Psalm 119 Poetics

About the Poetics Layer

Exploring the Psalms as poetry is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language. This layer is comprised of two main parts: poetic structure and poetic features. (For more information, click 'Expand' to the right.)

Poetic Structure

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into sub-sections, sub-sections into larger sections, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

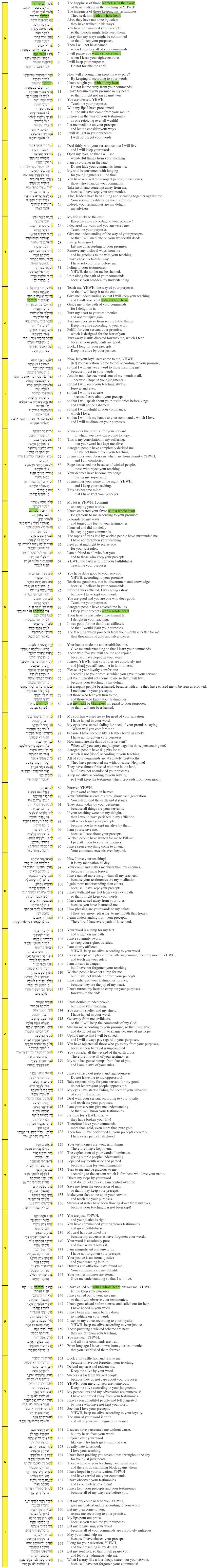

Poetics Visuals for Psalm 119

Poetic Structure

Poetic Macro-structure

Notes

- YHWH addressed in 2nd person in v. 4 breaks pattern of 3rd person throughout vv. 1-3. "In this sense, the concluding verseline of Canticle I.1 paves the way for the following unit" (van der Lugt 2013, 300).

- Note that out of 8 bicola in the א stanza, four of them begin with בְּ in the B-line, perhaps thereby priming the next stanza.

- Note that v. 3 is one of only three verses in the psalm without one of the Big Eight Torah words (see also vv. 90, 122). At least in the case of v. 3 and 90, there is probably a structural motivation behind the absence (being the beginning of the first and second halves of the psalm).

- For the similar beginnings, compare the generic 3rd person in vv. 1-3 and v. 9, described as 'blameless in their way' (תְמִֽימֵי־דָ֑רֶךְ) and 'keeping his way pure' (יְזַכֶּה ... אֶת־אָרְח֑וֹ), respectively. Furthermore, the psalmist describes the happy ones who seek YHWH (לב כלב דרשׁ) in v. 2, and now the counts himself among them (v. 10).

- There are similar midpoints in the use of אַתָּה as subject (most commonly pronominally-suffixed ךָ throughout the psalm) in vv. 4, 12 (elsewhere only in v. 68, 102, 114, 137, 151).

- Note: stanza #3 has no mention of דֶּרֶךְ or אֹרַח (the former to return in a big way in stanza #4; the latter not until v. 101).

- Stanza #3's inclusio of עַבְדְּךָ and the variation on דבר probably sets up the 'word' defense against the psalmist's antagonists (cf. the pattern in vv. 42, 43 and 46).

- For temporal adverbs as fitting closure for the strophe, cf. vv. 44 and 52, which prime their structural and thematic importance for the psalm as a whole (see note below on v. 89).

- v. 22: For the revocalization גֹּל, see the Grammar note (MT: גַּל).

- On stanza #3's inclusio (vv. 23): Since the final line of many of the stanzas simply summarise or conclude the content, "the seventh verse in each strophe acquires a prominent significance" (Zenger 2011, 261). See also דבק in vv. 25, 31; זכר in v. 55; שׁמר in v. 63; טֽוֹב־לִ֥י in v. 71; כִּלּ֣וּנִי in v. 87; מָה in v. 103; אָהַבְתִּי in vv. 119, 127; עַל־כֵּ֭ן in v. 127; רְ֭אֵה and חַיֵּֽנִי in v. 159; and the jussive תְּֽחִי in v. 175.

- v. 33-40: "This strategic placement [of חַיֵּנִי] demarcates the substanza (vv. 37-40), with the paradoxical result that the first substanza no longer needs a powerful structure" (Fokkelman 2003, 241); though see the mini chiasm in vv. 33-34 and the waw-pattern beginning the B-lines throughout vv. 33-34, 36 and conspicuously abandoned in vv. 37-40.

- v. 37: For the emendation כִּדְבָרְךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: בִּדְרָכֶ֥ךָ).

- v. 44: For a similar function of temporal adverbials for good closure of a strophe, see also v. 20 and the מֵעוֹלָם of v. 52. However, we do not get another לְעוֹלָם until v. 89, the mid-point (and turning point) of the psalm. (Notice that v. 44 is the half-way point to this transition).

- v. 52, 55: Note that both verses begin with 1sg qatal זָכַרְתִּי followed by a wayyiqtol, which is quite rare in the psalm (see also vv. 26, 59, 106, 131, 147, 158, 163, 167). This final זָ֘כַ֤רְתִּי in the stanza, appearing in the seventh verse, provides an apt verbal inclusio.

- v. 57, 61: In the similar beginnings provides by חֶלְקִ֖י and חֶבְלֵ֣י, we have both semantic contrast and phonetic similarity. See also Deut. 32.9 and Ps 16.5-6 for the word pair חֶלֶק and חֶבֶל, though in both positive connotations in those instances (as noted in van der Lugt 2013, 308).

- vv. 57-64: The mention of חֶלְקִ֖י at the beginning of v. 57 sets the tone for the entire ח-stanza, culminating in the mention of הָאָ֗רֶץ in v. 64. Despite the enemies' traps potentially restricting the psalmist's feet (v. 61), he 'turns' them to YHWH's testimonies (v. 59). The use of חֲצֽוֹת (v. 62) may also hint at spatial restriction: 'half' (Fokkelman 2003, 245), or at least the inclusion of both time and space (Auffret 2006, 23).

- The story of שׁמר throughout the stanza evolves from 'I planned to do so' (v. 57) to 'I rushed to do so' (v. 60), to 'I'm not the only one' (v. 63). The fact that there are others who שֹׁמְרֵ֗י פִּקּוּדֶֽיךָ is proof that חַסְדְּךָ֣ יְ֭הוָה מָלְאָ֥ה הָאָ֗רֶץ (v. 64) within the frame of texts like Josh. 14.5: כַּאֲשֶׁ֨ר צִוָּ֤ה יְהוָה֙ אֶת־מֹשֶׁ֔ה כֵּ֥ן עָשׂ֖וּ בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל וַֽיַּחְלְק֖וּ אֶת־הָאָֽרֶץ׃ and in light of the parallels between 'Israel', the 'house of Aaron' and 'fearers of YHWH in Pss 115.9-11 and 118.2-4. Thus, "the hymn [v. 64a] fittingly concludes the canto as a whole" (van der Lugt 2013, 308).

- v. 64: Out of six instances of this expression (see vv. 12, 26, 64, 68, 124, 135), v. 124 is the only other case with the order וְחֻקֶּ֥יךָ לַמְּדֵֽנִי.

- vv. 64, 67, 71: For the significance of root ענה see also v. 75, below. For significance of למד חק throughout the psalm see vv. 12, 26, 64, 124, 135, 171. Furthermore, it is "remarkable that 68b is identical with 12b and 124b, at exactly the same distance of 56 verses" (Fokkelman 2003, 247), which may have numerical significance as the multiple of seven and eight.

- vv. 71-72: On the double טוֹב לִי in these two verses as closure of the stanza, see also the double גָּם in vv. 23-24 and double עַל כֵּן in vv. 127-128.

- vv. 75–76, 86, 88: While חֶסֶד is slightly more common throughout the psalm (seven times: twice here and otherwise vv. 40, 64, 124, 149, 159), אֱמוּנָה only occurs five times: twice here, soon after (v. 90) and otherwise vv. 30 and 138. In both cases, these two instances could be considered central (two preceding and three following in the case of חֶסֶד; one preceding and two following in the case of אֱמוּנָה).

- vv. 73-80: For the symmetry between these two strophes, note the mention of YHWH fearers in vv. 74, 79, followed by the root ידע in vv. 75, 79 and יְהִי in vv. 76, 80 for similar endings.

- vv. 77-80: The initial jussives in every verse of this stanza differentiates it from the preceding, with only the יְהִי of v. 76.

- vv. 81-88: The כ–stanza has been characterized as 'by far the most desperate' (Soll 1991, 100), hitting a record low before the poignant transition into the heights of vv. 89-112!

- Discontinuity: "Except for the norm [Torah] words, Kaph and Lamed have few expressions in common." (Fokkelman 2003, 249).

- Similarities with א-stanza: Absence of "I" phrases in vv. 89-91 and vv. 1-3 (see participant analysis) and two of the only three verses in the psalm lacking one of the Big Eight (vv. 3, 90) along with v. 122.

- vv. 89ff: The temporal adverbs, especially prevalent in this stanza yet taking a central role throughout the remainder of the psalm, have been bolded. Notice the previous instances of לְעוֹלָם falls exactly half way up to this point (v. 44), and is picked up again at the end of the צ–stanza in vv. 142, 144; the end of the ק–stanza in v. 152; and at the end of the ר–stanza in v 160. Thus the delimitation of the ל, מ and נ–stanzas as structurally central and forming a thematic interlude between the first and section larger sections (vv. 1-88 and 113-160, respectively). Similarly, the final two stanzas form a structural conclusion to the poem.

- Regarding the central division of the psalm, cf. Lubaschagne's position that the psalm contains a "menorah pattern" (2012, 1), though he selects the middle four stanzas, purely on numerical basis.

- vv. 92, 95: Outside of the present stanza, the root אבד is only found in v. 176, another enclosed section.

- Continuity: "it looks as if the close link forged between Lamed and Mem at the start of the second series of eleven octets is the counterpart to and parallel of the connections between Aleph and Beth at the start of the first series" (Fokkelman 2003, 250). I would include the נ–stanza, however. Besides those elements indicated on the visual, see also the repetition of hithpolel בין in v. 95 before vv. 100, 104.

- v. 98: For the revocalization מִצְוָתֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִצְוֺתֶ֑ךָ).

- The contrast formed by the love/hate inclusio in the מ–stanza primes the structure of the following canto, vv. 113-128. See also the use of עַל־כֵּן in v. 104, replicated by the closure in vv. 127-128 (and even as a pivot in v. 129); מִדְּבַ֥שׁ לְפִֽי in v. 103b followed by מִזָּהָ֥ב וּמִפָּֽז in v. 127b; and שָׂנֵ֤אתִי ׀ כָּל־אֹ֬רַח שָֽׁקֶר in v. 104 followed by כָּל־אֹ֖רַח שֶׁ֣קֶר שָׂנֵֽאתִי in v. 128 (Fokkelman 2003, 254-255).

- vv. 113-120: In a stanza of contrasts, the following can be discerned:

- 'the double-minded' and 'your law' (v. 113)

- 'the double-minded' and 'my shelter and shield' (vv. 113-114)

- 'evildoers' and 'my God' (v. 115)

- 'evildoers' and 'my hope' (vv. 115-116)

- the psalmist and 'those who go astray' (vv. 117-118), especially in their relation to חֻקֶּיךָ

- 'the wicked of the earth' and the psalmist (vv. 119-120)

- The result: the objects of the psalmist's love and hate are clear. Furthermore, it is YHWH's word that he fears, not the wicked.

- v. 119: For the emendation חָשַׁבְתָּ, see the Grammar note (MT: הִשְׁבַּ֥תָּ).

- vv. 122, 124, 125: The fairly common self-identification as עַבְדְּךָ has not been used since v. 84, and is now repeated three times in the present stanza.

- v. 128: For the emendation פִּקּוּדֶיךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: פִּקּ֣וּדֵי כֹ֣ל).

- vv. 129-144: Though forming part of a new section, made transparent by the love/hate inclusios throughout vv. 113-128, this third instance of עַל־כֵּן provides a handy pivot from vv. 127-128. Similar traces include another use of the root אהב in לְאֹהֲבֵ֥י שְׁמֶֽךָ (v. 132), 'the oppression of man' (מֵעֹ֣שֶׁק אָדָ֑ם; v. 134) and בְּעַבְדֶּ֑ךָ (v. 135). Furthermore, see the note on לְעוֹלָם below, at vv. 142, 144.

- The structural principle of the פ and צ stanzas then, seems to be primarily the exclusion from quite clear structural signs otherwise: most saliently, the אהב/שׂנא contrast closing vv. 113-128 and the לְעוֹלָם initiating the final line of vv. 152 and 160. See, however, the inclusio with the verbless predication concerning עֵדוֹתֶיךָ and the verb hiphil בין.

- v. 137: For the emendation מִשְׁפָּטֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִשְׁפָּטֶֽיךָ).

- vv. 137-144: On the similar structure of these two strophes, see the mention of צַדִּיק/צְדָקָה related to YHWH, the second verse containing צֶדֶק in the A-line followed by the root אמת in the B-line, as well as צר in the third verse.

- vv. 142, 144: Note the continued importance of לְעוֹלָם throughout the psalm, here repeated, though line-final. Its contribution in the following two stanzas provides similar endings, occurring as the first major constituent in the final line of each. It may be the case that the twofold repetition here primes the audience for the following two in vv. 152 and 160.

- v. 143: Notice the repetition of מצ involves the theme letter of the stanza (צ), even though not necessary for the structure.

- vv. 161-176: In light of the conclusive לְעוֹלָם in v. 160 (see the notes on vv. 89ff concerning its structural significance throughout the psalm) and the internal cohesion of this section (see, e.g., the threefold repetition of הלל), this turn in praise represents a break from the rhythm of the poem established up to this point, and has thus been deemed structurally discontinuous, forming a conclusion to the psalm as a whole.

- vv. 163, 167: Note that the final instance of שׂנא is augmented by the hendiadys with תעב: really hate (see phrase-level notes) and the final אהב uniquely accompanied by מְאֹד.

- vv. 164, 171, 175: These are the only three instances of the root הלל in the psalm, all reserved for the final canto!

- Continuity: besides the repetition of the root הלל in vv. 164, 171 and 175, the B-line of v. 164 is almost identical to the B-line of v. 172 (מִשְׁפְּטֵ֥י צִדְקֶֽךָ in the former; מִצְוֺתֶ֣יךָ צֶּֽדֶק in the latter).

- For the thematic continuity in the alternation throughout the ת–stanza, see van der Lugt (2013, 324-325). He only implicitly hints, however, at the exclusion of v. 176 from this pattern, which therefore sets this verse off from its stanza in terms of relative salience.

- Similar structure: Each strophe contains a plea (vv. 169-170 // 173-174) followed by praise (vv. 171-172 // 175-176). Note also that the repetition of the root הלל in vv. 171 and 175 are both found in the fifth line of their respective strophes.

- Macro-inclusio?: Whybray observes, "In v 174-76, finally, there was apparently an attempt to round off the whole psalm by referring back to the initial verses of the psalm proper (v 4-6)." (1997, 42).

- General observations:

- "We need not spend much thought on the textual units on the level above the strophe" (Fokkelman 2003, 235).

- "Since there is little consensus among scholars about the poem’s structure in terms of content, in my judgement, the only approach that will open new perspectives, is to focus primarily on the formal aspects of the text, more specifically on the numerical factors" (Lubaschagne 2012, 3).

- "Associative sequences do have an impact on interpretation, especially of individual verses, but they do not necessarily amount to a structuring principle" (Reynolds 2010, 21).

- "There is much more thematic consistency of theme and sense within individual stanzas than has been commonly supposed. Indeed, some sections have quite definite sequences of thought" (Whybray 1997, 41).

- "My conclusion is that psalm 119 is anything but a collection of more or less disconnected sayings about the Torah. As a matter of fact, one needs a bird's-eye view of the composition to grasp the mutual relationships between distant sections" (van der Lugt 2013, 343).

- Structural observations:

- The standard understanding of each stanza's division into two sets of four verses is followed consistently by Auffret (2006) and van der Lugt (2013). Fokkelman (2003, 236) offers only a few exceptions (the aleph, zayin and lamed stanzas). This structure has been confirmed by my own analysis here.

- The macro-relationship between the stanzas have been suggested by previous scholarship as:

- Stanzas I-II (vv. 1-16) as the Introduction; stanzas III-XII (vv. 17-96) as Part 1 and stanzas XIII-XXII (vv. 97-176) as Part 2 (van der Lugt 2013, 332). "I further assume that, subsequently, both main parts divide into three subsections, consisting of 4, 4 and 2 cantos respectively... Although there are all kinds of thematic and formal relationships between these sections, there is a special structural correspondence between the Introduction (Cantos I-II) and the 'twin-cantos' concluding Parts I and II" (ibid.), that is, vv. 81-96 and vv. 161-176. I agree with the structural significance of the Introduction as vv. 1-16 and the conclusion as vv. 161-176. I differ, however, in my understanding of the semantic and thematic center of the psalm (vv. 89-112) as highly significant at its midpoint (cf. also the observations of Lubaschagne 2012,1; the notes at v. 89ff, and Fokkelman 2003, 250, who observes the similar continuity between the ל and מ stanzas that we have between the א and ב stanzas.). In general, I also agree with van der Lugt concerning the pairing of stanzas as 'twin-cantos' (with the exceptions of vv. 49-72 and 89-112).

- Auffret claims that Stanzas 1-11 form Part 1, in chiastic fashion with stanza 6 in the center, while stanzas 12-22 form Part 2 in chiastic fashion with stanza 18 in the center (2006, 233). Again, it seems that Part 2 (vv. 89ff.) does indeed form a new beginning. The concentric pattern of each half of the psalm, however, is slightly forced and based on little evidence.

Line Division

- v. 9: Current division as Aleppo, Sassoon, Or 2373, JTS 680. Leningradensis breaks between בַּמֶּ֣ה יְזַכֶּה־נַּ֭עַר // אֶת־אָרְח֑וֹ לִ֝שְׁמֹ֗ר כִּדְבָרֶֽךָ.

- v. 22: For the revocalization גֹּל, see the Grammar note (MT: גַּל). No pausal forms, major disjunctive accents, clause boundaries or prosodic word counts are affected.

- v. 23a contains 5 prosodic words, but only nine syllables, just as the B-line (unless the vocal shewa in עַ֝בְדְּךָ֗ is counted, in which case the B-line has ten syllables). Freedman and Geoghegan consider this verse to be a tricolon (1999: 22), as they do vv. 39, 43, 48, 62, 63, 69, 75, 78, 145, 169 and 176, though noting, "Some of our tricola-line conjectures are more persuasive than others, but a reasonable case can be made for at least half (6) of them" (ibid.).

- The (5-3) bicolon is found in Rahlfs', CUL: T-S A13.46, Fr 1r, almost certainly Sinaiticus and Leningradensis (though with space constraints), Aleppo, Sassoon, Or 2373 and JTS 680.

- v. 37: For the emendation כִּדְבָרְךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: בִּדְרָכֶ֥ךָ). No pausal forms, major disjunctive accents, clause boundaries or prosodic word counts are affected.

- v. 48: Fokkelman (2003, 235) prefers a tricolon here; in both Leningradensis and Aleppo it is difficult to tell due to space constraints, but JTS 680; Or 2373; CUL T-S A13 49 (1v) contain bicola.

- v. 52: The 4-1 is found in Rahlfs, Leningradensis, CUL TS A-13 49 (1r); Or 2373.

- Aleppo seems to indicate a division between מֵעוֹלָ֥ם and יְהוָ֗ה; Sassoon groups מֵעוֹלָם יְהוָה וָאֶתְנֶחָם together, while JTS 680 has יְהוָה וָאֶתְנֶחָם as the B-line.

- Sinaiticus places ἀπʼ αἰῶνος after the vocative, κύριε, and thus in a second line, though evidently still belonging to the first clause:

- ἐμνήσθην τῶν κριμάτων σου κύριε

- ἀπʼ αἰῶνος καὶ παρεκλήθην

- Grosser understands "a clear one-word line" to emerge here (2023: 259) and draws parallels with v. 46b (וְלֹ֣א אֵבֽוֹשׁ׃), which, under other circumstances, may very well have been conjoined by a maqqef.

- v. 98: For the revocalization מִצְוָתֶ֑ךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִצְוֺתֶ֑ךָ). No pausal forms, major disjunctive accents, clause boundaries or prosodic word counts are affected.

- v. 119: For the emendation חָשַׁבְתָּ, see the Grammar note (MT: הִשְׁבַּ֥תָּ). No pausal forms, major disjunctive accents, clause boundaries or prosodic word counts are affected.

- v. 128: For the emendation פִּקּוּדֶיךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: פִּקּ֣וּדֵי כֹ֣ל). No pausal forms, major disjunctive accents or clause boundaries are affected. The prosodic word count in this bicolon would be distinct from the MT, however, as 3-3 instead of 4-3, which is less natural to Psalm 119, almost every bicola of which has a longer first line than second. In any case the resulting syllable count is still 10-8.

- v. 137: For the emendation מִשְׁפָּטֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִשְׁפָּטֶֽיךָ). The MT's silluq has been removed, and the pausal form מִשְׁפָּטֶךָ has been posited. No clause boundaries or prosodic word counts are affected, however.

- v. 145: proposed as a tricolon by Soll (1991, 106); Freedman and Geoghegan (1999, 22); Fokkelman (2003, 235).

- The bicolon is found in Aleppo, Rahlfs, Sinaiticus, Leningradensis; Sassoon; CUL T-S A13 41 (4v); Or 2373.

- v. 149b: On the somewhat unexpected pausal form כְּֽמִשְׁפָּטֶ֥ךָ, the Babylonian manuscripts JTS 631 and 680 and Or 1477 read a plural; only Or 2373 lacks the mater yod.

- v. 175b: Note that the "pausal form" on וּֽמִשְׁפָּטֶ֥ךָ should simply be taken as a plural, lacking the plene yod. All the Babylonian manuscripts provide the yod here, and Or 1477 even has the waw in יעזרוני for the OHSB's יַעֲזְרֻֽנִי.

- v. 176 is only the second instance of 5 prosodic words (cf. v. 23)!

- Rahlfs' LXX is split between two lines (3-6):

- ἐπλανήθην ὡς πρόβατον ἀπολωλός·

- ζήτησον τὸν δοῦλόν σου, ὅτι τὰς ἐντολάς σου οὐκ ἐπελαθόμην.

- Sinaiticus, however, indicates either a tricolon or the MT's line division, forced into three due to space constraints:

- ἐπλανήθην ὡς πρόβατον ἀπολωλός·

- ζήτησον τὸν δοῦλόν σου,

- ὅτι τὰς ἐντολάς σου οὐκ ἐπελαθόμην.

- Aleppo may have intended a tricolon; Leningradensis is hard to tell, though looks to favor continuity, despite space constraints.

- The bicolon is evident in JTS 680 and Or 2373.

- Fokkelman (2003, 235) prefers a tricolon here, probably in light of the five prosodic words (but see also v. 23), but more explicitly because there are three clauses, the first two asyndetic, which is also not unique here (see vv. 17, 57, 94, 125, 145-146). Of course, he proposes the same thing for v. 145, but not 146, so his main criterion seems to be the number of prosodic words.

Poetic Features

1.From Aleph To Taw

- **v. 22: For the revocalization גֹּל, see the Grammar note (MT: גַּל).

- **v. 37: For the emendation כִּדְבָרְךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: בִּדְרָכֶ֥ךָ).

- **v. 98: For the revocalization מִצְוָתֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִצְוֺתֶ֑ךָ).

- **v. 119: For the emendation חָשַׁבְתָּ, see the Grammar note (MT: הִשְׁבַּ֥תָּ).

- **v. 128: For the emendation פִּקּוּדֶיךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: פִּקּ֣וּדֵי כֹ֣ל).

- **v. 137: For the emendation מִשְׁפָּטֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִשְׁפָּטֶֽיךָ).

Feature

Psalm 119 consists of 22 stanzas, representing each letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Each stanza has eight verses (see poetic feature, Big Eight). Each verse is a bicolon and the first line begins with the thematic letter of its respective stanza: aleph from vv. 1-8, bet from vv. 9-16, etc., until taw from vv. 169-176.

Effect

The structure of the full acrostic–not lacking any letter–indicates the comprehensive treatment of the subject matter of the psalm: YHWH's word in the life of the psalmist. Specifically, it contributes to the message of the sufficiency and completion of YHWH's word, and so "the praise of tôrat yhwh" (Freedman 1999, 88; for "completion" as iconic of the acrostic, see James 2022, 324 n. 17 and the sources cited therein).

The specific function of the acrostic pattern in Ps 119 also provides order in the evidently tumultuous circumstances of the psalmist's experience (Freedman 1999, 93), such that he is at least trying, through the form of the psalm, to make sense of the message of his prayer (similar to the function of the book of Lamentations, though seemingly on an individual level).

Finally, it may also hint at the required integrity of the psalmist's response (see, e.g, the use of the phrase בְכָל־לֵב "with a whole heart" in vv. 2, 10, 34, 58, 69, 145; בְּיֹ֣שֶׁר לֵבָ֑ב "with a sincere heart" in v. 7; יְהִֽי־לִבִּ֣י תָמִ֣ים "let my heart be blameless/complete" in v. 80 and the very first verse: אַשְׁרֵ֥י תְמִֽימֵי־דָ֑רֶךְ "the happiness of those blameless/complete (in their) way".

2.The Big Eight

- **v. 22: For the revocalization גֹּל, see the Grammar note (MT: גַּל).

- **v. 37: For the emendation כִּדְבָרְךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: בִּדְרָכֶ֥ךָ).

- **v. 98: For the revocalization מִצְוָתֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִצְוֺתֶ֑ךָ).

- **v. 119: For the emendation חָשַׁבְתָּ, see the Grammar note (MT: הִשְׁבַּ֥תָּ).

- **v. 128: For the emendation פִּקּוּדֶיךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: פִּקּ֣וּדֵי כֹ֣ל).

- **v. 137: For the emendation מִשְׁפָּטֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִשְׁפָּטֶֽיךָ).

Feature

As each stanza contains eight bicola, Psalm 119 is also dominated by eight "Torah words" (see, among others, Freedman 1999, 30; Soll 1991, 35-56; Reynolds 2010, 16):

- – אִמְרָה (x19)

- – דָּבָר (x23)

- – חֹק (x22)

- – מִצְוָה (x22)

- – מִשְׁפָּט (x23)

- – עֵדוּת (x23)

- – פִּקּוֹדִים (x21)

- – תּוֹרָה (x25)

[Note: A minority of scholars (see, e.g., Snearly 2015: 131-132) have followed the Masorah's note at v. 122 in postulating ten words, with the inclusion of דֶּרֶךְ and אֱמוּנָה (available at https://mg.alhatorah.org/Dual/Minchat_Shai/Tehillim/119.103#m7e0n6; כל אלפא ביתא אית בכל פסוק חד מן עשר לישני אלין. אמירה. דבור. עדות. דרך משפט. פקוד. צווי. תורה. חק. אמונה.]

These 8 key words relate to YHWH's word, typically with a 2ms pronominal suffix, and are distributed across the psalm using three different patterns. In the vast majority of the 176 verses, there is only one of the eight words per verse. However, there are four verses [3, 90, 121-122] where none of the eight words appear, and there are five verses where two of the eight words appear.

The words are more or less equally distributed across the two halves of the psalm (Freedman 1999, 35), occurring in every verse except vv. 3, 90 and 122 (Freedman does not account for the fact that מִשְׁפָט in v. 121 is carried out by the psalmist). The absence in v. 3 coincides exactly with the close of a participant shift in v. 3 (see participant analysis) and that of v. 90 falls in the second verse of the poetic section vv. 89-112. Both occur near the beginning of the two halves of the psalm. Vv. 16, 48, 160, 168, 172, which are the final verses in the ב, ו, ר, ש–stanzas, and the end of the first half of the ת–stanza, contain two of them. Their pattern concludes larger units (א–ב, ה–ו) and exhibits somewhat of a cluster towards the end of the psalm.

This results is a total of 178 instances of the Big Eight, remarkably close (but not exactly) to the numbers of verses in the psalm (176).

Note: the generic וְאֶֽעֱנֶ֣ה חֹרְפִ֣י דָבָ֑ר in v. 42, דְבַר־אֱמֶ֣ת in v. 43, and the psalmist's עָ֭שִׂיתִי מִשְׁפָּ֣ט in v. 121 are excluded from the count.

Effect

If the form of the acrostic provides a sense of order and completion in relation to YHWH's word and the psalmist's relationship to it, the inexact application of the Big Eight–not occurring once in each verse, which was conceivably a possibility–maintains a level of frustration, parallel to the psalmist's circumstances as he seeks out the desired order and completion (Freedman 1999, 93).

At the same time, the Big Eight also contribute to the sense of inauguration of new beginnings as a highly salient concept in the number eight: the seven of creation plus one. For example, the Levites were commissioned for duty on the eighth day after the completion of the tabernacle (Lev 9:1), while the celebration of the temple inauguration lasted eight days (1 Kgs 8:66), as did the second temple inauguration (Neh. 8.1-18; see Zenger 2011, 257-258 for discussion). Not only did the 7+1 inaugurate the enjoyment of the new creation after resting on the seventh day, such that cosmic frustration was defeated in the order of YHWH's creation (vv. 89-91). In this psalm, after going astray and being afflicted (see, e.g., v. 67) the psalmist launches his new commitment to faithfulness (v. 16). The reader is thus invited to take this step of renewed commitment to YHWH's word, as the psalm itself provides an appropriate training ground for them to do so (see the feature, Asyndeton).

The number 8 is also salient in the placement of those verses containing two Torah words throughout the psalm. v. 16 is two eights from the beginning, followed by v. 48, four eights from v. 16. The final three instances are 16 verses from the end, 8 verses from the end, and 4 verses (half of 8) from the end, perhaps indicating a closing in on understanding and the dissolution of frustration.

Note: If the correct number were ten (dispreferred), an analogy to the ten words of the Decalogue could be in view.

3.Always and Forever

- **v. 22: For the revocalization גֹּל, see the Grammar note (MT: גַּל).

- **v. 37: For the emendation כִּדְבָרְךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: בִּדְרָכֶ֥ךָ).

- **v. 98: For the revocalization מִצְוָתֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִצְוֺתֶ֑ךָ).

- **v. 119: For the emendation חָשַׁבְתָּ, see the Grammar note (MT: הִשְׁבַּ֥תָּ).

- **v. 128: For the emendation פִּקּוּדֶיךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: פִּקּ֣וּדֵי כֹ֣ל).

- **v. 137: For the emendation מִשְׁפָּטֶךָ, see the Grammar note (MT: מִשְׁפָּטֶֽיךָ).

Feature

The first temporal adverb in Psalm 119 is בְכָל־עֵֽת in v. 20, before עֵֽקֶב in v. 33, the cluster of וָעֶֽד לְעוֹלָ֥ם תָמִ֗יד in v. 44 and מֵעוֹלָ֥ם in v. 52. The cluster in v. 44 falls at exactly the half-way point of the first half of the psalm (vv. 1-88).

From v. 89 onwards the temporal adverbs become increasingly frequent, especially לְעוֹלָם, the first word of the second half of the psalm, the first word of the second half of the lamed stanza, and present at the beginning of the final verse (usually final line) of the nun, tsade, qoph and resh stanzas (vv. 112, 144, 152, 160). A pattern of double לְעוֹלָם is established at the beginning and end of the central section of the psalm (vv. 89, 93; vv. 111-112); and resumed in vv. 142, 144 to begin the three-fold pattern of concluding the stanza with the word, excluding the final two stanzas, which form another independent unit analogous to vv. 89-112 (see poetic structure).

Effect

The temporal adverbs used in Psalm 119 function to remind the reader that, despite the difficult circumstances the psalmist was experiencing, he could trust YHWH that his word and attributes were from eternity past (מֵעוֹלָ֥ם; v. 52) and remain true into the future (לְעוֹלָ֣ם; v. 152). Thus, the present experience is equally under YHWH's sovereign control, just as he was sovereign over the beginning of all things and will be until the end of all things.

Structurally, the most significant clusters of temporal adverbs, notably containing לְעוֹלָם, occur immediately following sustained laments (vv. 89-93, following vv. 81-88; vv. 111-112 following vv. 107-110; see speech act analysis). Although it seemed like he was always in danger (v. 109), and that this was worth lamenting, it nonetheless remains true that YHWH's "faithfulness is toward each generation" (v. 90). As a result, the psalmist desired to be close to YHWH and his word “all the time” (v. 20) and to walk in his ways forever (vv. 33, 44) The psalmist could rest in the fact that everything comes to an end, except YHWH's faithfulness to his word (v. 112). While the presence of suffering provides the temptation to become blinded by current circumstances, the psalmist returns to focus on what is always and forever true. YHWH’s instruction carries the psalmist through it all.

Bibliography

- Auffret, P. 2006. Mais Tu Élargirais mon Cœur: Nouvelle Étude Structurelle du Psaume 119. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Fokkelman, J. P. 2003. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: at the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis. Vol. III: The Remaining 65 Psalms. Assen: Royal van Gorcum, 235-270.

- Freedman, D. N. 1999. Psalm 119: The Exaltation of Torah. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Girard, M. 1994. Les Psaumes Redécouverts: de la Structure au Sens. Québec: Bellarmin, 240-286.

- James, E. T. 2022. "The Aesthetics of Biblical Acrostics." Pages 319-338 in JSOT 46(3).

- Labuschagne, C. J. 2012. Psalm 119 – Logotechnical Analysis.

- Reynolds, K. 2010. Torah as Teacher: The Exemplary Torah Student in Psalm 119. Leiden: Brill.

- Snearly, M. K. 2015. The Return of the King: Messianic Expectations in Book V of the Psalter. New York, NY: Bloomsbury T&T Clark.

- Soll, W. 1991. Psalm 119: Matrix, Form and Setting. Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America.

- van der Lugt, P. 2013. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1. Leiden: Brill, 296-345.

- Zenger, E. 2011. "Psalm 119." Pages 247-285 in F. Hossfeld & E. Zenger, Psalms 3. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.