Psalm 109 Poetics

Back to Psalm 109

About the Poetics Layer

Exploring the Psalms as poetry is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language. This layer is comprised of two main parts: poetic structure and poetic features. (For more information, click 'Expand' to the right.)

Poetic Structure

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into sub-sections, sub-sections into larger sections, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

Poetics Visuals for Psalm 109

Poetic Structure

Poetic Macro-structure

Notes

- After an introductory line (v. 1), which helps frame the entire psalm (cf. vv. 30-31), the psalm divides into two main parts: vv. 2-20; vv. 21-31.[1] The first part (vv. 2-20) further divides into two smaller parts: vv. 2-5; vv. 6-20. Thus, the psalm has two or three main parts, depending on the level from which it is viewed. Many scholars agree on this basic structure—a three-section division (vv. 1/2-5; vv. 6-20; vv. 21-31), with the strongest break occurring between the second and third sections.[2] Calvin, for example, writes, "This psalm consists of three parts. It begins with a complaint; next follows an enumeration of various imprecations; and then comes a prayer with an expression of true gratitude." Van der Lugt, however, objects to this structure, claiming it is based on thematic aspects "at the cost of major structural features which are provided by its internal evidence."[3] But as the present analysis will demonstrate, this structure is based securely on both thematic and formal features of the text.

- The thematic features are clear. As Calvin writes, the first section (vv. 2-5, following the introductory v. 1) is a "complaint"; the second section (vv. 6-20) is "an enumeration of various imprecations"; and the third section is "a prayer with an expression of true gratitude."

- Formal features in the text support this three-fold division.

- Verse 20 begins with the demonstrative pronoun "this" (זֹאת), referring to vv. 6-19. Thus, the psalmist himself effectively groups these verses into a unit. This section is further distinguished by the thorough use of 3ms language, beginning in v. 6 ("appoint... against him...") and ending in v. 19 ("may it be for him..."). Verse 20 is a summary tacked on at the end.

- Verses 2-5 are characterized by 3mp language (in contrast to the 3ms language of vv. 6-19).

- The final section (vv. 21-31) begins with "but you" (וְאַתָּה)—marking a shift in discourse topic from the psalmist's accusers (vv. 2-20) to YHWH (vv. 21-31).

- Patterned repetitions in the text further support this identification of the structure.

- The first and second sections have similar beginnings: "wicked" (רָשָׁע) in v. 2a and v. 6a.

- The second and third sections (or, the two main sections of the psalm) have similar endings: v. 20b: "me" (נַפְשִׁי); v. 31b: "him" (נַפְשׁוֹ). Note also that these are the only clauses to include all three of the psalm's main participants (YHWH, the psalmist, and the accusers).

- There is a clear inclusio binding together the first two sections (vv. 1-20) and reinforcing the strong break between vv. 1-20 and vv. 21-31. Note the repetition of "accusers" (שׂטנים), "speak" (דבר), and "evil/wrong" (רע) in v. 20 and vv. 2-5.

- There is an inclusio binding together the second section (vv. 6-20): "accuse" (שׂטן).

- The grouping together of vv. 21-31 is further supported by the repetition of the vocatives that begin the two sub-sections of this unit: vv. 21-25 begin with "YHWH Lord" (יְהוִה אֲדֹנָי); and vv. 26-31 begin with "YHWH my God" (יְהוָה אֱלֹהָי).

- The two main sections of the psalm (vv. 2-20; vv. 21-31) each begin with long six-word lines—the two longest lines in the psalm.

- Thus, thematic features and formal features are not in conflict. Rather, both kinds of features work in concert to make the structure clear.[4]

Line Division

- **For the emendation קָמַי יֵבֹשׁוּ, see Grammar note (MT: קָ֤מוּ ׀ וַיֵּבֹ֗שׁוּ).

- **For the revocalizations וּתְבוֹאֵהוּ and וְתִרְחַק, see Grammar note (MT: וַתְּבוֹאֵ֑הוּ…וַתִּרְחַ֥ק).

- The above line division agree with the Masoretic accentuation[5] in every verse except possibly v. 16, though even in this verse it does not necessarily disagree. In this verse, the line division agrees with the Septuagint.

- The above line divisions agree with the Septuagint (according to Rahlfs 1931) in every verse except for v. 28 (where the Septuagint has three lines).

- All of the verses in the psalm are two-lines verses except for v. 16 and v. 18, which are three-line verses.

- Three lines are six words long (vv. 2a, 16a, 21a), and each of these long lines opens a new section in the psalm (see Poetic Structure).

Poetic Features

1. True Loyalty

- **For the emendation קָמַי יֵבֹשׁוּ, see Grammar note (MT: קָ֤מוּ ׀ וַיֵּבֹ֗שׁוּ).

- **For the revocalizations וּתְבוֹאֵהוּ and וְתִרְחַק, see Grammar note (MT: וַתְּבוֹאֵ֑הוּ…וַתִּרְחַ֥ק).

Feature

Several words and roots occurring in v. 16 (the beginning of one poetic section [vv. 16-20]) are repeated in vv. 21-22 (the beginning of the following poetic section [vv. 21-25]). These include:

- 1. עשׂה ("show," "take action")

- 2. חֶסֶד ("loyalty")

- 3. עָנִי ("afflicted")

- 4. וְאֶבְיוֹן ("and poor")

- 5. לב ("heart")

These five words occur in the same sequence in both v. 16 and vv. 21-22.

Among these repeated words/roots, the word "loyalty" (חֶסֶד) is especially prominent, occurring again at the beginning of the next section (vv. 26-31). In v. 16, the word "loyalty" (חֶסֶד) occurs with reference to the psalmist's accusers, who have failed to show loyalty (v. 16). In v. 21 and v. 26, it occurs with reference to YHWH, whose loyalty, in contrast to the accusers' loyalty, is "good" (v. 21b) and forms the basis of his plea for rescue (vv. 21, 26). The word חֶסֶד also occurs in v. 12, referring to the fact that the accuser will have no one to show him loyalty (although in this instance, the word does not occur at the beginning of a section as in vv. 16, 21, 26, and so its use here is somewhat disassociated from the pattern in vv. 16-31).

When viewed as a unit, these three final sections (vv. 16-31) also begin and end in a similar way—with the construction lamed + infinitive construct: "to finish him off" (לְמוֹתֵת, v. 16) and "to save him" (לְהוֹשִׁיעַ, v. 31). These two constructions resemble one another in that (1) they represent two of the three lamed + infinitive constructs in the psalm (cf. the other one in v. 13a); (2) they both lack direct objects (lit. "to finish off" and "to save"); (3) they both have to do with life and death respectively.

Effect

Structural. The repetition of words/roots in v. 16 and vv. 21-22 has a structural effect: the similarities mark the beginnings of new sections (vv. 16-20; vv. 21ff). The repetition of "loyalty" (חֶסֶד) in v. 26, together with other structural elements, marks the beginning of yet another section (vv. 26-31). The repetitions also give cohesion to the psalm as a whole, connecting vv. 16-20, which otherwise belong closely with vv. 2-15, to vv. 21-31. Verses 16-20 thus function as a seam, binding the two sections of the psalm, or as a janus, pointing both backwards and forwards. (See Poetic Structure for more information.)

Thematic. The repetitions also bring one of the main themes of the psalm into focus: YHWH's loyalty in contrast to human loyalty. The numerous lexical connections between v. 16 and vv. 21-22 underscore this contrast. Humans—many of them at least—are not trustworthy, and their propensity to break covenant results in death (לְמוֹתֵת, v. 16). By contrast, YHWH's loyalty is "good," i.e., "reliable" (v. 21b), leading to life and salvation (לְהוֹשִׁיעַ, v. 31). YHWH is a loyal covenant partner who can always be trusted, even when no one else can. His loyalty (vv. 21, 26) is enough to overcome the absence of loyalty that characterizes human relations (vv. 12, 16).

2. Surrounded with Words

- **For the emendation קָמַי יֵבֹשׁוּ, see Grammar note (MT: קָ֤מוּ ׀ וַיֵּבֹ֗שׁוּ).

- **For the revocalizations וּתְבוֹאֵהוּ and וְתִרְחַק, see Grammar note (MT: וַתְּבוֹאֵ֑הוּ…וַתִּרְחַ֥ק).

Feature

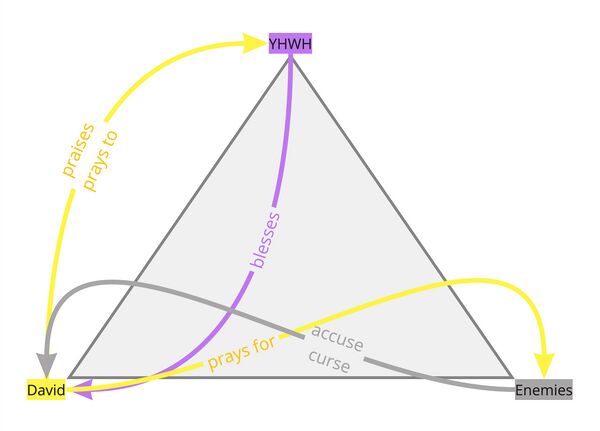

Psalm 109 begins and ends with words belonging to the semantic domain of SPEECH. The psalm begins with "praise" (v. 1), "stay silent" (v. 1), "mouth" (v. 2), "speak" (v. 2), "tongue" (v. 2), "words" (v. 3), "accuse" (v. 4), "prayer" (v. 4). Similarly, the psalm ends with "curse" (v. 28), "bless" (v. 28), "acknowledge" (v. 30), "mouth" (v. 30), and "praise" (v. 30). The repetition of the word "mouth" (vv. 2, 30) and the root "praise" (vv. 1, 30) are especially noteworthy.

Furthermore, in both the beginning and ending of the psalm, the SPEECH-related words involve all three of the psalm's main characters—the psalmist, YHWH, and the psalmist's enemies. The following visual shows how the psalm's main participants relate to one another in terms of their speech:

Effect

The repetitions highlight the theme of speech. In fact, the whole story of Psalm 109 can be told in terms of the characters' speech.

The enemies open their "mouths" (v. 2) against the psalmist, bringing baseless accusations against him (vv. 4-5) and calling down curses on him (v. 28). It is as though they make war against him, "surrounding" him with words as would an army with their weapons (v. 3).

In defense, the psalmist arms himself, as it were, with his own words, calling on YHWH to curse his enemies and rescue him (=Ps 109). In contrast to his enemies whose mouths are full of lies, his mouth is full of sincere prayer and praise (vv. 1, 4, 30).

Initially, YHWH appears to be silent (v. 1), but following the psalmist's prayer, he is sure to respond by uttering a blessing (v. 28) that will override and overpower the curse of the enemies.

3. Forgotten

- **For the emendation קָמַי יֵבֹשׁוּ, see Grammar note (MT: קָ֤מוּ ׀ וַיֵּבֹ֗שׁוּ).

- **For the revocalizations וּתְבוֹאֵהוּ and וְתִרְחַק, see Grammar note (MT: וַתְּבוֹאֵ֑הוּ…וַתִּרְחַ֥ק).

Feature

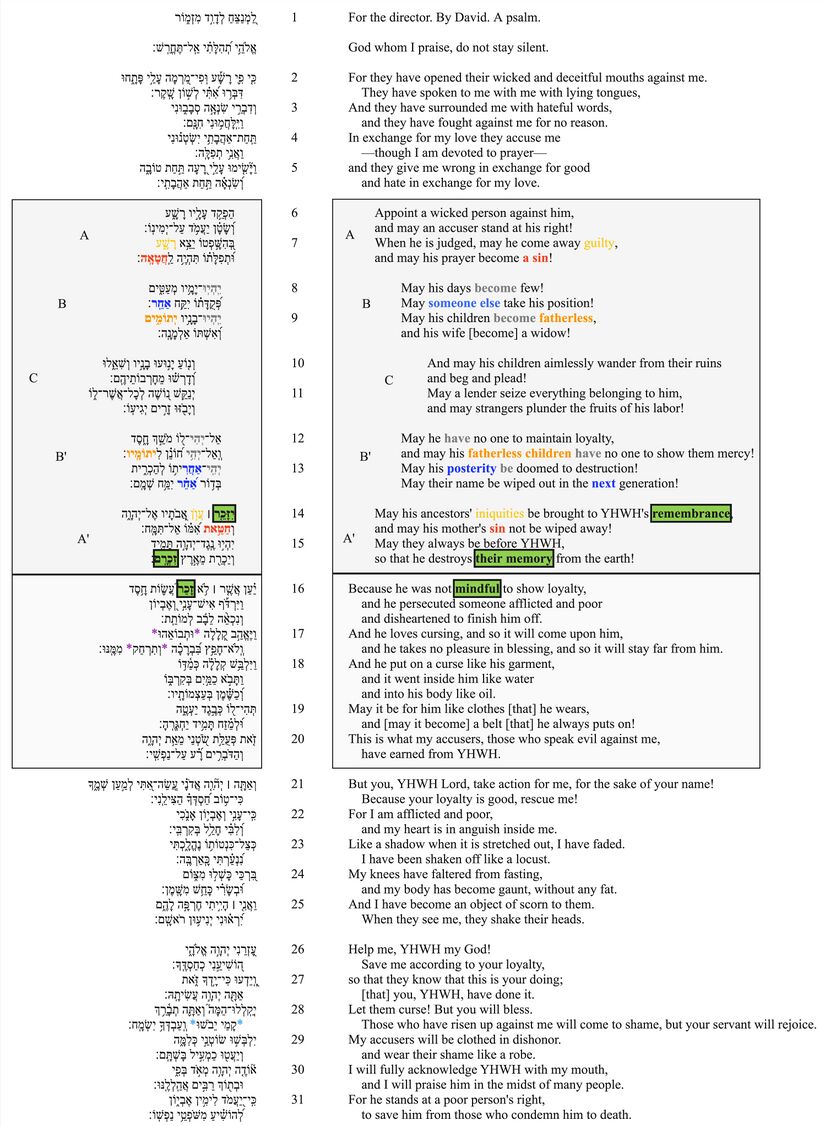

The curse section in Ps 109 (vv. 6-20)—one of the most memorable parts of this psalm—is arranged in two main parts: the curse itself (vv. 6-15) and the basis for the curse (vv. 16-20). These two parts are linked by the root זכר (vv. 14-16).

The curse itself (vv. 6-15) is arranged as a chiasm (ABCB’A’). It concerns the man’s guilt (vv. 6-7 [A]), his death (vv. 8-9 [B]), the ensuing financial devastation that results (vv. 10-11 [C]), the death of his posterity (vv. 12-13 [B’]), and even the guilt of his ancestors (vv. 14-15 [A’]). The essence of this curse is the extinction of the man’s family line, i.e., his name, or memory (זֵכֶר). Hence, the last line of the curse (v. 15b) says, in summary: “so that he destroys their memory (זִכְרָם) from the earth.

The second part of the curse section (vv. 16-20) provides the basis for this terrible curse: it is (fundamentally) "because he did not remember (זָכַר) to show loyalty." Thus, the root זכר, which occurs at the very end of the first part of the curse section, also occurs at the very beginning of the second part of the curse section. (Note that it occurs in v. 14 as well, forming a frame around vv. 14-15.)

Effect

The three-fold repetition of זכר ("remember") in such a short span of text (vv. 14-16, once in each verse) makes the idea of "remembering" especially prominent. Not only does this idea summarize the essence of curse (vv. 6-15), it also summarizes the basis for the curse (vv. 16-20). In other words, each of the accusers deserves to be completely forgotten (vv. 6-15) because each of them forgot to show loyalty (vv. 16-20). The punishment fits the crime (cf. v. 20).

Repeated Roots

The repeated roots table is intended to identify the roots which are repeated in the psalm.

For legend, click "Expand" to the right

Bibliography

- de Hoop, Raymond, and Paul Sanders. 2022. “The System of Masoretic Accentuation: Some Introductory Issues”. The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 22.

- Egwim, Stephen C. 2011. A Contextual and Cross-Cultural Study of Psalm 109. Biblical Tools and Studies, v. 12. Leuven ; Paris ; Walpole, MA: Peeters.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2013. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90–150 and Psalm 1. Vol. 3. Oudtestamentische Studiën 63. Leiden: Brill.

Footnotes

- ↑ Cf. Egwim 2011, 135, who sees two main sections (vv. 2-20; vv. 21-29) bracketed by an introduction (v. 1) and a conclusion (vv. 30-31).

- ↑ See summary of scholarship in van der Lugt 2013, 217-218.

- ↑ van der Lugt 2013, 109.

- ↑ Cf. Ps 19, which has a similar structure of two or three main sections, delimited by a combination of thematic and formal features.

- ↑ Cf. Sanders and de Hoop 2022.