartedly | Imperative | Commissive | Expressing his desire and intention to praise YHWH. | Praising YHWH. | Listeners will consider themselves as part of the congregation of the upright. | Listeners will be whole-heartedly determined to praise YHWH. | Listeners will join the psalmist in praising YHWH. | • Although אוֹדֶה, in terms of its morphology, could be either a yiqtol or a cohortative, its use in similar contexts alongside morphologically cohortative verbs suggests that it is a cohortative here as well (cf. Pss. 7:18; 9:2–3; 54:8). • "The cohortative expresses the will or strong desire of the speaker. In cases where the speaker has the ability to carry out an inclination it takes on the coloring of resolve ('I will...')" (IBHS 34.5.1)

| ||

| בְּס֖וֹד יְשָׁרִ֣ים וְעֵדָֽה׃ | in the council of upright people, in the congregation. | ||||||||||

| 2 | גְּ֭דֹלִים מַעֲשֵׂ֣י יְהוָ֑ה | YHWH’s deeds are great, | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his great deeds. | Listeners will acknowledge the wondrous nature of YHWH's works. | Listeners will praise YHWH for his wondrous works. | ||||

| דְּ֝רוּשִׁ֗ים לְכָל־חֶפְצֵיהֶֽם׃ | studied by all who delight in them. | ||||||||||

| 3 | הוֹד־וְהָדָ֥ר פָּֽעֳל֑וֹ | His work is glorious and majestic, | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his glorious and majestic work. | ||||||

| וְ֝צִדְקָת֗וֹ עֹמֶ֥דֶת לָעַֽד׃ | and his righteousness stands forever. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his enduring righteousness. | |||||||

| 4 | זֵ֣כֶר עָ֭שָׂה לְנִפְלְאֹתָ֑יו | He has caused his wonderful acts to be remembered. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for causing his wonderful acts to be remembered. | Listeners will remember YHWH's covenant faithfulness. | Listeners will be faithful to YHWH's covenant. | ||||

| חַנּ֖וּן וְרַח֣וּם יְהוָֽה׃ | YHWH is merciful and compassionate. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his mercy and compassion. | |||||||

| 5 | טֶ֭רֶף נָתַ֣ן לִֽירֵאָ֑יו | He gave food to those who feared him. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for providing for his people. | ||||||

| יִזְכֹּ֖ר לְעוֹלָ֣ם בְּרִיתֽוֹ׃ | He will remember his covenant forever. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his covenant faithfulness. | |||||||

| 6 | כֹּ֣חַ מַ֭עֲשָׂיו הִגִּ֣יד לְעַמּ֑וֹ | He showed his people the power of his deeds | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his demonstration of strength. | ||||||

| לָתֵ֥ת לָ֝הֶ֗ם נַחֲלַ֥ת גּוֹיִֽם׃ | by giving them nations as an inheritance. | ||||||||||

| 7 | מַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָ֭דָיו אֱמֶ֣ת וּמִשְׁפָּ֑ט | The deeds of his hands are faithful and just. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his faithful and just deeds. | Listeners will acknowledge the righteousness of YHWH's commands. | Listeners will do what YHWH has commanded. | ||||

| נֶ֝אֱמָנִ֗ים כָּל־פִּקּוּדָֽיו׃ | All his commandments are enduring, | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his commandments. | |||||||

| 8 | סְמוּכִ֣ים לָעַ֣ד לְעוֹלָ֑ם | established forever and ever, | |||||||||

| עֲ֝שׂוּיִ֗ם בֶּאֱמֶ֥ת וְיָשָֽׁר׃ | practiced in faithfulness and uprightness. | ||||||||||

| 9 | פְּד֤וּת ׀ שָׁ֘לַ֤ח לְעַמּ֗וֹ | He sent redemption to his people. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for redeeming his people. | Listeners will remember YHWH's holiness and covenant faithfulness. | Listeners will be faithful to YHWH's covenant. | ||||

| לְעַמּ֗וֹ צִוָּֽה־לְעוֹלָ֥ם בְּרִית֑וֹ | He commanded his covenant forever. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for commanding his covenant. | |||||||

| קָד֖וֹשׁ וְנוֹרָ֣א שְׁמֽוֹ׃ | His name is holy and awesome. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his holiness and awesomeness. | |||||||

| 10 | רֵ֘אשִׁ֤ית חָכְמָ֨ה ׀ יִרְאַ֬ת יְהוָ֗ה | Fearing YHWH is the beginning of wisdom; | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for the wisdom that comes from fearing him. | Listeners will value the fear of YHWH and wisdom. | Listeners will be in reverent fear of YHWH. | Listeners will keep YHWH's commandments; listeners will praise YHWH. | |||

| שֵׂ֣כֶל ט֭וֹב לְכָל־עֹשֵׂיהֶ֑ם | all who practice them have good insight. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for the good insight that comes from practicing his commands. | |||||||

| תְּ֝הִלָּת֗וֹ עֹמֶ֥דֶת לָעַֽד׃ | His praiseworthiness stands forever. | Declarative | Assertive | Praising YHWH for his enduring praiseworthiness. | |||||||

Emotional Analysis

This layer explores the emotional dimension of the biblical text and seeks to uncover the clues within the text itself that are part of the communicative intent of its author. The goal of this analysis is to chart the basic emotional tone and/or progression of the psalm.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Emotional Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Emotional Analysis Chart

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| Verse | Text (Hebrew) | Text (CBC) The Close-but-clear translation (CBC) exists to provide a window into the Hebrew text according to how we understand its syntax and word-to-phrase-level semantics. It is designed to be "close" to the Hebrew, while still being "clear." Specifically, the CBC encapsulates and reflects the following layers of analysis: grammar, lexical semantics, phrase-level semantics, and verbal semantics. It does not reflect our analysis of the discourse or of poetics. It is not intended to be used as a stand-alone translation or base text, but as a supplement to Layer-by-Layer materials to help users make full use of these resources. | The Psalmist Feels | Emotional Analysis Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | הַ֥לְלוּ יָ֨הּ ׀ | Praise Yah! | ||

| אוֹדֶ֣ה יְ֭הוָה בְּכָל־לֵבָ֑ב | I will praise YHWH whole-heartedly | • Sincere wholehearted determination that he will praise YHWH. | • Praise implies admiration, respect, and gratitude • PP: לבב (see notes on phrase-level semantics; cf. Pss. 9:1; 86:12; 138:2; Deut. 6:5; etc. collocated with באמת in 1 Kgs. 2:4; often collocated with בכל נפש)

| |

| בְּס֖וֹד יְשָׁרִ֣ים וְעֵדָֽה׃ | in the council of upright people, in the congregation. | |||

| 2 | גְּ֭דֹלִים מַעֲשֵׂ֣י יְהוָ֑ה | YHWH’s deeds are great, | • Delight in YHWH's deeds. | • The term חָפֵץ refers to a "state in which humans feel emotionally attached to a particular event" (SDBH). |

| דְּ֝רוּשִׁ֗ים לְכָל־חֶפְצֵיהֶֽם׃ | studied by all who delight in them. | |||

| 3 | הוֹד־וְהָדָ֥ר פָּֽעֳל֑וֹ | His work is glorious and majestic, | ||

| וְ֝צִדְקָת֗וֹ עֹמֶ֥דֶת לָעַֽד׃ | and his righteousness stands forever. | |||

| 4 | זֵ֣כֶר עָ֭שָׂה לְנִפְלְאֹתָ֑יו | He has caused his wonderful acts to be remembered. | • Awe over YHWH's wonderful acts. | • The term פלא refers to a "state in which an event is out of the ordinary and inspiring amazement" (SDBH). |

| חַנּ֖וּן וְרַח֣וּם יְהוָֽה׃ | YHWH is merciful and compassionate. | |||

| 5 | טֶ֭רֶף נָתַ֣ן לִֽירֵאָ֑יו | He gave food to those who feared him. | ||

| יִזְכֹּ֖ר לְעוֹלָ֣ם בְּרִיתֽוֹ׃ | He will remember his covenant forever. | • Hope that YHWH will again remember his covenant and perform great deeds. | ||

| 6 | כֹּ֣חַ מַ֭עֲשָׂיו הִגִּ֣יד לְעַמּ֑וֹ | He showed his people the power of his deeds | ||

| לָתֵ֥ת לָ֝הֶ֗ם נַחֲלַ֥ת גּוֹיִֽם׃ | by giving them nations as an inheritance. | |||

| 7 | מַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָ֭דָיו אֱמֶ֣ת וּמִשְׁפָּ֑ט | The deeds of his hands are faithful and just. | ||

| נֶ֝אֱמָנִ֗ים כָּל־פִּקּוּדָֽיו׃ | All his commandments are enduring, | • Sincerely devoted to YHWH's commands | • The phrase באמת וישר reflects the psalmist's own attitude (cf. בכל לבב in v. 1). | |

| 8 | סְמוּכִ֣ים לָעַ֣ד לְעוֹלָ֑ם | established forever and ever, | ||

| עֲ֝שׂוּיִ֗ם בֶּאֱמֶ֥ת וְיָשָֽׁר׃ | practiced in faithfulness and uprightness. | |||

| 9 | פְּד֤וּת ׀ שָׁ֘לַ֤ח לְעַמּ֗וֹ | He sent redemption to his people. | • Devotion to YHWH as master/owner. | |

| לְעַמּ֗וֹ צִוָּֽה־לְעוֹלָ֥ם בְּרִית֑וֹ | He commanded his covenant forever. | |||

| קָד֖וֹשׁ וְנוֹרָ֣א שְׁמֽוֹ׃ | His name is holy and awesome. | • Awe at YHWH's holy and awesome character (name). | • The term ירא refers to a "state in which humans, deities, places and activities have qualities that inspire fear in others" (SDBH). | |

| 10 | רֵ֘אשִׁ֤ית חָכְמָ֨ה ׀ יִרְאַ֬ת יְהוָ֗ה | Fearing YHWH is the beginning of wisdom; | • Awe/fear of YHWH. | • The term יִרְאָה refers to a "state in which humans experience fear" (SDBH). |

| שֵׂ֣כֶל ט֭וֹב לְכָל־עֹשֵׂיהֶ֑ם | all who practice them have good insight. | |||

| תְּ֝הִלָּת֗וֹ עֹמֶ֥דֶת לָעַֽד׃ | His praiseworthiness stands forever. | • The term תְּהִלָּה refers to a "state in which humans or deities are considered worthy of praise" (SDBH). |

Affective Circumplex

Bibliography

- Allen, Leslie. 1983. Psalms 101-150. WBC 21. Waco: Word Books.

- Auffret, Pierre. 1997. “Grandes sont les œuvres de YHWH: Etude structurelle du Psaume 111.” JNES 56 (3): 183–96.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi. 2009. “The Riddle of Psalm 111.” Pages 62–73 in Scriptural Exegesis. Edited by Deborah A. Green and Laura S. Lieber. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dahood, Mitchell J. 1970. Psalms III, 101-150. AB 17A. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Ehrlich, Arnold B. 1905. Die Psalmen; neu übersetzt und erklärt. Berlin: Poppelauer.

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2003. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 3: The Remaining 65 Psalms). Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Gesenius, W. Donner, H. Rüterswörden, U. Renz, J. Meyer, R., eds. 2013. Hebräisches und aramäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament. 18. Auflage Gesamtausgabe. Berlin: Springer.

- Gordon, Amnon. 1982. “The Development of the Participle in Biblical, Mishnaic, and Modern Hebrew.” Afroasiatic Linguistics 8 (3): 121–179.

- Hensley, Adam D. 2018. Covenant Relationships and the Editing of the Hebrew Psalter. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, volume 666. New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 2011. Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101-150. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1871. Die Psalmen. Vol. 4. Gotha: F.A. Perthes.

- Hurvitz, Avi. 2016. A Concise Lexicon of Late Biblical Hebrew: Linguistic Innovations in the Writings of the Second Temple Period. Leiden: Brill.

- Jastrow, Marcus. 1926. Dictionary of Targumim, Talmud and Midrashic Literature. New York: Verlag Choreb.

- Jenni, Ernst. 1992. Die hebräischen Präpositionen Band 1: Die Präposition Beth. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer.

- ________. 2000. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 3: Die Präposition Lamed. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer.

- Kiel, Jonathan M. 2022. “A New Thematic Structure for Psalm 111.” Page 107–128 in Like Nails Firmly Fixed (Qoh 12:11): Essays on the Text and Language of the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures, Presented to Peter J. Gentry on the Occasion of His Retirement. Edited by Phillip S. Marshall, John D. Meade, and Jonathan M. Kiel. Leuven: Peeters.

- Kohler, Ludwig. 1954. Hebrew Man. New York: Abingdon Press.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2013. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90–150 and Psalm 1. Vol. 3. Oudtestamentische Studiën 63. Leiden: Brill.

- Niccacci, Alviero. 2006. “The Biblical Hebrew Verbal System in Poetry.” Page 247–68 in Biblical Hebrew in Its Northwest Semitic Setting: Typological and Historical Perspectives. Edited by Steven E. Fassberg and Avi Hurvitz. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Magnes Press.

- Notarius, Tania. 2010. “The Active Predicative Participle in Archaic and Classical Biblical Poetry.” ANES 47: 241–69.

- Radak. Radak on Psalms.

- Robertson, O. Palmer. 2015. “The Strategic Placement of the ‘Hallelu-Yah’ Psalms within the Psalter.” JETS 58 (2): 165–68.

- Scoralick, Ruth. 1997. “Psalm 111 : Bauplan und Gedankengang.” Biblica 78 (2): 190–205.

- Weber, Beat. 2003. “Zu Kolometrie Und Strophischer Struktur von Psalm 111.” Biblische Notizen 118: 62–67.

Footnotes

- ↑ Cf. Baethgen 1904; Scoralick 1997; Allen 2002; Zenger 2011.

- ↑ cf. Delitzsch, in light of Ps. 112.

- ↑ Cf. Wolff 1961.

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.