Psalm 46 Poetic Features

Guardian: Ekaterina Kozlova

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

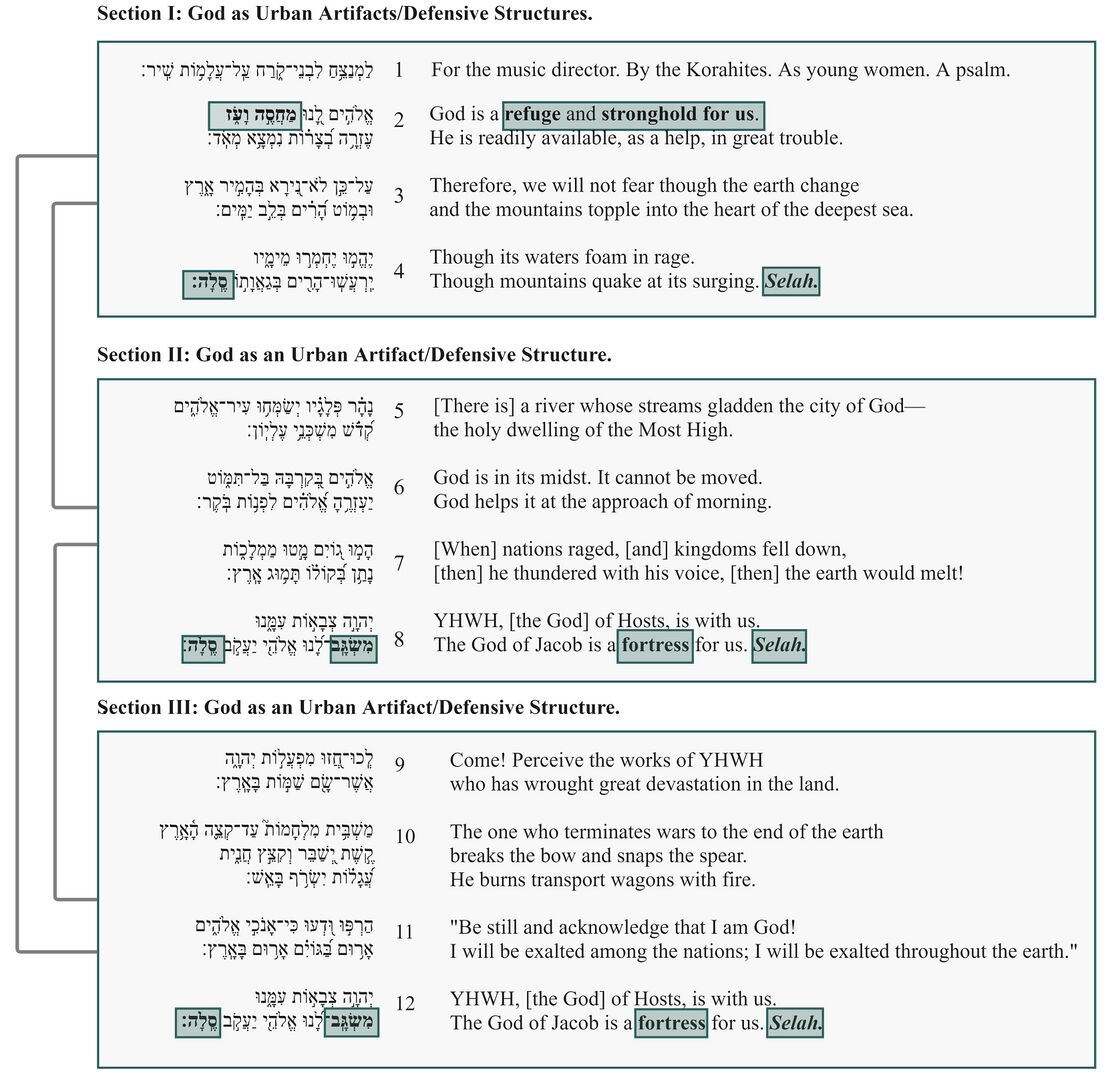

God As Urban Architecture/Defensive Structures

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

The first section (vv. 2–4) in Psalm 46 utilizes terminology related to space and architecture to describe God in relation to his city and its people. Thus, he is imaged as a refuge (מחסה) and as a stronghold (עז). Based on Amos 3:11 and Prov 21:22, SDBH defines עז as “a construction that is strong and able to resist attacks--stronghold” (cf. Ps 61:3 [מחסה לי מגדל־עז מפני אויב׃]; Ps 91:2 [מחסי ומצודתי אלהי]; Jer 16:19 [יהוה עזי ומעזי ומנוסי]; Joel 3:16 [ויהוה מחסה לעמו ומעוז לבני ישראל]). The second and third sections (vv. 5–7 and vv. 9–11) are followed by a refrain (vv. 8, 12), wherein God is said to be a fortress (משגב), “a high and unattainable location, either because of its natural environment or as a result of human construction efforts" (SDBH). Furthermore, all three sections (vv. 4, 8, 12) finish with a סלה, a musical term, which echoes the Hebrew word “rock” (סלע). Notably, as an epithet for God, סלע appears in the Psalms alongside terms such as “refuge”, “fortress”, and “stronghold” (e.g., Ps 18:3: יהוה ׀ סלעי ומצודתי ומפלטי אלי צורי אחסה־בו מגני וקרן־ישעי משגבי; cf. Ps 31:4).

Effect

Urbicide, “the strategic immolation of cities”, is a well-attested phenomenon in ancient warfare. In urbicide, kings at war target their opponents’ cities as political and cultural centers.[1] Echoing ANE and HB urbicide texts, Psalm 46 speaks of political tumult, whereby nations and kingdoms foam in rage, but totter and fall down (v. 7; cf. vv. 3–4); the land around God's city is said to change and shake, but is subdued and turned into desolation (vv. 3, 9). Amidst such turmoil, however, the city of God stands; it is said to never move/totter/fall down (v. 7). If in cases of successful urbicide, cities are razed to the ground, turned into heaps of ruins, and become eternal tells[2] of desolation (e.g., Josh 8:28), then Psalm 46's city is immovable. This is due to its protection by God, its divine patron, who is conceptualized through spatial and architectural metaphors (vv. 2, 8, 12). In this would-be urbicide text, God is said to be in the midst of the city (v. 6) and is part of the city-scape, i.e., he is a “refuge”, “stronghold”, and “fortress”. Additionally, located in close proximity to terms connoting architectural structures, the word Selah reinforces the image of God as a strong, immovable landmark. In a song about attempted urbicide, metaphorizing God as urban artifacts and defensive structures links the city’s fate with God’s own and guarantees its inviolability. Through this rhetorical move, the urbanization of God indicates the fortification of his city.

Intoxication and Warfare

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

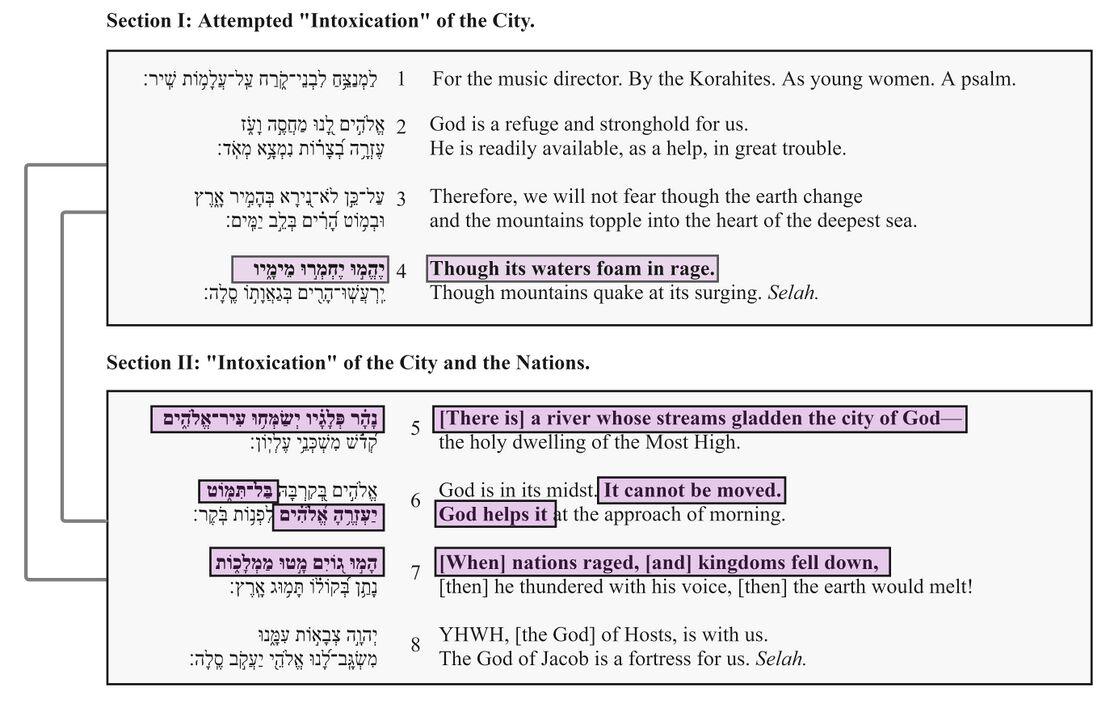

Alcoholic intoxication, especially with wine, was a common image used throughout the Hebrew Bible, with both negative and positive connotations. Negatively, it was common to speak of forcing a recipient to drink wine and become drunk as a metaphor for assault, judgment, and destruction, as in Jer 25:15-16 where God says “Take this cup of the wine of wrath from my hand and cause all the nations to whom I send you to drink it. They will stagger and go mad because of the sword that I will send among them” (see also Isa 29:9–10; Jer 49:12–13, 51:7; Hab 2:15–16; Lam 4:21; Ezek 23:31–34; Obad 1:16; Zech 12:2; Isa 51:17–23; cf. Job 21:20; Ps 60:3, 75:8). Positively, however, wine was associated with joy, abundance, and provision, as in Ps 104:15 where God provides "wine which makes man's heart glad" (ויין ׀ ישמח לבב־אנוש) (cf. Eccl 10:19). In Psalm 46, this image is used in three ways. First, the nations are depicted as seeking to intoxicate the city of God (vv. 3–4, 7), echoing the negative imagery of wine of wrath. Second, God is depicted as "making glad" the city and its residents (v. 5), echoing the positive imagery of good wine, and protecting them from the intoxication of the enemies (v. 6). Finally, God is depicted as intoxicating the nations, again echoing the negative imagery (v. 7, cf vv. 9–10). This unfolds through the psalm in the following way:

Section I: Attempted “Intoxication” of the City. In section I, the city of God is seen under attack from the hostile forces, metaphorized as chaotic waters (The Raging Waters in Psalm46:2-4). These in turn rage (המה; cf. Prov 20:1)[3] and foam (חמר; cf. Ps 75:8; Deut 32:14) like wine (vv. 3–4, cf. v. 7).[4] Given such aggression, the city is in danger of being “intoxicated”, i.e., of suffering military defeat. Granted, the rhetoric of instability in vv. 3–4 could be understood as representing the waters, earth, and mountains as being intoxicated themselves, while they are trying to intoxicate the city and its residents.[5] This, however, would be an overinterpretation of the images in vv. 3–4. The instability of hostile forces in vv. 3–4 indicates their tumult and aggression against the city, and anticipates their defeat (cf. vv. 7, 9–11). Their "intoxication" is properly articulated in vv. 7, 9–11, where "intoxication" imagery (losing balance and falling down, v. 7) gradually gives way to and is superseded by more overt imagery of military defeat (vv. 9–11, on which see Section II). This move from more figurative representation of military aggression (i.e., via intoxication imagery) to more overt/literal representation of military action (i.e., as terminating wars and destroying implements of war, vv. 9–11) parallels the move from more figurative representation of enemies (i.e., as the waters, earth, and mountains, vv. 3–4) to their more literal depiction (i.e., as the nations and kingdoms, vv. 7, 9–11) later in the psalm. In sum, in Psalm 46, the figurative rhetoric decreases as the "narrative" progresses, but the literal language increases. The overlap in terminology between the two (e.g., raging, falling in vv. 3–4 and 7) is needed to bind the two together and keep the overall story line cohesive and poignant.

Section II: “Intoxication” of the City and the Nations. In section II, despite its opponents' efforts, the city is supported by God (v. 5–6) and stands (בל־תמוט [v. 6]). Part of its survival is due to the presence of the river and its streams, which “gladden” the city as good wine.[6] Since ancient canal systems supplied water to cities and were part of their defensive structures (The River and Its Streams in Psalm 46), the presence of the river in v. 5 ensures the city's defense and survival. By contrast, the city's attackers are said to totter and fall down (מוט [v. 7]; cf. vv. 9–10), presumably in “drunken stupor” (cf. Hab 2:15–16; Ps 75:8; Zech 12:2, 3; cf. תמוט רגלם [Deut 32:35] in wine and judgment related context [Deut 32:23–33, cf. v. 14]).

Effect

The effect of this feature is to employ the imagery of intoxication to create an ironic reversal throughout the psalm. The efforts of the nations to intoxicate the city and its residents are in vain. YHWH protects them (v. 6), gladdens them as if with good wine (v. 5), and instead intoxicates the nations (vv. 9–10) with the cup of his wrath.

Chiastic Structures: God's Support and Protection

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

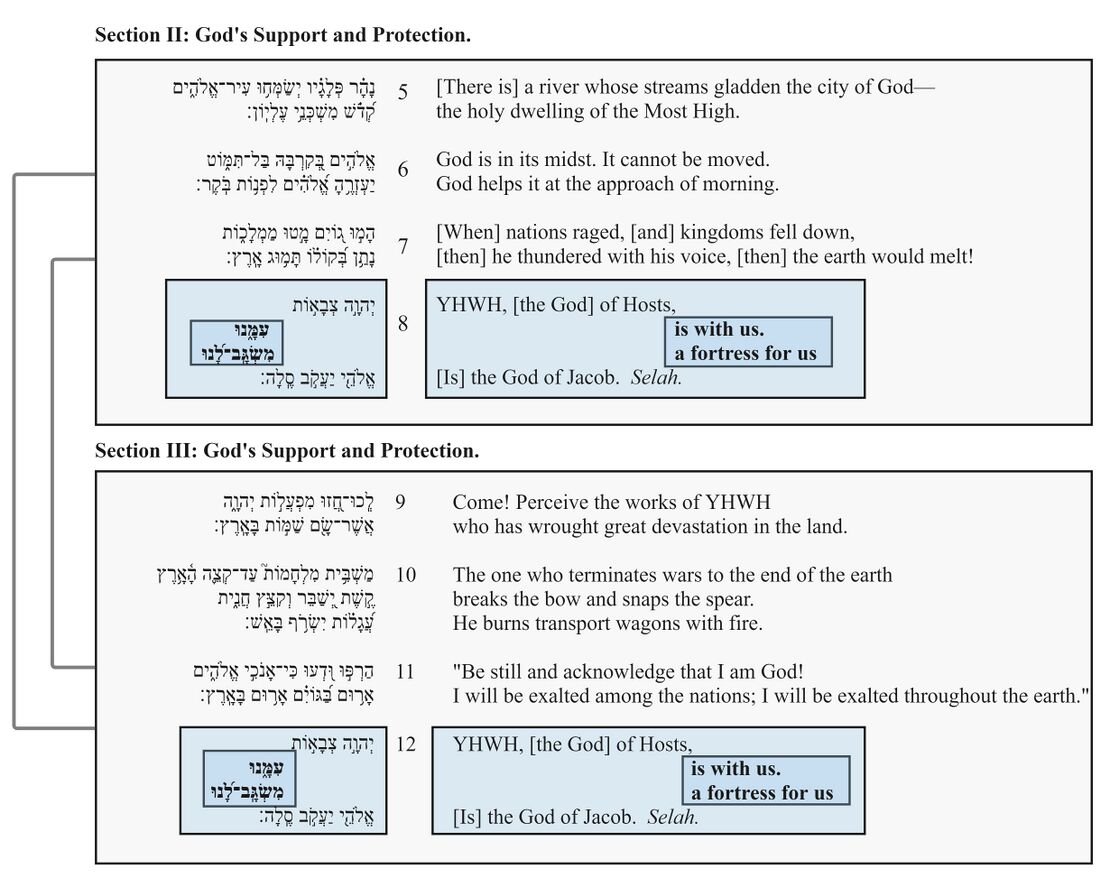

Sections II and III (vv. 5–7 and 9–11) are followed by the refrain, YHWH, [the God] of Hosts, is with us. The God of Jacob is a fortress for us (vv. 8, 12). This refrain has a symmetric word order (a.b|b’.a’).[7] In it, in the second clause (v. 8b, v. 12b), a fortress for us (משגב־לנו) is fronted to create a chiasm with the first clause (v. 8a and v. 12a).

Effect

As previously noted, Psalm 46 can be divided into three sections, and each section highlights God’s power to sustain and protect his people in the most adverse of circumstances, i.e., warfare. Given the multitude of the enemy forces (nations and kingdoms, v. 7) and the magnitude of their military might (cf. vv. 3–4), God’s ability to protect his people is their only chance for survival. Accordingly, in the refrain, God’s role in relation to his people under attack is emphasized through chiastic arrangements of clause constituents in vv. 8 and 12—i.e., God is his people’s fortress. Through such chiastic arrangement, the psalm centers the benefits of God’s presence in his people’s lives. Given the context of warfare, these benefits literally equal their physical survival.

Repeated Roots

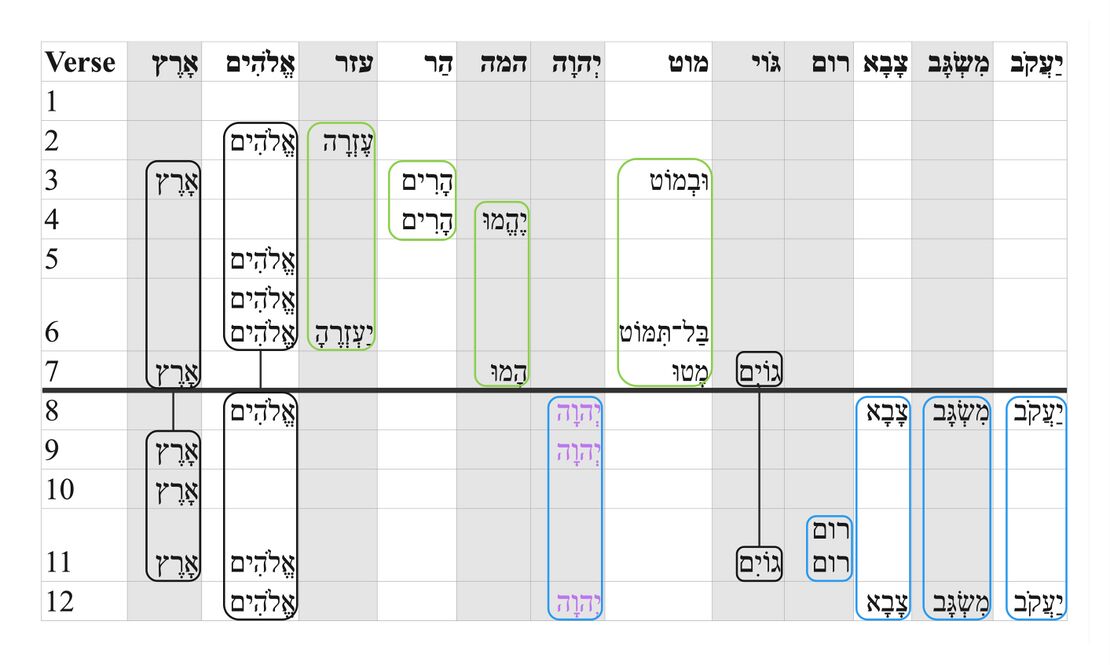

The repeated roots table is intended to identify the roots which are repeated in the psalm.

| Repeated Roots legend | |

|---|---|

| Divine name | The divine name is indicated by bold purple text. |

| Roots bounding a section | Roots bounding a section, appearing in the first and last verse of a section, are indicated by bold red text. |

| Roots occurring primarily in the first section are indicated in a yellow box. | |

| Roots occurring primarily in the third section are indicated in a blue box. | |

| Roots connected across sections are indicated by a vertical gray line connecting the roots. | |

| Section boundaries are indicated by a horizontal black line across the chart. | |

Notes

The repetition of various roots in Psalm 46 can be said to have a structural and exegetical significance. On the one hand, through their repetition, various lexemes create a tight correlation between the strophes of the Psalm. On the other, they dictate how we interpret various entities within this composition.

- The term “earth/land”/אָרֶץ appears in all three strophes (vv. 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, and 11). Such distribution of the term holds the strophes of the psalm together. Additionally, these occurrences indicate the universal scope of God's influence and his universal exultation.

- The repetition of verbal roots in strophes 1 and 2 (vv. 2-4 and 5-7) connect the forces of nature and the nations/kingdoms of world. Just as in vv. 3–4, the waters rage (חמה) and mountains move/fall (מוט), in v. 7, the nations rage (חמה) and the kingdoms move/fall (מוט).

- Other roots link the 2 strophes together, calling for the correlation between the waters and the nations. In v. 2, God is an easily accessible help (עזרה), and in v. 6, he will help (עזר) the city under attack. So the two domains--that of nature/cosmos and history--are brought together, and one domain (nature/cosmos) stands for the other (history).

- The term אֱלֹהִים/Elohim appears seven times in the psalm (vv, 2, 5, 6 [x2], 8, 11, and 12). Mostly, representing protection, security, and stability.

- The name יְהוָה is also repeated (vv. 8, 9, and 12), but it is found at the end of Strophe 2 and in Strophe 3, both of which are militaristic in focus.

- Notably, in vv. 8 and 12, יְהוָה is paired up with the "Hosts/Armies" (appearing twice) which is a proper militaristic name for God.

Given such distribution of terms, and commenting on the inter-relatedness between the strophes, P. Cragie notes that Psalm 46 speaks of God protecting people in different circumstances: "God’s refuge in the context of natural phenomena (vv 2–4); God’s refuge in the context of the nations of the world (vv 5–8); God’s refuge in the context of both natural and national powers (vv 9–12)."[8] Based on its repeated roots, the psalm can be summarized as follows:

- ↑ Wright 2015: 148.

- ↑ A tell is a mound, made up of the remains of a succession of previous settlements.

- ↑ Cf. Prov 20:1, which “implies the effect or influence of wine-drinking or wine itself, [the verb המה] probably presupposes the physical nature of wine, i.e. the raging state of foaming wine” (Tsumura 1981: 171). Cf. “to be boisterous, turbulent” as with wine (Zech 9:15).

- ↑ The verb חמר/"to foam/ferment” (v. 4) reflects the “process by which liquids form small bubbles, due to agitation or fermentation -- to foam” (SDBH; cf. “to ferment, boil, or foam up”; BDB; HALOT). Hence in Ps 46:4, the image associated with the raging, chaotic waters reflects the fermenting process in the production of wine and beer (cf. Ps 75:8; Deut 32:14) (Tsumura 1981: 167–170).

- ↑ Per discussion in The Raging Waters in Psalm46:2-4, the enemy forces in section 1 are represented by the waters alongside the earth and the mountains. For example, W. Brown argues that in this Psalm, the cosmic/natural forces such as the raging waters and quaking mountains are “mapped” onto the turbulence and instability experienced in the political realm. Hence, on a metaphoric level, the image of raging, foaming waters signifies the raging, hostile nations (Brown 2002: 116). Regarding the use of "earth" and its constituent elements (mountains, as well as waters) in Psalm 46, Kelly in turn notes that, "on the one hand, in vss. 2–6 ʾereṣ along with the mountains and waters is presented as participating in a chaotic tumult which is contrasted with the peaceful stability of the city of God; on the other hand, in vs. 11 (or vss. 9–11) ʾereṣ is presented as corresponding in nature to the city. The transition from the tumult of 'eres to her peace is accomplished in vs. 7" (Kelly 1970: 306). He further notes that, "Commentators have commonly pointed to the synonymous parallelism between vss. 3–4 and vs. 7: the shaking [...] of the mountains in vs. 3b and the roaring [...] of the waters in vs. 4a parallel the shaking [...] of the kingdoms and the roaring [...] of the nations in vs. 7a. As the actions of the nations and kingdoms may be understood as synonymous expressions for political disorder, so the actions of the mountains and waters may be understood as synonymous expressions for cosmic disorder; this is supported by their apparent parallel use in vs. 4. In turn, the activity of ʾereṣ in vs. 3a appears to parallel the tumult of the mountains in vs. 3b, and this suggests that the activity of ʾereṣ is also to be understood as paralleling the disorder of the nations/kingdoms" (Kelly 1970: 306, 307). "This conclusion is supported by the parallelism in vs. 11b where Yahweh declares his victorious exaltation with respect to [...] the nations and ʾereṣ. In turn, the parallelism of vs. 11b suggests that ʾereṣ in 7b is a cosmic image for the nations/kingdoms of 7a; thus, the political disorder is overcome and quieted in terms of the melting [...] of ʾereṣ. Indeed, vs. 11 may be considered an explication of the theophanic rebuke in vs. 7b" (Kelly 1970: 307).

- ↑ Tsumura 1981: 172.

- ↑ Raabe 1990: 59; van der Lugt 2010: 50.

- ↑ Craigie 1983: 323.