Psalm 46 Discourse

About the Discourse Layer

Our Discourse layer includes four analyses: macrosyntax, speech act analysis, emotional analysis, and participant analysis. (For more information, click 'Expand' to the right.)

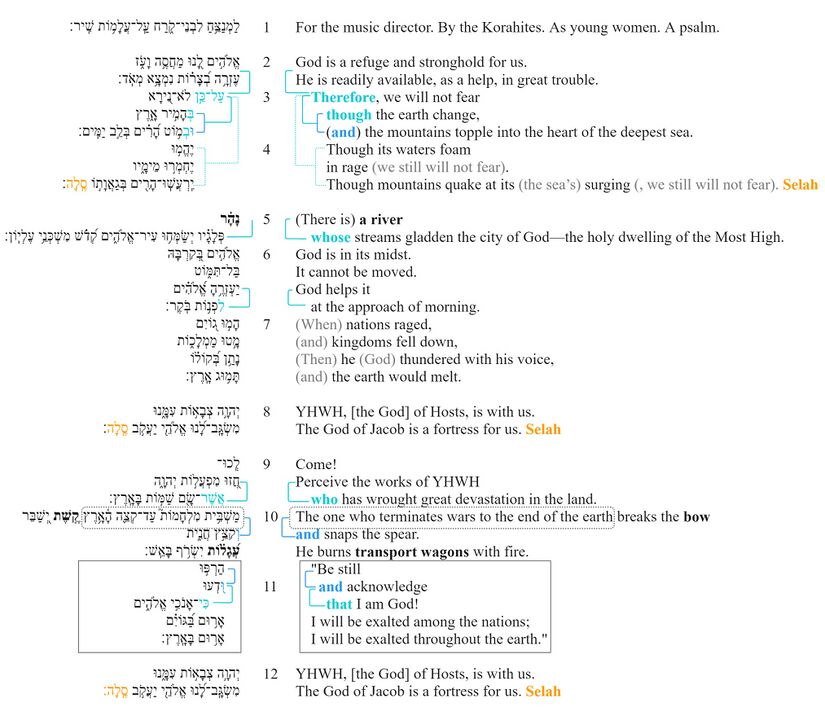

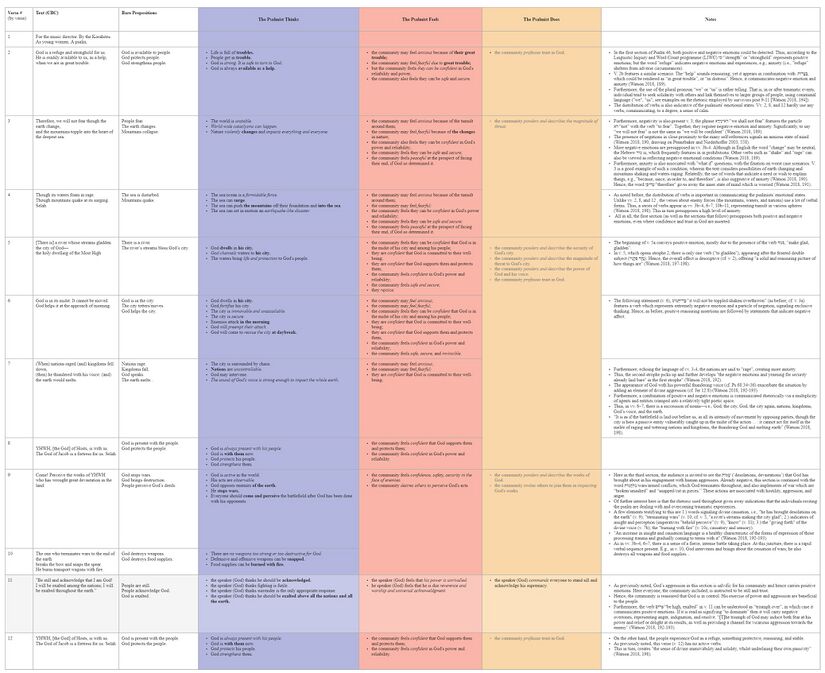

Macrosyntax

The macrosyntax layer rests on the belief that human communicators desire their addressees to receive a coherent picture of their message and will cooperatively provide clues to lead the addressee into a correct understanding. So, in the case of macrosyntax of the Psalms, the psalmist has explicitly left syntactic clues for the reader regarding the discourse structure of the entire psalm. Here we aim to account for the function of these elements, including the identification of conjunctions which either coordinate or subordinate entire clauses (as the analysis of coordinated individual phrases is carried out at the phrase-level semantics layer), vocatives, other discourse markers, direct speech, and clausal word order.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Macrosyntax Creator Guidelines.

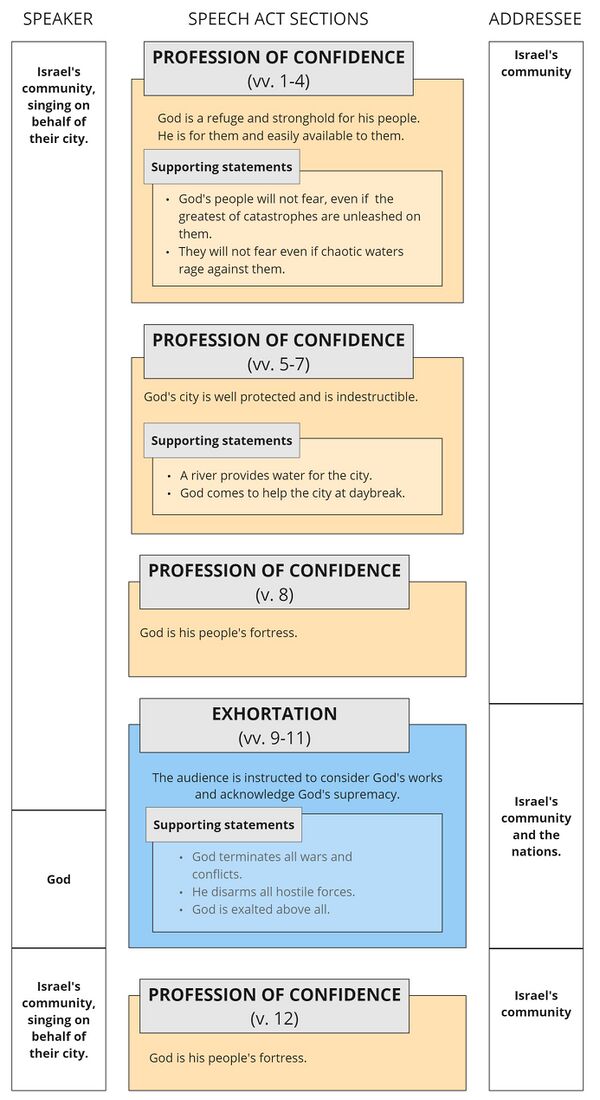

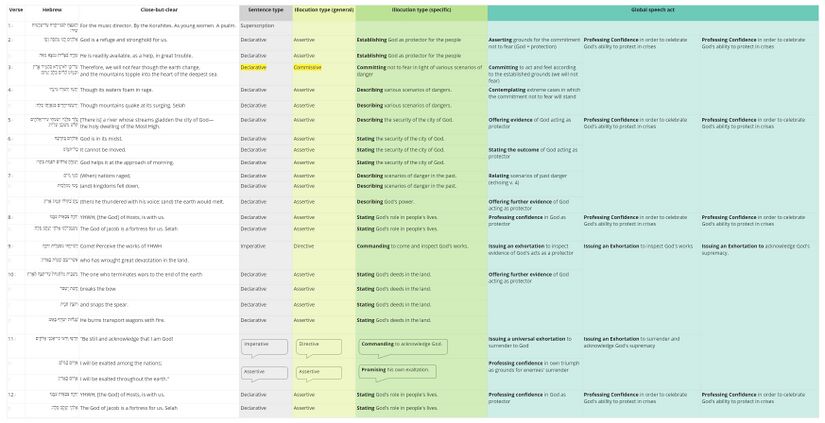

Speech Act Analysis

The Speech Act layer presents the text in terms of what it does, following the findings of Speech Act Theory. It builds on the recognition that there is more to communication than the exchange of propositions. Speech act analysis is particularly important when communicating cross-culturally, and lack of understanding can lead to serious misunderstandings, since the ways languages and cultures perform speech acts varies widely.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Speech Act Analysis Creator Guidelines.

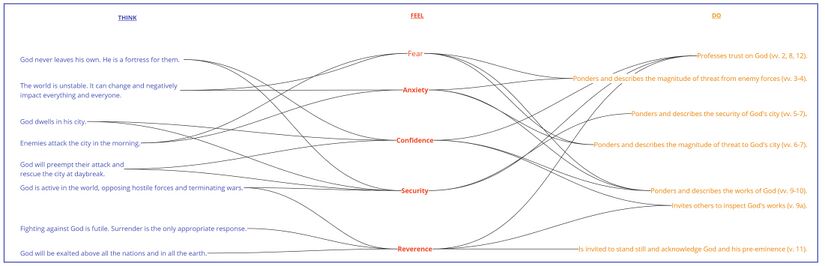

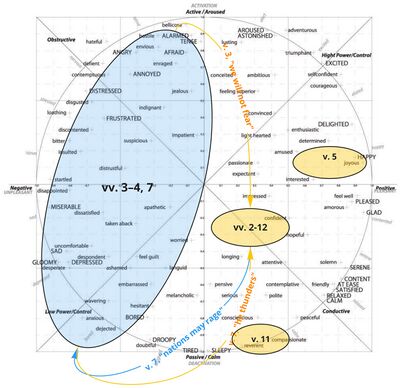

Emotional Analysis

This layer explores the emotional dimension of the biblical text and seeks to uncover the clues within the text itself that are part of the communicative intent of its author. The goal of this analysis is to chart the basic emotional tone and/or progression of the psalm.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Emotional Analysis Creator Guidelines.

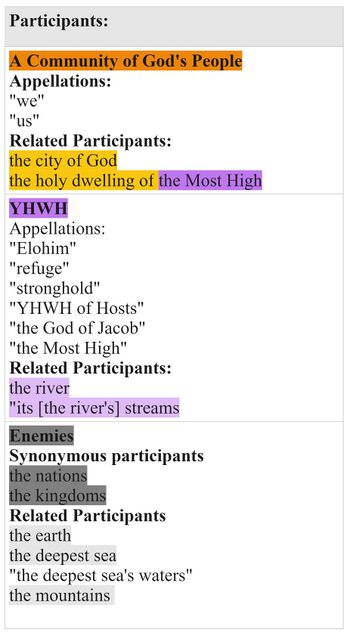

Participant Analysis

Participant Analysis focuses on the characters in the psalm and asks, “Who are the main participants (or characters) in this psalm, and what are they saying or doing? It is often helpful for understanding literary structure, speaker identification, etc.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Participant Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Discourse Visuals for Psalm 46

Macrosyntax

Notes

Paragraph Divisions

- The first section break comes after v. 4. This is indicated by a.) the presence of a Selah, a discourse marker, and b.) the opening clause of v. 5, which is a thetic statement, activating new referents ("the river and its streams").[1]

- The second section break comes after v. 7, which is indicated by the appearance of the refrain (v. 8). After it, comes a section demarcated by 2 sets of imperatives, the second of which is direct speech.

- The last section is marked by the refrain (v. 12), which in turn is marked by the final, third Selah.

Word Order

- The two clauses (v. 2a and 2b) are parallel, exhibiting an inversion of clause components, i.e., עֶזְרָ֥ה בְ֝צָר֗וֹת is fronted in v. 2b. The parallel elements are אֱלֹהִ֣ים לָ֭נוּ/"God for us"//נִמְצָ֥א מְאֹֽד/"readily available" and מַחֲסֶ֣ה וָעֹ֑ז/"a refuge and stronghold"//עֶזְרָ֥ה בְ֝צָר֗וֹת/"a help in great trouble" (> a.b|b’.a’).[2] Through such arrangement of constituents the text creates a chiastic pattern (BHRG §47.2.1[6]) whereby אֱלֹהִ֣ים לָ֭נוּ and נִמְצָ֥א מְאֹֽד stand at the beginning and end of their respective cola and frame the roles God plays in the lives of his people: מַחֲסֶ֣ה וָעֹ֑ז, עֶזְרָ֥ה בְ֝צָר֗וֹת. This inversion of syntactic constituents is poetically motivated, i.e., it centers the benefits of God's presence in his people's lives. The symmetry of v. 2 echoes the symmetry of the refrain in vv. 8 and 12 (a.b|b’.a’).[3]

- "[There is] a river" is a thetic statement, containing new information and a new referent, but the fact that it contains a body of water echoes the waters from vv. 3-4. Hence, v. 5a indicates the beginning of a new section/strophe (vv. 5–7), which focuses on God's holy city in the context of tumult in the political realm. Subject fronting in v. 5b (פְּלָגָ֗יו יְשַׂמְּח֥וּ) could be due to syntactic consideration, i.e., to assist in understanding the rest of the statement ([from Ian] see, e.g., Deut 8:9; 29:17; Ps 26:10; 144:7-8, 11; Prov 2:14-15; Eccl 10:16-17).

- The refrain (v. 8, 12) has a symmetric word order (a.b|b’.a’).[4] In it, in v. 8b (12b), מִשְׂגָּֽב־לָ֝נוּ is fronted to create a chiasmus with v. 8a (12a). This non-default word order in v. 8b (v. 12b) echoes v. 2b, i.e., its fronting of עֶזְרָ֥ה בְ֝צָר֗וֹת, and the resultant chiasmus of v. 2. In vv. 8-12, the refrain has a structuring function, i.e., it demarcates vv. 9-11 through an inclusio.[5] The word Selah appears at the end of each refrain.

- In v. 10, the text first makes a general statement about God's military activity, i.e., him terminating all wars (v. 10a, cf. v. 9), which is topical. Following this, the text zooms in on more specific acts, i.e., the destruction of implements of war (v. 10bcd), which are topically accessible (cf. vv. 9, 10a). By fronting objects in v. 10b, d, the text focalizes offensive weapons (i.e., the bow) and carts carrying supplies. This in turn indicates topic specification or expansion (BHRG §47.2.1). The reason for the unmarked word-order in וְקִצֵּ֣ץ חֲנִ֑ית is that of defamiliarisation[6], i.e. a symmetrical pattern embedded between v. 10b and 10d. "The particular ordering of the B-line in this case, we suggest, is not due to matters of pragmatics, but rather is simply a variation from the order of A, which in this context is allowable in that the marked order of A is restored in C, following the temporary departure from it in B. So taking all things into consideration, it is more accurate in such contexts as these to label the medial clause as DEF rather than CAN, since its form is a manifestation of poetic defamiliarisation (i.e. departure from the norm) rather than a question of pragmatic non-markedness. Psalm 46:10 we therefore interpret as MKD//DEF//MKD."[7]

Discourse Markers

- In v. 3, there is an עַל־כֵּ֣ן, which is an adverb, which serves as a discourse marker. Based on its components (i.e., "over" or "because of" + "these x"), this lexeme "has the deictic value of 'because of these'" (BHRG §40:38). In HB, it usually governs either qatal/perfect or yiqtol/imperfect clauses, which follow a cluster of other statements. In them, "reference is made to the grounds of the factual outcome (or result) that עַל־כֵּ֣ן introduces" (BHRG §40:38). So, in Ps 46:3, based on the assertions of v. 2 which indicate God's protection of and availability to his people, עַל־כֵּ֣ן points to "the factual outcome", i.e., the community "will not fear". The two subordinate, and coordinated statements (i.e., 'when the earth changes, (and) when the mountains topple into the heart of the deepest sea') indicate scenarios in which God's people will not fear. Macrosyntactically, there is nothing to suggest a discontinuity between vv. 2 and 3 (e.g., Selahs appear later in the psalm [vv. 4, 8, 12]; topic shifting happens after v. 4; the speaker [God's people] remains the same and direct speech appears at a later point [v. 11], etc.). In fact, together, vv. 2–4 could serve as a unit, not unlike the refrain in vv. 8, 12.

- Additionally, there are three Selahs in the psalm, appearing after vv. 4, 8, and 12.

Speech Act Analysis

Summary Visual

Speech Act Chart

Emotional Analysis

Summary visual

Emotional Analysis Chart

Emotion Distribution

Notes

Psalm 46 presupposes a set of positive and negative emotions and dispositions. Even when the text makes bold statements suggestive of confidence, security, and reverence (vv. 2, 5, 6, 8-12), negative feelings of fear and anxiety can still be detected under its surface. Yet, given the overall genre of the psalm and the recurring profession of trust (vv. 2, 8, and 12), positive emotions can be viewed as more prominent.

Participant analysis

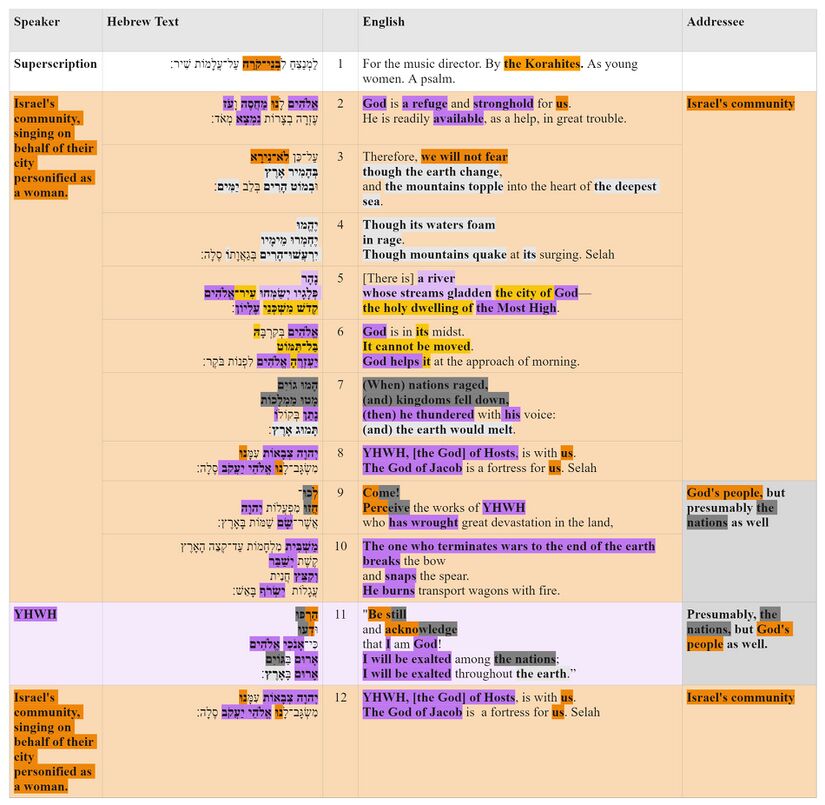

There are three main participants/characters in Psalm 46:

- A Community of God's People: is the main speaker in the psalm. The text also identifies them through self-referential appellations, i.e., “we” and "us". As per the superscription, this community was supposed to perform the psalm about God's military triumphs in the manner of a choir of young women. As such, the group was to embody their city personified as a woman (see further Participant Tracking notes). Accordingly, the community has a set of related participants (“the city of God”, “the holy dwelling of the Most High”, and “it”) who are featured as recipients of God’s care and protection amidst an international conflict.

- The City of God: The psalm offers no specific details about the identity of the city and its geographical location. The mention of mountains, sea, a river with streams providing water for a city indicates a northern site, e.g., Dan. However, "the preservation and ongoing use of the psalm so that it came to be in the Psalter imply that it came to be a Jerusalem psalm (a “Zion song”; see on Ps. 48) even though Jerusalem is unmentioned"[8]; see further The River and Its Streams in Psalm 46).

- YHWH: one of the main participants in the psalm is God, who appears under various names and appellations, i.e., Elohim, the Most High, YHWH, YHWH of Hosts, and the God of Jacob. Other descriptors featured in the song for God are “refuge”, “fortress,” and "stronghold". These architectural designations for God make his identification with the city and its community particularly intimate. In a song about attempted urbicide, the metaphorization of God as urban artifacts and landmarks links the city's fate with God's own and guarantees its inviolability.

- Nations and Kingdoms: The identity of these synonymous participants is not specified. "In the Prophets, plural 'nations' often refers to the great imperial superpower (e.g., Isa. 5:26; 14:26; 30:28), and this reference would make sense here. Ephraimite and Judean royal cities such as Dan, Samaria, and Jerusalem were vulnerable to attack by powers such as Assyria. The psalm’s declaration is that when that happens, these nations themselves fall down in the way that mountains might (v. 2), but, because of God’s presence, God’s city does not (v. 5). The nations are also characterized as kingdoms, another plural that can be used to refer to the superpower (Isa. 13:4; 47:5; Jer. 1:10, 15)."[9]

- The Natural Forces: In this set of inter-related participants, the earth, the raging waters, and the shaking mountains are given agency and literarily correlated with God’s human enemies (nations and kingdoms). Such correlation of the two groups of participants should be understood as a historicization of the ancient Near Eastern "divine conflict" motif.[10] With various degrees of personification and agentivization, these entities all engage in hostility against God and his city and people.

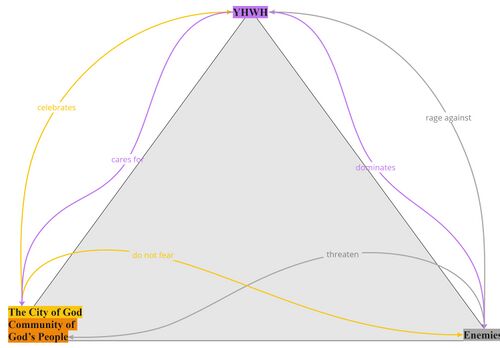

Participant Relations Diagram

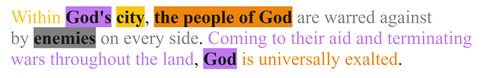

The relationships among the participants may be abstracted and summarized as follows:

Participant Analysis Table

Notes

- vv. 1–10, 12: A Community of God's People as Participants throughout the Psalm.

- In all the three sections (vv. 2–4, 5–7 and 9–10, plus the refrains in vv. 8 and 12), the community of God's people is the 'speaker'/'narrator'; in this capacity, they “stand outside” the text and can be seen as a non–agentive participant.

- They receive proper agency in vv. 2, 3, 8, and 12, where they become both a subject participant (e.g., as the recipients of God's roles and actions [for us, to us, our] and as the grammatical subject of the verb "to fear" [v. 3]).

- Additionally, they could be included in the addressees presupposed by the imperatives "Come! Perceive; Be still! Acknowledge!" in vv. 9 and 11.

- The Community as the City of God.

- Furthermore, given the instructions in the superscription in v. 1 ([to be performed] "as/in the manner of young women"), the singing community as a participant should be understood as merging with another prominent entity, i.e., the city of God (vv. 5-6). In fact, they could be singing the hymn on behalf of or as a city personified as a woman.

- Rationale for Seeing Community as the City of God:

- The word ʿalamoth (lit. “maidens, young women”) could refer to the type of a tune or musical setting, indicating the manner of the psalm’s performance (cf. 1 Chr 15:20, where it appears with “harps”).[11]

- In terms of its genre or literary type, Psalm 46 could be added to the ANE and HB traditions which feature the practice of urbicide, i.e., the ritualized killing of cities.[12] Within this category of texts, Psalm 46 can be understood as an anti-urbicide (an inverted urbicide) poem, whereby the "killing" of God's holy city is attempted but prevented, and the groups which threatened its well-being are subjected to destruction. Given that the "urbicide" motif often appears in ANE and HB city laments, as a poetic text, Psalm 46 could further be viewed as an ideological reversal of these compositions...." (on this, see The Raging Waters in Psalm46:2-4 and The River and Its Streams in Psalm 46).

- Given that a.) ANE city laments were composed as if they were sung by patron city goddesses and were performed in the emesal dialect (a dialect associated with women, but used by cultic priests); b.) ancient cities were viewed as females (e.g., Isaiah 47, Lamentations 1; 2 Sam 20:19; ANE sources; etc.); c.) war iconography which depicted cities as women, etc.; the instruction al alamot/in the manner of "young women" could indicate that the psalm (an anti-city lament, a song about the city's inviolability) needs to be performed as a choir of young women. Singing as a choir of young women, the singing community, collectively, would stand for the city itself.

- Cf. Jdg 11:24, 1 Sam 18:7, where women sang about men's military success.

- Cf. Psalm 68, which speaks of the singers and musicians, and with them are the young women/alamot playing the timbrels (v. 25). Relatedly, the timbrels accompanied songs of victory (e.g., Exod 15:20; Pss 68:11, 25-26; 149:3),[13] and all these texts deal specifically with military victories. Note also that alamot in 1 Chr 15 appears as part of a ceremony for the relocation of the ark of the covenant (a cultic object, which among other things, was carried into battles) to Jerusalem.

- And Psalm 46 is a song about God's military victory(ies).

- Natural forces in vv. 3-4 and the Nations:

- See The Raging Waters in Psalm46:2-4.

- vv. 3-4: the natural forces (the raging waters and quaking mountains) have proper agency in vv. 3-4, where they serve as subject participants (e.g., as the grammatical subjects of the verbs "to ferment", "to foam/rage", "to slide/topple", etc.).

- Additionally, they merge with the nations and kingdoms later in the text (v. 7). Hence, on a metaphoric level, the image of raging, foaming waters signifies the raging, hostile nations.

- The Nations and Kingdoms:

- The "nations" and "kingdoms" have agency in v. 7, where they serve as subject participants (e.g., as the grammatical subjects of the verbs "to rage" and to "slide/fall down"). In v. 11, they are the addressees of God's direct speech (i.e., of the imperatives "Be still! Acknowledge that I am God").

- Although the nations fall in v. 7, the fact they reappear in v. 11, where God is exalted among them, indicates that some may have survived.

- Notably, some commentators do think that the nations could be in view in both vv. 9 and 11.

- God (YHWH, YHWH of Hosts, the God of Jacob):

- In sections 1, 2 and 3 (vv. 2–4, 5–7, and 9–11, and the refrains [vv. 8 and 12]), God functions as the grammatical subject in a variety of nominal clauses and as the grammatical subject of the various verbal forms.

- In v. 11 (which contains direct speech), he also delivers a few utterances.

- The River and its Streams:

- In v. 5, God is closely associated with the river and its streams (for this, see The River and Its Streams in Psalm 46).

- The river's role in the psalm and its close association with YHWH indicate that it is an “instrument” in YHWH’s “arsenal”; it is one of YHWH’s agents, who nourishes God's city and its populace and defends it.

- Thus, the river and streams should be taken as participants related to God.

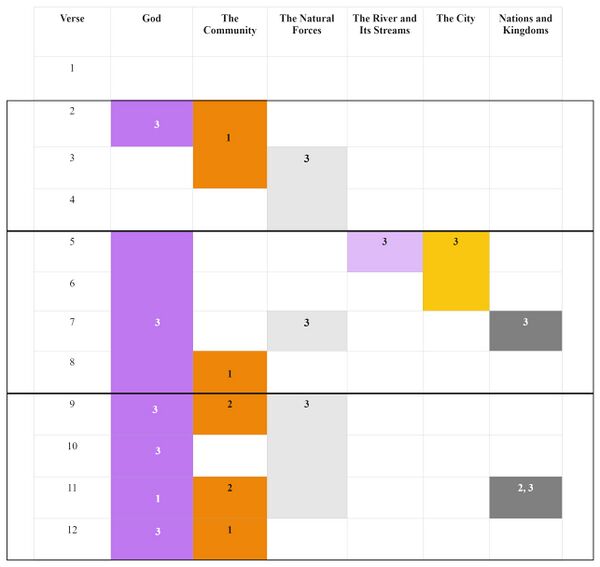

Participant Analysis Summary Distribution

Bibliography

- Craigie, Peter C., and Marvin E. Tate. 1983. 2nd ed. Psalms 1–50. vol. 19. WBC. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Day, John. 1985. God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea: Echoes of a Canaanite Myth in the Old Testament.

- Goldingay, John. 2007. Psalms 42–89. vol. 2. BCOT. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

- Keel, Othmar. 1997. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Tran. by T.J. Hallett. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2010. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry Vol. 2. OS. Leiden: Brill.

- Raabe, P.R. 1990. Psalm Structures. A Study of Psalms with Refrains.Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 104. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

- Watson, Rebecca S. 2018. “'Therefore We Will Not Fear”? The Psalms of Zion in Psychological Perspective." Pages 182-216 in James K. Aitken and Hilary F. Marlow (eds.), The City in the Hebrew Bible: Critical, Literary and Exegetical Approaches. LHBOTS 672. London: T&T Clark.

- Wright, Jacob. 2015. “Urbicide: The Ritualized Killing of Cities in the Ancient Near East.” Pages 147-166 in Saul M. Olyan (ed.), Ritual Violence in the Hebrew Bible: New Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

References

- ↑ Lunn 2004, 39-40.

- ↑ van der Lugt 2010: 46, 50.

- ↑ Raabe 1990: 59; van der Lugt 2010: 50.

- ↑ Raabe 1990: 59; van der Lugt 2010: 50.

- ↑ van der Lugt 2010: 50.

- ↑ Lunn 2004: 148-149.

- ↑ Lunn 2004: 148-49.

- ↑ Goldingay 2007: npn.

- ↑ Goldingay 2007: npn.

- ↑ Day 1985: 120.

- ↑ Craigie 2004: 324.

- ↑ Wright 2015: 147-166.

- ↑ Keel 1997: 339.