Psalm 8/Summary

Summary

Line divisions

- 2a יְהוָ֤ה אֲדֹנֵ֗ינוּ

- 2b מָֽה־אַדִּ֣יר שִׁ֭מְךָ בְּכָל־הָאָ֑רֶץ

- 2c אֲשֶׁ֥ר תְּנָ֥ה ה֜וֹדְךָ֗ עַל־הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃

- 3a מִפִּ֤י עֽוֹלְלִ֙ים׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֘

- 3b יִסַּ֪דְתָּ֫ עֹ֥ז לְמַ֥עַן צוֹרְרֶ֑יךָ

- 3c לְהַשְׁבִּ֥ית א֜וֹיֵ֗ב וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם׃

- 4a כִּֽי־אֶרְאֶ֣ה שָׁ֭מֶיךָ מַעֲשֵׂ֣י אֶצְבְּעֹתֶ֑יךָ

- 4b יָרֵ֥חַ וְ֜כוֹכָבִ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר כּוֹנָֽנְתָּה׃

- 5a מָֽה־אֱנ֥וֹשׁ כִּֽי־תִזְכְּרֶ֑נּוּ

- 5b וּבֶן־אָ֜דָ֗ם כִּ֣י תִפְקְדֶֽנּוּ׃

- 6a וַתְּחַסְּרֵ֣הוּ מְּ֭עַט מֵאֱלֹהִ֑ים

- 6b וְכָב֖וֹד וְהָדָ֣ר תְּעַטְּרֵֽהוּ׃

- 7a תַּ֭מְשִׁילֵהוּ בְּמַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָדֶ֑יךָ

- 7b כֹּ֜ל שַׁ֣תָּה תַֽחַת־רַגְלָֽיו׃

- 8a צֹנֶ֣ה וַאֲלָפִ֣ים כֻּלָּ֑ם

- 8b וְ֜גַ֗ם בַּהֲמ֥וֹת שָׂדָֽי׃

- 9a צִפּ֣וֹר שָׁ֭מַיִם וּדְגֵ֣י הַיָּ֑ם

- 9b עֹ֜בֵ֗ר אָרְח֥וֹת יַמִּֽים׃

- 10a יְהוָ֥ה אֲדֹנֵ֑ינוּ

- 10b מָֽה־אַדִּ֥יר שִׁ֜מְךָ֗ בְּכָל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃

- v.3. The Masoretic accents suggest a line division after יִסַּ֪דְתָּ֫ עֹ֥ז (note עולה ויורד, which is "used to mark the main verse division").[1] This division appears to be followed by the ancient versions.

- However, there is a strong argument to be made for dividing the first line of v.3 after וְֽיֹנְקִים֘ (as above) rather than after עֹז. The first line of argument is prosodic. The MT division leaves v.3a as the longest line in the psalm (14 syllables, 5 words, 5 stress units), more than twice as long as v.3b (6/2/2) and significantly longer than v.3c (9/3/3). If, however, the division is placed after ינקים, then a balanced rhythm is achieved (v.3a: 9/3/3, v.3b: 10/4/4, v.3c: 9/3/3). Note that v.3a and v.3c are identical in length (9 syllables, 3 words, 3 stress-units). This prosodic identity is reinforced by a number of other correspondences, both phonological (a פִּי b עוֹ c ינקים // a' בִּית b' אוֹ c' ומתנקם) and morphological (participles: עֽוֹלְלִ֙ים׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֘ // א֜וֹיֵ֗ב וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם). These parallels are brought into sharp focus when the line is divided as above (note especially the similar endings [epiphora]: v.3a: וְֽיֹנְקִים֘; v.3c: וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם). Similarly, there are correspondences between v.2c and v.3b. The words הוֹד (v.2c) and עז (v.3b) are connected phonologically as well as lexically. The two lines, furthermore, are similar in length (v.2c: 11/5/4; v.3b: 10/4/4), each having 4 stress-units. The number of correspondences among vv.2c-3c (v.2c-->v.3b; v.3a-->v.3c) suggest that these four lines together form a section, each half forming a bicolon. This is the way in which the rest of the psalm is structured as well (see Section divisions and Cohesion); lines are paired into bicola, which are paired into sections (quatrains). The lines of the first section (quatrain) are thus divided as follows:

| מפי עוללים וינקים | // | אשׁר תנה הודך על השׁמים |

| להשׁבית אויב ומתנקם | // | יסדת עז למען צורריך |

- "The B-cola now have a word pair each; although one is in the plural and the other in the singular, together they are four collectives. Syntactically, these half-verses are no more than complements. The core clauses to which they form explanations are in the A-cola, with perfect forms in front positions [Fokkelman reads תנה as תֻּנָּה, pual perfect of תנה]. Immediately following there the subject/object, with the monosyllables הוֹד and עֹז, which correspond in sound and meaning and both honour the deity, and finally a prepositional word group."[2]

- A significant number of modern translations have adopted this same division (AT, NEB, JB, RSV, TEV).[3] This division between v.3a and v.3b is also presented in the Leningrad Codex (by a space in the manuscript).,

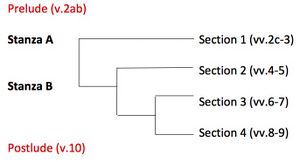

Section divisions

- Prelude (v.2ab)

- Section 1 (vv.2c-3c)

- Section 2 (vv.4-5)

- Section 3 (vv.6-7)

- Section 4 (vv.8-9)

- Postlude (v.10)

OR

- First two lines (Inclusio, 2ab)

- Stanza A (2c-3)

- Stanza B (4-9)

- Last two lines (Inclusio, 10)

These two proposals are not necessarily contradictory. One may maintain a four-part structure (1st proposal) while asserting that the strongest division in the psalm is between vv.3-4 (2nd proposal). These structures have been harmonized in the diagram to the right.

Keil and Delitzsch object to grouping v.2c with the first strophe in the body of the poem on the grounds that "אשׁר is not rightly adapted to begin a strophe."[4] However, while "beginning a strophe with the word אשׁר is uncommon... it does happen elsewhere: Pss. 71:20, 89:22a, and 105:9a."[5] There is good reason to think that it happens here as well (see the argument above).,

Communicative function

Psalm 8 is a hymn of praise, written "in direct address to God, the only such hymn in the Old Testament composed completely in the form of such address."[6] See below on Genre.,

Range of emotions

- Prelude (v.2ab): Admiration

- Section 1 (vv.2c-3c): Admiration + Surprise

- Section 2 (vv.4-5): Admiration + Awe + Amazement

- Section 3 (vv.6-7): Admiration + Amazement

- Section 4 (vv.8-9): Admiration + Amazement

- Postlude (v.10): Admiration,

Prominence

Repetition of מָה (vv.2b,5a,10b) marks vv.5-6 as "the central point of the psalm. The balanced poetic lines in v.5 and v.6 stand out in the middle of the psalm. Verse 6 is connected to v.5 by the unusual appearance in poetry of the waw-conjunction with an imperfect verb form at the beginning of v.6, which emphasizes the verse. Further, the chiastic structure of v.6 tends to make it as the focal point of the psalm... In addition, there is a rhyming of the last syllables of the verbs in vv.5-6, רֶנּוּ and דֶנּוּ followed by רֵהוּ and רֵהוּ that increases the force of the statements. Also, Øystein Lund argues that v.5 is based on the statements in vv.3-4, and that vv.6-7 form a continuation of the wonder expressed in v.5."[7]

"In Psalm 8, as in many chiastic arrangements, the key verses appear in the middle of the psalm precisely because the remainder of the psalm is a carefully structured shell that frames the vital elements in the center."[8],

Main message

Yahweh's majesty is manifested (surprisingly) in weak humanity.,

Large-scale structures

Inclusion (vv.2ab, 10ab).

"A perfect circle is closed: the majesty of God, affirmed at the beginning, restated verbatim at the end, but with the sense accrued through the intervening eight lines of what concretely it means for His name to be majestic throughout the earth"[9] The "sense accrued" throughout the psalm is surprising. The opening declaration of Yahweh's majesty (v.2ab) is expounded, perhaps unexpectedly, with images of helpless children (v.3) and frail humans (v.5). When the same words are repeated in v.10, the meaning has developed in a surprising way: Yahweh's royal majesty is manifested in weakness.

Concentric Pattern I (ABCC'B'A')

"Verses 2ab and 10 form an unmistakable inclusion: the envelope containing what I will now call the body of the poem. This body is highly regular, as it consists of four S-strophes with a quartet of cola each. Two strophes full of collectives (vv.2c-3c and 8-9) circle round the core that presents a type of soliloquy, structured as question (vv.4-5 = strophe 3) and answer (strophe 4, vv.6-7). Thus, at strophe level there is a concentric ABC-C'B'A' pattern."[10]

Terrien proposes the same concentric structure:[11]

- Prelude: The Marvel of the Name (v.2ab)

- Strophe I: The Majesty of God (vv.2c-3)

- Strophe II: The Fragility of Man (vv.4-5)

- Strophe III: The Greatness of Man (vv.6-7)

- Strophe IV: The Service of the Animals (vv.8-9)

- Strophe I: The Majesty of God (vv.2c-3)

- Postlude: The Marvel of the Name (v.10)

"The prelude and postlude, in mirror identity, form with the four quatrains two kinds of chiasmus, which situate humankind in their fragility and greatness between the majesty of God and the abundance of animal food for the survival of human beings."[12]

Concentric Pattern II (ABCDEE'D'C'B'A')

Kraut breaks down this concentric structure in even greater detail:

- A. יְהוָ֤ה אֲדֹנֵ֗ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֣יר שִׁ֭מְךָ בְּכָל־הָאָ֑רֶץ

- B. אֲשֶׁ֥ר תְּנָ֥ה ה֜וֹדְךָ֗ עַל־הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃ מִפִּ֤י עֽוֹלְלִ֙ים׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֘

- C. יִסַּ֪דְתָּ֫ עֹ֥ז לְמַ֥עַן צוֹרְרֶ֑יךָ לְהַשְׁבִּ֥ית א֜וֹיֵ֗ב וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם׃

- D. כִּֽי־אֶרְאֶ֣ה שָׁ֭מֶיךָ מַעֲשֵׂ֣י אֶצְבְּעֹתֶ֑יךָ יָרֵ֥חַ וְ֜כוֹכָבִ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר כּוֹנָֽנְתָּה׃

- E. מָֽה־אֱנ֥וֹשׁ כִּֽי־תִזְכְּרֶ֑נּוּ וּבֶן־אָ֜דָ֗ם כִּ֣י תִפְקְדֶֽנּוּ׃

- E'. וַתְּחַסְּרֵ֣הוּ מְּ֭עַט מֵאֱלֹהִ֑ים וְכָב֖וֹד וְהָדָ֣ר תְּעַטְּרֵֽהוּ׃

- D'. תַּ֭מְשִׁילֵהוּ בְּמַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָדֶ֑יךָ כֹּ֜ל שַׁ֣תָּה תַֽחַת־רַגְלָֽיו׃

- D. כִּֽי־אֶרְאֶ֣ה שָׁ֭מֶיךָ מַעֲשֵׂ֣י אֶצְבְּעֹתֶ֑יךָ יָרֵ֥חַ וְ֜כוֹכָבִ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר כּוֹנָֽנְתָּה׃

- C'. צֹנֶ֣ה וַאֲלָפִ֣ים כֻּלָּ֑ם וְ֜גַ֗ם בַּהֲמ֥וֹת שָׂדָֽי׃

- C. יִסַּ֪דְתָּ֫ עֹ֥ז לְמַ֥עַן צוֹרְרֶ֑יךָ לְהַשְׁבִּ֥ית א֜וֹיֵ֗ב וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם׃

- B'. צִפּ֣וֹר שָׁ֭מַיִם וּדְגֵ֣י הַיָּ֑ם עֹ֜בֵ֗ר אָרְח֥וֹת יַמִּֽים׃

- B. אֲשֶׁ֥ר תְּנָ֥ה ה֜וֹדְךָ֗ עַל־הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃ מִפִּ֤י עֽוֹלְלִ֙ים׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֘

- A'. יְהוָ֥ה אֲדֹנֵ֑ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֥יר שִׁ֜מְךָ֗ בְּכָל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃

"The symmetry coursing through Psalm 8 is actually an elaborately conceived chiastic structure with five elements in each half of the chiasm (see above). The chiasm can be identified on the basis of two sorts of indications in corresponding chiastic elements, which I will call 'parallel language' and 'conceptual parallels.'"[13] The parallel language is emboldened above. Some of the conceptual parallels are summarized below:

- B/B' – "Elements B and B' share a common theme. Each expresses the extent of a dominion: God’s or man’s, respectively."[14] Furthermore, mention of prattling children corresponds to that of chirping birds, and "sucklings" corresponds to fish who make a sucking motion. "God’s mastery over the babbling and sucking humans (B) is compared with man’s mastery over the babbling and sucking creatures of the animal kingdom (B’)."[15]

- C/C' – "In each element, three beings (or groups of beings) are identified. In C, God is said to have overcome three types of adversaries: צורר, אויב ומתנקם. In C’, which describes man’s dominion over the animal kingdom, three types of animals are listed: צנה ואלפים, and בהמות."[16] Note also the phonological correspondences: צנה - צורר (beginning with tsade); אויב - ואלפים (beginning with alef); גם in v.9b sounds like קם in v.3c.

- D/D' – "Yet again, invocation of God’s dominion in the first half of the psalm (D) is paralleled in the second half of the psalm by invocation of man’s God-granted dominion over the natural world (D’).[17],

Translation

Poetic Translation by Ryan Sikes

- Yahweh our master,

- Your name is majestic in all the earth!

- Your royal worth is exalted* above the skies

- At the cries of children.

- You founded a fortress because of your foes

- To stop a vengeful villain.

- When I look at the skies, your hand-work of art,

- The moon and stars installed,

- How small is man to receive your regard!

- The son of man, your call!

- Yet you made him just shy of one deified,

- With dignified honor his crown.

- You give him reign over all your hands made.

- Under his feet lay all down.

- All kinds of livestock – cattle and sheep,

- Even the beasts untamed

- The birds of the sky, the fish of the sea

- That travel the ocean’s ways.

- Yahweh our master,

- Your name is majestic in all the earth!,

Outline or visual representation

(This began as Wendland's Expository outline[18], but may be adapted.)

I. God is great and His name is majestic as evidenced by. (1-3)

- A. The Heavens.

- B. The praise of His children.

- C. His greatest creation, mankind.

II. Man is God’s greatest creation. (3-8)

- A. God thinks on him and cares for him.

- B. Man is just a little lower than the angels.

- C. Man is crowned with glory and majesty.

- D. Man rules over the work of God’s hands.

- E. All things are under his feet–animals, birds, and fish.

III. God is great: The psalm closes by repeating the opening declaration. (9)

- ↑ Israel Yeivin and E. J Revell, Introduction to the Tiberian Masorah, Masoretic Studies, No. 5. (Missoula, Mont.: Published by Scholars Press for the Society of Biblical Literature and the International Organization for Masoretic Studies, 1980).

- ↑ J.P. Fokkelman, Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis, Vol. 2 (Assen: Van Gorcum, 2000), 70.

- ↑ Robert Bratcher and William Reyburn, A Handbook on Psalms, UBS Handbook Series (New York: United Bible Societies, 1991), 78.

- ↑ C.F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament (Edinburgh: T&T Clark), 1866-91.

- ↑ Fokkelman, Major Poems, 69.

- ↑ Marvin E. Tate, “An Exposition of Psalm 8,” Perspectives in Religious Studies 28, no. 4 (Wint 2001) 343–59.

- ↑ Marvin E. Tate, “An Exposition of Psalm 8,” Perspectives in Religious Studies 28, no. 4 (Wint 2001) 343–59.

- ↑ Judah Kraut, "The Birds and the Babes: The Structure and Meaning of Psalm 8," The Jewish Quarterly Review 100, no. 1 (Wint 2010): 10–24.

- ↑ Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 148.

- ↑ Fokkelman, Major Poems, 69.

- ↑ Samuel Terrien, The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 126.

- ↑ Samuel Terrien, The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 126.

- ↑ Judah Kraut, "The Birds and the Babes: The Structure and Meaning of Psalm 8," The Jewish Quarterly Review 100, no. 1 (Wint 2010): 10–24.

- ↑ Kraut, 20.

- ↑ Kraut, 21.

- ↑ Kraut, 21-22.

- ↑ Kraut, 22.

- ↑ Ernst Wendland, Expository Outlines of the Psalms, https://www.academia.edu/37220700/Expository_Outlines_of_the_PSALMS