Psalm 46 Poetics

About the Poetics Layer

Exploring the Psalms as poetry is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language. This layer is comprised of two main parts: poetic structure and poetic features. (For more information, click 'Expand' to the right.)

Poetic Structure

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into sub-sections, sub-sections into larger sections, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

Poetics Visuals for Psalm 46

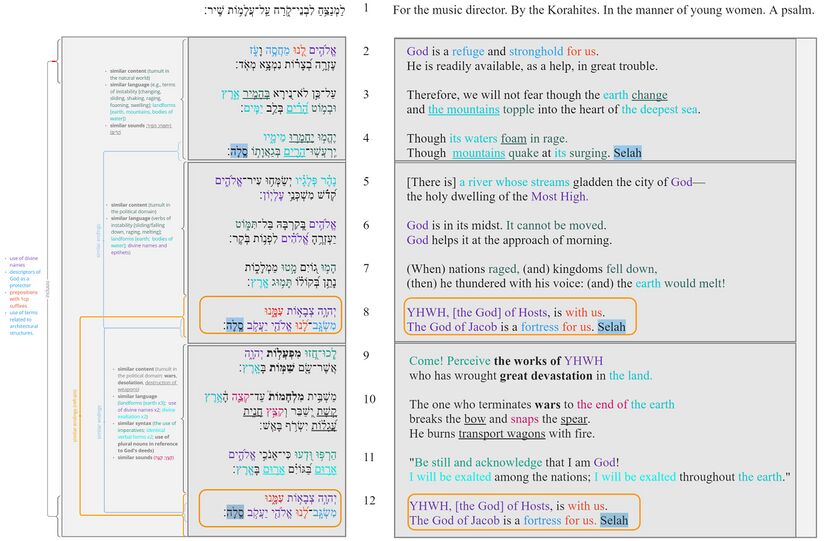

Poetic Structure

Poetic Macro-structure

The psalm can be divided into three major parts (vv. 2–4, vv. 5–7, and vv. 9–11). After strophes 2 and 3, there is a refrain (vv. 8 and 12 respectively).[1] The three strophes are roughly equal in length, and the word Selah (rendered in the LXX as διαψαλμα [i.e., "interlude"]) finishes each section.[2] Furthermore, the psalm is framed by an inclusio: its opening and concluding sections contain divine names ("God/Elohim", "YHWH, [the God] of Hosts", and "the God of Jacob"), and descriptors of God as a protector of his people ("refuge", "stronghold", "fortress"). In strophe 1, vv. 2–4 are bound together by:

- Similarity in content (tumult in the natural world)

- Similarity in language

- Terms of instability (e.g., changing, sliding, shaking, raging, foaming, swelling)

- Terms signifying landforms (e.g., "earth", "mountains", and bodies of water)

- Similarity in sound (יחמרו ;הרים ;המיר)

- Similarity in number of lines (2 lines)

- Similarity in length of lines (4 lines of 4 prosodic words each and 2 lines of 3 prosodic words)[3]

The strophe finishes with a Selah.

In strophe 2, vv. 5–7 are bound together by:

- Similarity in content (tumult in the political domain)

- Similarity in language

- Terms of instability (e.g., toppling, raging, melting)

- Terms signifying landforms (e.g., "earth" and bodies of water)

- Terms signifying divine names and epithets

- Similarity in number of lines (2 lines)

- Similarity in length of lines (4 lines of 4 prosodic words each and 2 lines of 3 prosodic words).[4]

Similar connections exist between the strophe (vv. 5–7) and the refrain that follows it (v. 8). Namely:

- Similarity in content (divine protection; warfare)

- Similarity in language

- The use of divine names and epithets

- References to architectural structures

- Similarity in number of lines (2 lines)

- Similarity in length of lines (lines of 3 and 4 prosodic words).

Notably, the refrain (v. 8) finishes with a Selah.

In strophe 3, vv. 9–11 are linked by:

- Similarity in content

- Tumult in the political domain (wars, desolation, and destruction of weapons)

- Similarity in language

- Terms signifying landforms ("earth" x3)

- The use of divine names (x2)

- Statements about divine exaltation (x2)

- Similarity in syntax

- The use of imperatives

- Identical verbal forms (x2)

- The use of plural nouns in reference to God's deeds

- Similarity in sound (קצה; קצץ)

- Similarity in number of lines (2 sets of 2 lines and 1 set of 3 lines)

- Similarity in length of lines (4 lines of 4 prosodic words each and 3 lines of 3 prosodic words).[5]

Similar connections can also be identified between the strophe (vv. 9–11) and the refrain that follows it (v. 12):

- Similarity in content (divine protection; warfare)

- Similarity in language

- The use of divine names and epithets

- References to architectural structures

- Similarity in number of lines (2 lines)

- Similarity in length of lines (lines of 3 and 4 prosodic words).

As before, the refrain (v. 12) finishes with a Selah.

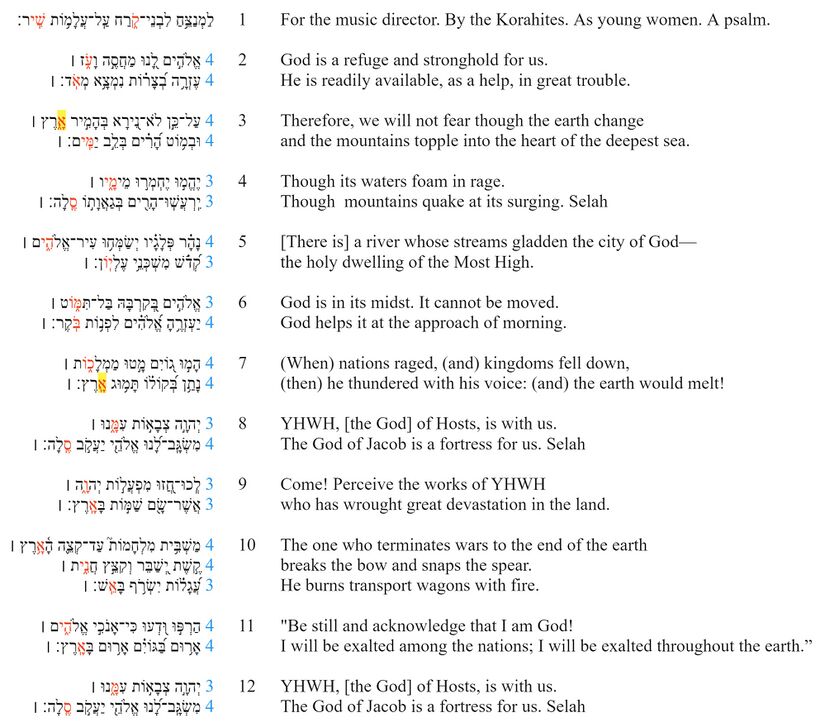

Line Division

Notes

- There are three strophes in Psalm 46 (vv. 2–4, 5–7 and 9–11), plus a refrain ("YHWH [the God of] Hosts is with us; the God of Jacob is a fortress for us") following the second and third strophes (vv. 8 and 12 respectively). Since the 19th century, scholars have suggested inserting the refrain after the first strophe as well (vv. 2–4; note the presence of a Selah after v. 4).[6] But the arguments in favor of inserting the refrain are purely internal (i.e., the presence of Selah after each strophe). There is no external textual support for such insertion. No manuscripts or versions support the inclusion of the refrain after v. 4. On the other hand, scholars observe that the omitted refrain could be a rhetorical tool to draw the reader's attention (past vv. 2-4) to the second strophe and its discussion of the city of God. Furthermore, van der Lugt argues that adding the refrain would disrupt the global level of symmetry in Psalm 46.[7] He notes that “the rhetorical structure of Psalm 46 is for positioning of verbal repetitions at exactly corresponding spots in the text." [8] So, recent structural analyses of Psalm 46 argue in support of the MT, i.e., against the addition of the refrain after v. 4.

- In v. 10, the MT has מַשְׁבִּ֥ית מִלְחָמוֹת֮ עַד־קְצֵ֪ה הָ֫אָ֥רֶץ קֶ֣שֶׁת יְ֭שַׁבֵּר וְקִצֵּ֣ץ חֲנִ֑ית עֲ֝גָל֗וֹת יִשְׂרֹ֥ף בָּאֵֽשׁ. Some scholars take the participle מַשְׁבִּ֥ית as introducing an asyndetic relative clause, i.e., “[the] one who causes wars to cease" or "stopping/terminating wars" unto the end of the earth. Others understand it as introducing a new, independent sentence ("He makes wars cease, etc.").[9] Although both options are viable, the participle מַשְׁבִּ֥ית should be taken as a substantive, i.e., “[the] one who terminates wars to the end of the earth". As such, it serves as the subject of the two yiqtols in v. 10bc. V. 9 starts with 2 imperatives ("Come! See [the works of the Lord]!"), and what is to be seen is communicated in v. 10. "The one who terminates wars" (10a) indicates a general description of God's acts. This is then followed by v. 10b, which focuses on the specific acts of destruction (i.e., breaking and burning implements of war). Furthermore, vv. 8-12 are marked by a series of concentric features, and within this section v. 10 is "pivotal."[10] "The double imperatives (lkw h.zw and hrpw wd‘w respectively), exactly at the beginning of the outer verselines (vv. 9 and 11), and b’rs (‘on earth’) exactly at the end of these lines deserve special mentioning."[11] Again, within these frames, v. 10 (describing general and specific acts of God) could be emphatic. Note, also that van der Lugt sees v. 10 as "standing out in the strophe [and also in the entire poem] because it is a tricolon." Note also that some suggest deleting v. 10c (i.e., the clause dealing with the burning of wagons) altogether. Thus, "An additional line has been added by a later editor to emphasise this destruction, but at the expense of the measure and symmetry of Str., Wagons He burneth in the fire".[12]

Poetic Features

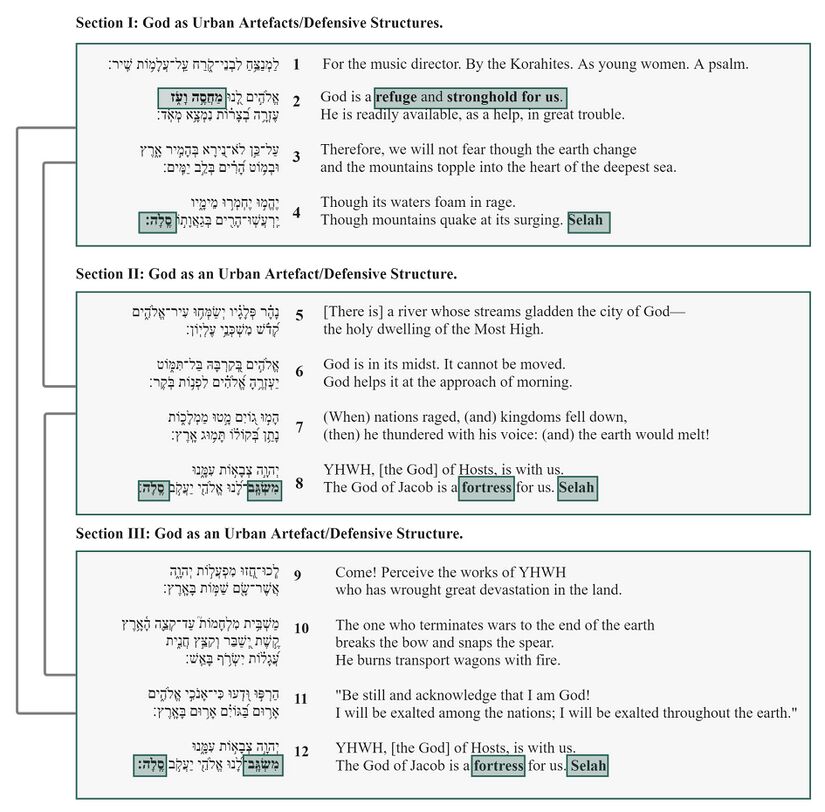

1. Poetic feature 1: God As Urban Architecture/Defensive Structures

Feature

The first section (vv. 2–4) in Psalm 46 utilizes terminology related to space and architecture to describe God in relation to his city and its people. Thus, he is imaged as a refuge (מחסה) and as a stronghold (עז). Based on Amos 3:11 and Prov 21:22, SDBH defines עז as “a construction that is strong and able to resist attacks--stronghold” (cf. Ps 61:3 [מחסה לי מגדל־עז מפני אויב׃]; Ps 91:2 [מחסי ומצודתי אלהי]; Jer 16:19 [יהוה עזי ומעזי ומנוסי]; Joel 3:16 [ויהוה מחסה לעמו ומעוז לבני ישראל]). The second and third sections (vv. 5–7 and vv. 9–11) are followed by a refrain (vv. 8, 12), wherein God is said to be a fortress (משגב), “a high and unattainable location, either because of its natural environment or as a result of human construction efforts" (SDBH). Furthermore, all three sections (vv. 4, 8, 12) finish with a סלה, a musical term, which echoes the Hebrew word “rock” (סלע). Notably, as an epithet for God, סלע appears in the Psalms alongside terms such as “refuge”, “fortress”, and “stronghold” (e.g., Ps 18:3: יהוה ׀ סלעי ומצודתי ומפלטי אלי צורי אחסה־בו מגני וקרן־ישעי משגבי; cf. Ps 31:4). Visually, it can be represented as follows:

Effect

Urbicide, “the strategic immolation of cities”, is a well-attested phenomenon in ancient warfare. In urbicide, kings at war target their opponents’ cities as political and cultural centers.[13] Echoing ANE and HB urbicide texts, Psalm 46 speaks of political tumult, whereby nations and kingdoms foam in rage, but totter and fall down (v. 7; cf. vv. 3–4); the land around God's city is said to change and shake, but is subdued and turned into desolation (vv. 3, 9). Amidst such turmoil, however, the city of God stands; it is said to never move/totter/fall down (v. 7). If in cases of successful urbicide, cities are razed to the ground, turned into heaps of ruins, and become eternal tells[14] of desolation (e.g., Josh 8:28), then Psalm 46's city is immovable. This is due to its protection by God, its divine patron, who is conceptualized through spatial and architectural metaphors (vv. 2, 8, 12). In this would-be urbicide text, God is said to be in the midst of the city (v. 6) and is part of the city-scape, i.e., he is a “refuge”, “stronghold”, and “fortress”. Additionally, located in close proximity to terms connoting architectural structures, the word Selah reinforces the image of God as a strong, immovable landmark. In a song about attempted urbicide, metaphorizing God as urban artifacts and defensive structures links the city’s fate with God’s own and guarantees its inviolability. Through this rhetorical move, the urbanization of God indicates the fortification of his city.

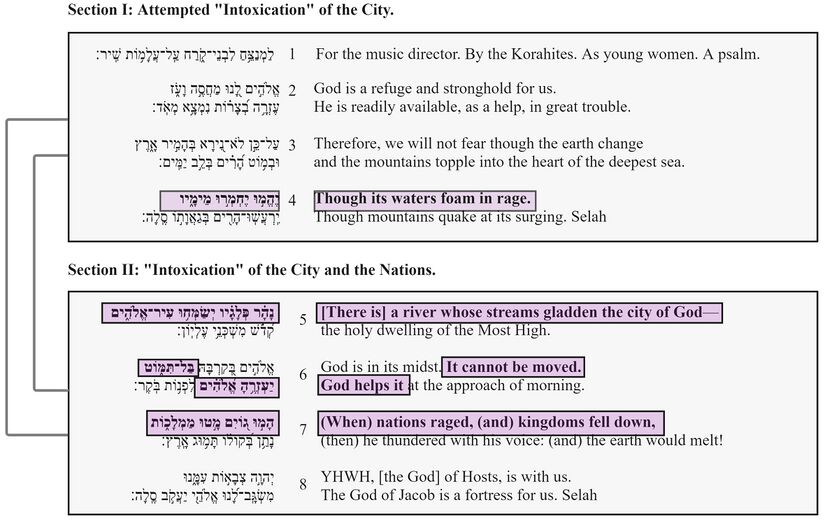

2. Poetic feature 2: Intoxication and Warfare

Feature

Alcoholic intoxication, especially with wine, was a common image used throughout the Hebrew Bible, with both negative and positive connotations. Negatively, it was common to speak of forcing a recipient to drink wine and become drunk as a metaphor for assault, judgment, and destruction, as in Jer 25:15-16 where God says “Take this cup of the wine of wrath from my hand and cause all the nations to whom I send you to drink it. They will stagger and go mad because of the sword that I will send among them” (see also Isa 29:9–10; Jer 49:12–13, 51:7; Hab 2:15–16; Lam 4:21; Ezek 23:31–34; Obad 1:16; Zech 12:2; Isa 51:17–23; cf. Job 21:20; Ps 60:3, 75:8). Positively, however, wine was associated with joy, abundance, and provision, as in Ps 104:15 where God provides "wine which makes man's heart glad" (ויין ׀ ישמח לבב־אנוש) (cf. Eccl 10:19). In Psalm 46, this image is used in three ways. First, the nations are depicted as seeking to intoxicate the city of God (vv. 3–4, 7), echoing the negative imagery of wine of wrath. Second, God is depicted as "making glad" the city and its residents (v. 5), echoing the positive imagery of good wine, and protecting them from the intoxication of the enemies (v. 6). Finally, God is depicted as intoxicating the nations, again echoing the negative imagery (v. 7, cf vv. 9–10). This unfolds through the psalm in the following way:

Section I: Attempted “Intoxication” of the City. In section I, the city of God is seen under attack from the hostile forces, metaphorized as chaotic waters (The Raging Waters in Psalm46:2-4). These in turn rage (המה; cf. Prov 20:1)[15] and foam (חמר; cf. Ps 75:8; Deut 32:14) like wine (vv. 3–4, cf. v. 7).[16] Given such aggression, the city is in danger of being “intoxicated”, i.e., of suffering military defeat. Granted, the rhetoric of instability in vv. 3–4 could be understood as representing the waters, earth, and mountains as being intoxicated themselves, while they are trying to intoxicate the city and its residents.[17] This, however, would be an overinterpretation of the images in vv. 3–4. The instability of hostile forces in vv. 3–4 indicates their tumult and aggression against the city, and anticipates their defeat (cf. vv. 7, 9–11). Their "intoxication" is properly articulated in vv. 7, 9–11, where "intoxication" imagery (losing balance and falling down, v. 7) gradually gives way to and is superseded by more overt imagery of military defeat (vv. 9–11, on which see Section II). This move from more figurative representation of military aggression (i.e., via intoxication imagery) to more overt/literal representation of military action (i.e., as terminating wars and destroying implements of war, vv. 9–11) parallels the move from more figurative representation of enemies (i.e., as the waters, earth, and mountains, vv. 3–4) to their more literal depiction (i.e., as the nations and kingdoms, vv. 7, 9–11) later in the psalm. In sum, in Psalm 46, the figurative rhetoric decreases as the "narrative" progresses, but the literal language increases. The overlap in terminology between the two (e.g., raging, falling in vv. 3–4 and 7) is needed to bind the two together and keep the overall story line cohesive and poignant.

Section II: “Intoxication” of the City and the Nations. In section II, despite its opponents' efforts, the city is supported by God (v. 5–6) and stands (בל־תמוט [v. 6]). Part of its survival is due to the presence of the river and its streams, which “gladden” the city as good wine.[18] Since ancient canal systems supplied water to cities and were part of their defensive structures (The River and Its Streams in Psalm 46), the presence of the river in v. 5 ensures the city's defense and survival. By contrast, the city's attackers are said to totter and fall down (מוט [v. 7]; cf. vv. 9–10), presumably in “drunken stupor” (cf. Hab 2:15–16; Ps 75:8; Zech 12:2, 3; cf. תמוט רגלם [Deut 32:35] in wine and judgment related context [Deut 32:23–33, cf. v. 14]). Visually, it can be represented as follows:

Effect

The effect of this feature is to employ the imagery of intoxication to create an ironic reversal throughout the psalm. The efforts of the nations to intoxicate the city and its residents are in vain. YHWH protects them (v. 6), gladdens them as if with good wine (v. 5), and instead intoxicates the nations (vv. 9–10) with the cup of his wrath.

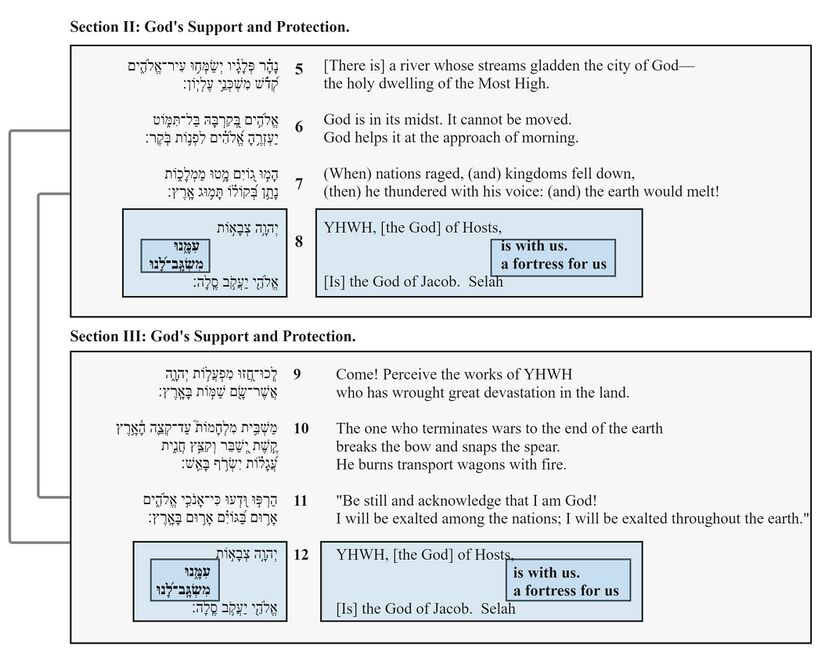

3. Poetic feature 3: Chiastic Structures: God's Support and Protection

Feature

Sections II and III (vv. 5–7 and 9–11) are followed by the refrain, YHWH, [the God] of Hosts, is with us. The God of Jacob is a fortress for us (vv. 8, 12). This refrain has a symmetric word order (a.b|b’.a’).[19] In it, in the second clause (v. 8b, v. 12b), a fortress for us (משגב־לנו) is fronted to create a chiasm with the first clause (v. 8a and v. 12a).

Effect

As previously noted, Psalm 46 can be divided into three sections, and each section highlights God’s power to sustain and protect his people in the most adverse of circumstances, i.e., warfare. Given the multitude of the enemy forces (nations and kingdoms, v. 7) and the magnitude of their military might (cf. vv. 3–4), God’s ability to protect his people is their only chance for survival. Accordingly, in the refrain, God’s role in relation to his people under attack is emphasized through chiastic arrangements of clause constituents in vv. 8 and 12—i.e., God is his people’s fortress. Through such chiastic arrangement, the psalm centers the benefits of God’s presence in his people’s lives. Given the context of warfare, these benefits literally equal their physical survival.

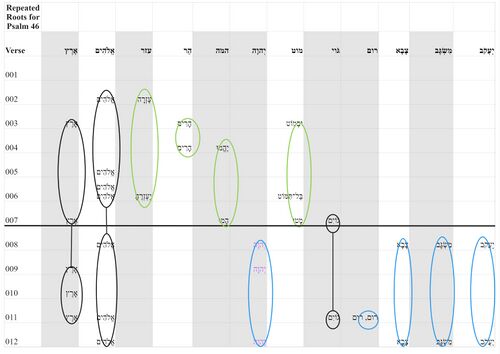

Repeated Roots

(For more information, click "Repeated Roots Legend" below.)

| Repeated Roots legend | |

|---|---|

| Divine name | The divine name is indicated by purple text. |

| Roots occurring only in the first half of the psalm are indicated in a green box. | |

| Roots occurring only on the second half of the psalm are indicated in a blue box. | |

| Roots occurring in both halves of the psalm are indicated in a black box. | |

| Roots connected across sections are indicated by a vertical black line connecting the roots. | |

| The Mid-point for the repeated roots is indicated by a horizontal black line across the chart. | |

Notes

The repetition of various roots in Psalm 46 can be said to have a structural and exegetical significance. On the one hand, through their repetition, various lexemes create a tight correlation between the strophes of the Psalm. On the other, they dictate how we interpret various entities within this composition.

- The term “earth/land”/אָרֶץ appears in all three strophes (vv. 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, and 11). Such distribution of the term holds the strophes of the psalm together. Additionally, these occurrences indicate the universal scope of God's influence and his universal exultation.

- The repetition of verbal roots in strophes 1 and 2 (vv. 2-4 and 5-7) connect the forces of nature and the nations/kingdoms of world. Just as in vv. 3–4, the waters rage (חמה) and mountains move/fall (מוט), in v. 7, the nations rage (חמה) and the kingdoms move/fall (מוט).

- Other roots link the 2 strophes together, calling for the correlation between the waters and the nations. In v. 2, God is an easily accessible help (עזרה), and in v. 6, he will help (עזר) the city under attack. So the two domains--that of nature/cosmos and history--are brought together, and one domain (nature/cosmos) stands for the other (history).

- The term אֱלֹהִים/Elohim appears seven times in the psalm (vv, 2, 5, 6 [x2], 8, 11, and 12). Mostly, representing protection, security, and stability.

- The name יְהוָה is also repeated (vv. 8, 9, and 12), but it is found at the end of Strophe 2 and in Strophe 3, both of which are militaristic in focus.

- Notably, in vv. 8 and 12, יְהוָה is paired up with the "Hosts/Armies" (appearing twice) which is a proper militaristic name for God.

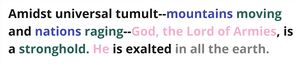

Given such distribution of terms, and commenting on the inter-relatedness between the strophes, P. Cragie notes that Psalm 46 speaks of God protecting people in different circumstances: "God’s refuge in the context of natural phenomena (vv 2–4); God’s refuge in the context of the nations of the world (vv 5–8); God’s refuge in the context of both natural and national powers (vv 9–12)."[20] Based on its repeated roots, the psalm can be summarized as follows:

Bibliography

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2018. Serial Verbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, Arnold Albert. 1981. The Book of Psalms: Based on the Revised Standard Version. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Barthélemy, Dominique. 2005. Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament. vol. 4: Psaumes. Fribourg, Switzerland: Academic Press.

- Botterweck, G. Johannes, Helmer Ringgren, and Heinz-Josef Fabry, eds. 1974–2006. Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, 15 vols. Translated by John T. Willis et al. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Briggs, Charles Augustus and Emilie Grace Briggs. 1907. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. vol. 2. ICC. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Brown, Francis, Samuel R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. 1906. A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford: Clarendon.

- The 1977 Book of Common Prayer.

- Craigie, Peter C., and Marvin E. Tate. 1983. 2nd ed. Psalms 1–50. vol. 19. WBC. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Dahood, Mitchell. 1966. Psalms. Vol. 1. Anchor Bible Commentary. New York: Doubleday.

- Day, John. 1985. God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea: Echoes of a Canaanite Myth in the Old Testament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DeClaissé-Walford, Nancy, Rolf A. Jacobson, and Beth LaNeel Tanner. 2014. The Book of Psalms. NICOT. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1883. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms. vol. 1. Translated by Eaton David. New York, NY: Funk and Wagnalls.

- Duhm, Bernhard. 1899. Die Psalmen. KHC XIV. Freiburg.

- Duhm, Bernhard. 1922. Die Psalmen. 2nd edn. KHC XIV. Tübingen.

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 2: 85 Psalms and Job 4–14). Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen, Drenthe: Van Gorcum.

- Futato, Mark D. 2007. Interpreting the Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel.

- Goldingay, John. 2007. Psalms 42–89. vol. 2. BCOT. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

- Goulder, Michael D. 1982. The Psalms of the Sons of Korah. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

- Gunkel, Hermann. 1895. Schopfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Gunkel, Hermann. 1968. Die Psalmen. HK II.2. Göttingen.

- Hayes, John. 1963. “The Tradition of Zion’s Inviolability.” Journal of Biblical Literature. 419-426.

- Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm. 1863. Commentary on the Psalms. vol. 2. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 1993. Die Psalmen I. Echter Verlag.

- Jenni, Ernst. 2012. "Nif’al und Hitpa‘el im Biblisch-Hebräischen". Pages 131-304 in Studien zur Sprachwelt des Alten Testaments III. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Jacobson, Rolf. A. 2020. "Psalm 46: Translation, Structure, and Theology." Word and World 40: 308-320.

- Junker, H. 1962. "Der Strom, dessen Arme die Stadt Gottes erfreuen (Ps. 46,5)." Biblica 43: 197-201.

- Keel, Othmar. 1997. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Tran. by T.J. Hallett. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Kelly Sidney. 1970. "Psalm 46: A Study in Imagery." Journal of Biblical Literature 89: 305-312.

- Kissane, Edward. 1953. The Book of Psalms. vol. 1, Westminster, MD: The Newman Press.

- Koehler, Ludwig, Walter Baumgartner, and Johann J. Stamm. 2001. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. 2 vols. Translated and edited under the supervision of Mervyn E. J. Richardson. Leiden: Brill.

- Kraus, Hans-Joachim. 1972. Psalmen 1–63. BKT XV/1. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag.

- Loretz, Oswald. 1979. Die Psalmen: Beitrag der Ugarit-Texte zum Verständnis von Kolometrie und Textologie der Psalmen.Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2010. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry Vol. 2. OS. Leiden: Brill.

- Lunn, Nicholas P. 2006. Word Order Variation in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: The Role of Pragmatics and Poetics in the Verbal Clause. Paternoster Biblical Monographs. Milton Keynes: Paternoster.

- The 1978 Lutheran Book of Worship.

- Mena, Andrea K. 2012. The Semantic Potential of in Genesis, Psalms, and Chronicles. MA thesis, Stellenbosch University.

- Miller, Robert D. 2010. “The Zion Hymns as Instruments of Power.” Ancient Near Eastern Studies 47: 217–39.

- Peterson, Eugene H. 2003. The Message. Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

- Raabe, P.R. 1990. Psalm Structures. A Study of Psalms with Refrains.Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 104. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

- Sawyer, John F.A. 2011. “The Terminology of the Psalm Headings.” Pages 288-298 in Sacred Text and Sacred Meanings: Studies in Biblical Language and Literature. Collected Essays by John F.A. Sawyer. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix.

- Trimm, Charlie. 2017. Fighting for the King and the Gods: A Survey of Warfare in the Ancient Near East. Resources for Biblical Studies 88. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature Press.

- Tsumura, David Toshio. 1981. "Twofold Image of Wine in Psalm 46:4-5." JQR 71: 167-175.

- Tsumura, David Toshio. 2014. Creation and Destruction: A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- VanGemeren, Willem A. 1997. New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis. 5 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Waltke, Bruce K., James M. Houston with Erika Moore, The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2010.

- Watson, Rebecca S. 2018. “'Therefore We Will Not Fear”? The Psalms of Zion in Psychological Perspective." Pages 182-216 in James K. Aitken and Hilary F. Marlow (eds.), The City in the Hebrew Bible: Critical, Literary and Exegetical Approaches. LHBOTS 672. London: T&T Clark.

- Weber, B. 2001 and 2003. Werkbuch Psalmen. 2 vols., Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Weiser, Artur. 1962. The Psalms. OTL. Trans. by Herbert Hartwell. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press.

- Welton, Rebekah. 2024. "Yahweh the Wrathful Vintner: Blood and Wine-making Metaphors in Isaiah 49:26a and 63:6." Journal for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies 4: 19-41.

- Wilson, Gerald. 2002. Psalms. volume 1. NIV Application Commentary.Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Wright, Jacob. 2015. “Urbicide: The Ritualized Killing of Cities in the Ancient Near East.” Pages 147-166 in Saul M. Olyan (ed.), Ritual Violence in the Hebrew Bible: New Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ziegler, Joseph. 1950. “Die Hilfe Gottes ‘am Morgen.’” Pages 281–88 in Alttestamentliche Studien. Edited by Hubert Junker and Johannes Botterweck. Bonn: Hanstein.

References

- ↑ Cf. Fokkelman's division (2000: 158–60): 2–4, 5–7.8| 9–11.12 [3.3.1|3.1 lines]; Weber (2001): 2–4.refrain(?)| 5–7.8|9–11.12; Gunkel (1926): 2–4+refrain, 5–8, 9–12; Duhm (1922): 2–4+refrain, 5–8, 9a+10–12.

- ↑ Cf. "Six-line stanza [Selah]; Six-line stanza, Chorus [Selah]; Six-line stanza. Chorus [Selah]" (Jacobson 2020, 314-315).

- ↑ Other notable features include: a.) repetition of the preposition ב (vv. 2b, 3a+b [2×], 4b); b.) alliteration due to the repeated הרים (vv. 3b, 4b; see also בהמיר in v. 3a); and c.) alliteration and chiasmus due to ימים and מימיו (vv. 3b and 4a) (van der Lugt 2010: 46).

- ↑ Other notable features include a.) the suffix ו (vv. 5a, 7b); b.) the preposition ב (vv. 6a, 7b); c.) the root מוט (vv. 6a,7a) (van der Lugt 2010: 46).

- ↑ Other notable features include: a.) the use of imperatives (vv. 9a and 11a) exactly at the beginning of the lines, forming an inclusio; b.) the use of יהוה/אלהים (vv. 9a and 11a; inclusio; exactly linear); c.) alliteration formed by שם שמות and משבית (vv. 9b and 10a); d.) an inclusio formed by בארץ (vv. 9b.11b) exactly at the end of the lines; e.) more uses of ב (באש [v. 10c]; and בגוים [v. 11b]); (van der Lugt 2010: 46) and f.) similarity in sound with words in vv. 3–4: ארום (x2; v. 11) and בהמיר (v. 3a) and הרים (vv. 3b, 4b).

- ↑ Cf. Craigie (1983: 342), who states, "It is possible that the twice repeated refrain (vv. 8, 12) originally occurred also after v. 5 (cf. BHS, note)." Note that H. Bardtke (BHS Psalms editor) suggests including the refrain after v. 4, according to vv. 8 and 12. Cf. Kraus (1988: 458-459), who notes that “The selah at the end of v. 3 [4] and the psalm’s structure of three uniform strophes call for the insertion of the refrain here [in v. 3] (cf. vv. 8 and 12).” See also, Gunkel (1903: 28) who says the refrain is needed for the sake of the symmetry of the strophes (cf. Briggs and Briggs 1906: 393; Anderson 1981: 355, 357; Weiser 1962: 65, 368-369; Raabe 1989: 52, 56, 59-60; see also, The Lutheran Book of Worship [1978]; The Book of Common Prayer [1977]). See, for example, the following suggestions on the structure of the Psalm: Weber [2001]: 2–4.refrain(?)| 5–7.8|9–11.12; Gunkel [1926]: 2–4+refrain, 5–8, 9–12; Duhm [1922]: 2–4+refrain, 5–8, 9a+10–12).

- ↑ van der Lugt 2010, 50.

- ↑ van der Lugt 2010, 51.

- ↑ E.g., "terminating wars to the end of the earth. He breaks the bow and snaps the spear, who burns chariots’ in fire" (Goldingay 2007: 67; cf. LSV; YLT; SLT; Douay-Rheims Bible; CPDV); "Who controls wars to the end of the world, who breaks bows and shatters lances, who burns chariots’ in fire" (Kraus 1988: 456). "He makes wars cease to the earth’s ends; he breaks the bow and shatters the spear, and burns war-wagons in the fire" (Craigie 1983: 343; most modern translation render v. 10a in a similar way); "canceling wars to the ends of the earth; he will shatter bow and break armor, and he will burn shields with fire" (LXX [NETS]; cf. Brenton Septuagint Translation).

- ↑ van der Lugt 2010: 50.

- ↑ van der Lugt 2010: 50.

- ↑ Briggs and Briggs 1906: 396, cf. 393. "This l.[ine] is trimeter and excessive to the Str. and is doubtless a gloss of intensification" (Ibid., 397).

- ↑ Wright 2015: 148.

- ↑ A tell is a mound, made up of the remains of a succession of previous settlements.

- ↑ Cf. Prov 20:1, which “implies the effect or influence of wine-drinking or wine itself, [the verb המה] probably presupposes the physical nature of wine, i.e. the raging state of foaming wine” (Tsumura 1981: 171). Cf. “to be boisterous, turbulent” as with wine (Zech 9:15).

- ↑ The verb חמר/"to foam/ferment” (v. 4) reflects the “process by which liquids form small bubbles, due to agitation or fermentation -- to foam” (SDBH; cf. “to ferment, boil, or foam up”; BDB; HALOT). Hence in Ps 46:4, the image associated with the raging, chaotic waters reflects the fermenting process in the production of wine and beer (cf. Ps 75:8; Deut 32:14) (Tsumura 1981: 167–170).

- ↑ Per discussion in The Raging Waters in Psalm46:2-4, the enemy forces in section 1 are represented by the waters alongside the earth and the mountains. For example, W. Brown argues that in this Psalm, the cosmic/natural forces such as the raging waters and quaking mountains are “mapped” onto the turbulence and instability experienced in the political realm. Hence, on a metaphoric level, the image of raging, foaming waters signifies the raging, hostile nations (Brown 2002: 116). Regarding the use of "earth" and its constituent elements (mountains, as well as waters) in Psalm 46, Kelly in turn notes that, "on the one hand, in vss. 2–6 ʾereṣ along with the mountains and waters is presented as participating in a chaotic tumult which is contrasted with the peaceful stability of the city of God; on the other hand, in vs. 11 (or vss. 9–11) ʾereṣ is presented as corresponding in nature to the city. The transition from the tumult of 'eres to her peace is accomplished in vs. 7" (Kelly 1970: 306). He further notes that, "Commentators have commonly pointed to the synonymous parallelism between vss. 3–4 and vs. 7: the shaking [...] of the mountains in vs. 3b and the roaring [...] of the waters in vs. 4a parallel the shaking [...] of the kingdoms and the roaring [...] of the nations in vs. 7a. As the actions of the nations and kingdoms may be understood as synonymous expressions for political disorder, so the actions of the mountains and waters may be understood as synonymous expressions for cosmic disorder; this is supported by their apparent parallel use in vs. 4. In turn, the activity of ʾereṣ in vs. 3a appears to parallel the tumult of the mountains in vs. 3b, and this suggests that the activity of ʾereṣ is also to be understood as paralleling the disorder of the nations/kingdoms" (Kelly 1970: 306, 307). "This conclusion is supported by the parallelism in vs. 11b where Yahweh declares his victorious exaltation with respect to [...] the nations and ʾereṣ. In turn, the parallelism of vs. 11b suggests that ʾereṣ in 7b is a cosmic image for the nations/kingdoms of 7a; thus, the political disorder is overcome and quieted in terms of the melting [...] of ʾereṣ. Indeed, vs. 11 may be considered an explication of the theophanic rebuke in vs. 7b" (Kelly 1970: 307).

- ↑ Tsumura 1981: 172.

- ↑ Raabe 1990: 59; van der Lugt 2010: 50.

- ↑ Craigie 1983: 323.