Poetics proposed

DRAFT

Overseer: Ryan Sikes

Introduction

So far in our layer-by-layer analysis, we have analyzed the grammar and semantics of various psalms as well as the way in which these aspects of the language are manipulated for pragmatic effect. But we have yet to explore the Psalms as poetry. This aspect is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language.

“These poems deserve careful treatment so that the real beauty and power of the original can be felt, and the complete message can be experienced, rather than simply understood. If we reduce poetry to prose, the biblical message may lose its effect and, in a very real way, be robbed of some of its truth. Consistently translating poetic lines into flat prose is not being faithful to the text. It does not provide a dynamic, literary or functionally equivalent translation.”[1]

Steps

Our poetics layer involves the following four steps:

- Line division. Divide the poem into lines and line groupings.

- Line length. Measure the length of each line and look for patterns in line-length.

- Poetic macrostructure. Identify larger structures (strophes and stanzas) formed by combinations of lines and line groupings.

- Poetic features. Identify poetic features and their effects.

1. Line division

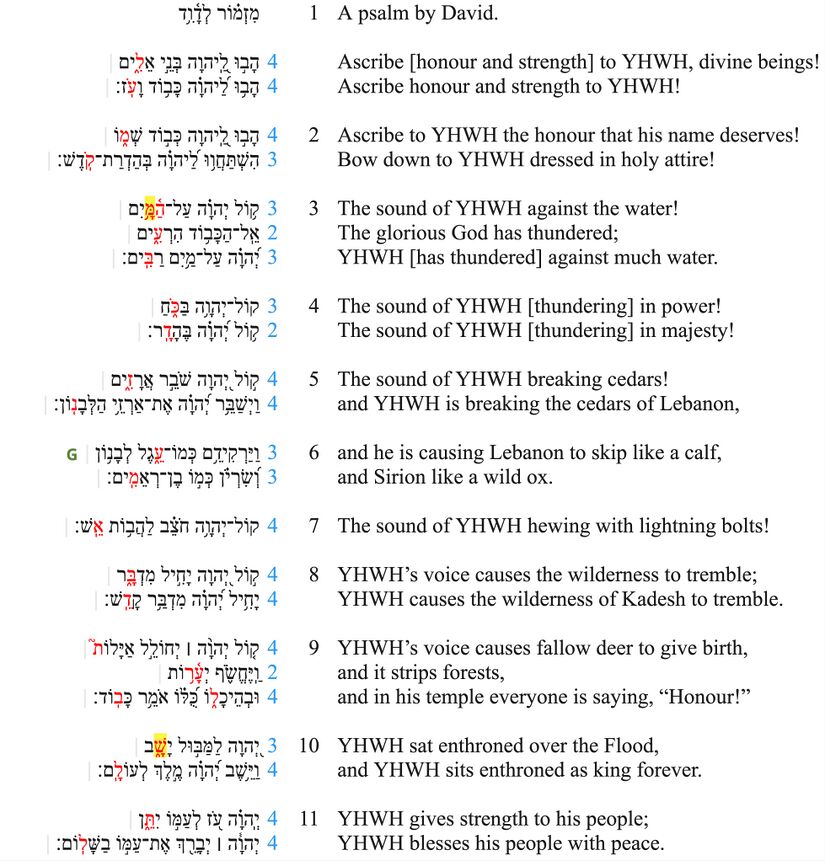

The line is the basic building block of Biblical Hebrew poetry.[2] One of the aims of this layer is to determine the line-structure of the psalm (i.e., the number of lines in the psalm as well as where each line begins and ends). Several criteria are involved in determining the line-structure.[3] These criteria are summarized in the following table:

| External Evidence | Internal Evidence |

|---|---|

| Pausal forms | Line length & balance |

| MT accents | Symmetry & parallelism |

| Manuscripts | Syntax |

- Copy the line division template from the template board.

- Copy the Hebrew text from OSHB and paste it into the relevant text box. Remove the verse numbers.

- Copy the English CBC and paste it into the relevant text box. Remove the verse numbers. (Remember that both the Hebrew and the English text should be in Times New Roman.)

- Highlight all pausal forms in the Hebrew text.[4] A complete list of pausal forms in the Hebrew bible can be downloaded here.

- Colour as red all of the accents which tend to correspond with line divisions.[5] These include the following six accents.

- silluq (e.g., יָשָֽׁב Ps. 1:1)

- 'ole weyored (e.g., חֶ֫פְצ֥וֹ Ps. 1:2 and פַּלְגֵ֫י מָ֥יִם Ps. 1:3)

- atnaḥ (e.g., הָרְשָׁעִ֑ים Ps. 1:4)[6]

- revia replacing atnaḥ (e.g., יֶהְגֶּ֗ה Ps. 1:2)[7]

- revia gadol preceded by a precursor (e.g., בְּעִתּ֗וֹ Ps. 1:3)[8]

- ṣinnor preceded by a precursor (e.g., הָלַךְ֮ Ps. 1:1).

- Insert a pipe | at each clause boundary (regardless whether the clauses are independent or subordinate). Refer to the grammatical diagram when identifying clause boundaries. Upon the completion of this step, the Hebrew text should look something like this:

- Begin spacing out the text to indicate line divisions (see image below). At this point, the divisions should be based on (1) pausal forms, (2) accents, and (3) syntax (i.e., clause boundaries). The more these terminal markers coincide at a particular point, the more likely is a line division at that point. Note that in some cases, the evidence will be conflicting or ambiguous. Further evidence is needed.

- To the right of each line of Hebrew text, list the number of prosodic words in blue. For this visual, we will define prosodic words in terms of the Masoretic tradition: any unit of text which is not divided by a space or which is joined by maqqef (or ole weyored) is a prosodic word.[9] E.g., כִּ֤י הִנֵּ֪ה הָרְשָׁעִ֡ים יִדְרְכ֬וּן קֶ֗שֶׁת contains 5 prosodic words; צַ֝דִּ֗יק מַה־פָּעָֽל contains two prosodic words; etc. The relevance of counting prosodic words is two-fold:

- The length of lines typically ranges between 2 and 5 prosodic words.[10] It may be possible for a line to contain more than 5 prosodic words, though such a line division would require justification on other grounds. If a line has more than 5 prosodic words, then bold the number (e.g. 6).

- Lines also tend to be balanced in relation to one another. Symmetrically-arranged line pairs in particular tend not to differ by more than one prosodic word.[11] Lines within a line grouping may at times be imbalanced, but this division of the text must be justified on other grounds.

- (Optional:) If some line divisions are still uncertain, it may be useful to consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. If a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences your decision to divide the text at a certain point, then place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

- Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS). Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls psalms manuscripts indicate line divisions.

- Septuagint (G). The line divisions in Rahlfs' edition are based on manuscript divisions, and they are generally reliable. Rahlfs usually notes alternate traditions of line division in the apparatus. The Codex Sinaiticus may be viewed here.

- Masoretic Manuscripts (MT). Aleppo Codex; Sassoon Codex;[12] Berlin Qu. 680 (EC1); Or2373

- In cases where the line division is ambiguous or contested, record the reasons for your preferred division in the notes section of the template.

- Indicate line-groupings by using additional spacing. Line groupings should be based on the Masoretic versification system (one verse = one line grouping) unless there is good reason to do otherwise. Superscriptions should not be included in a line grouping.

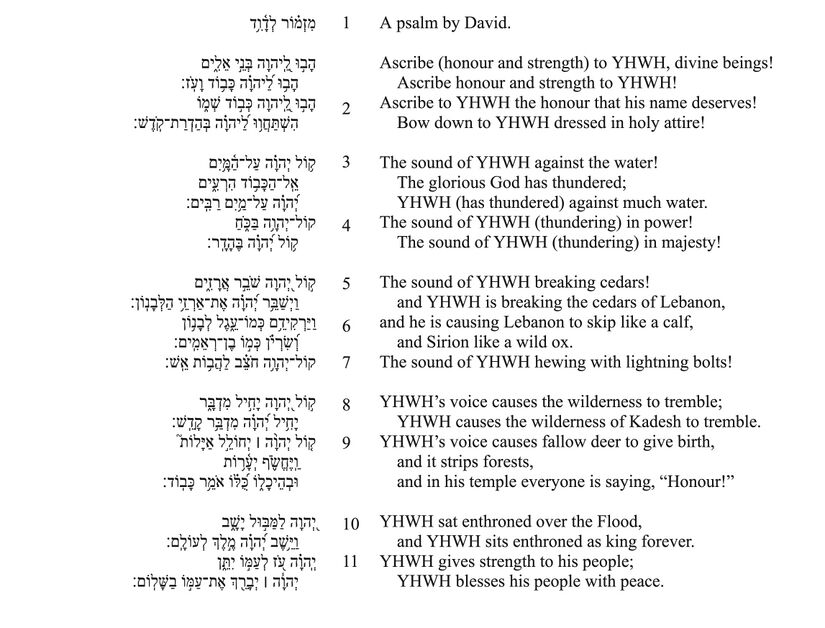

The final version should look something like the following:

- Ensure that CBC on the forum reflects the new line division.

2. Line Length

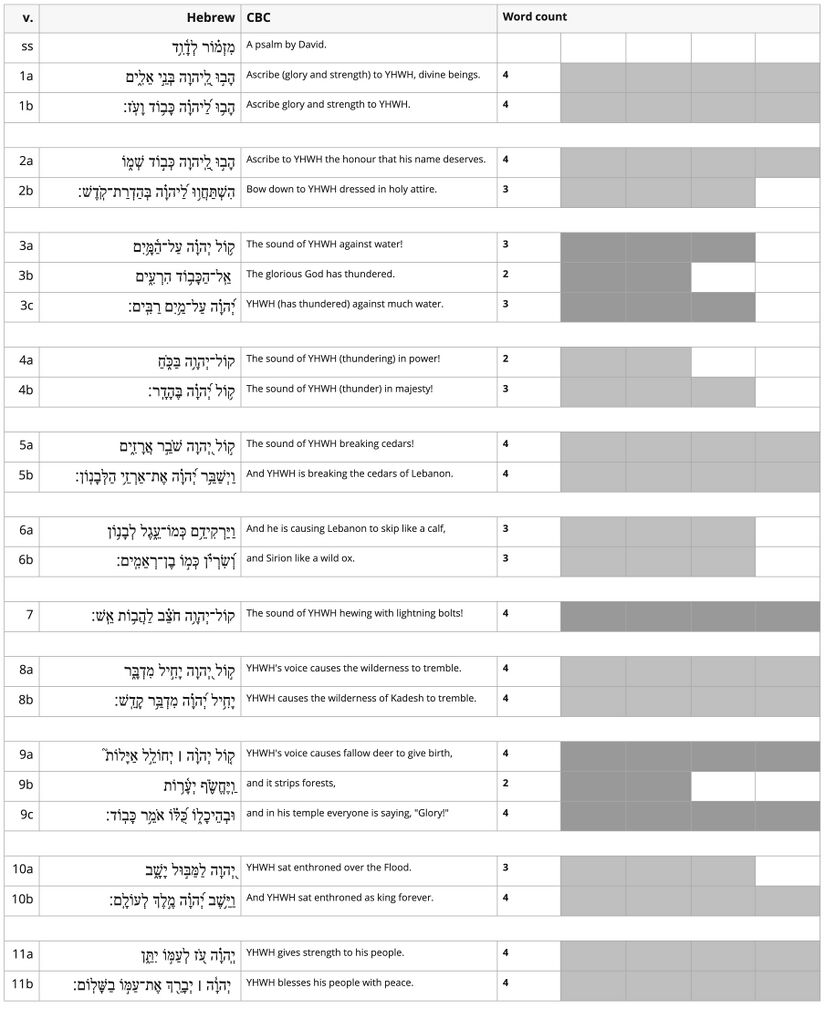

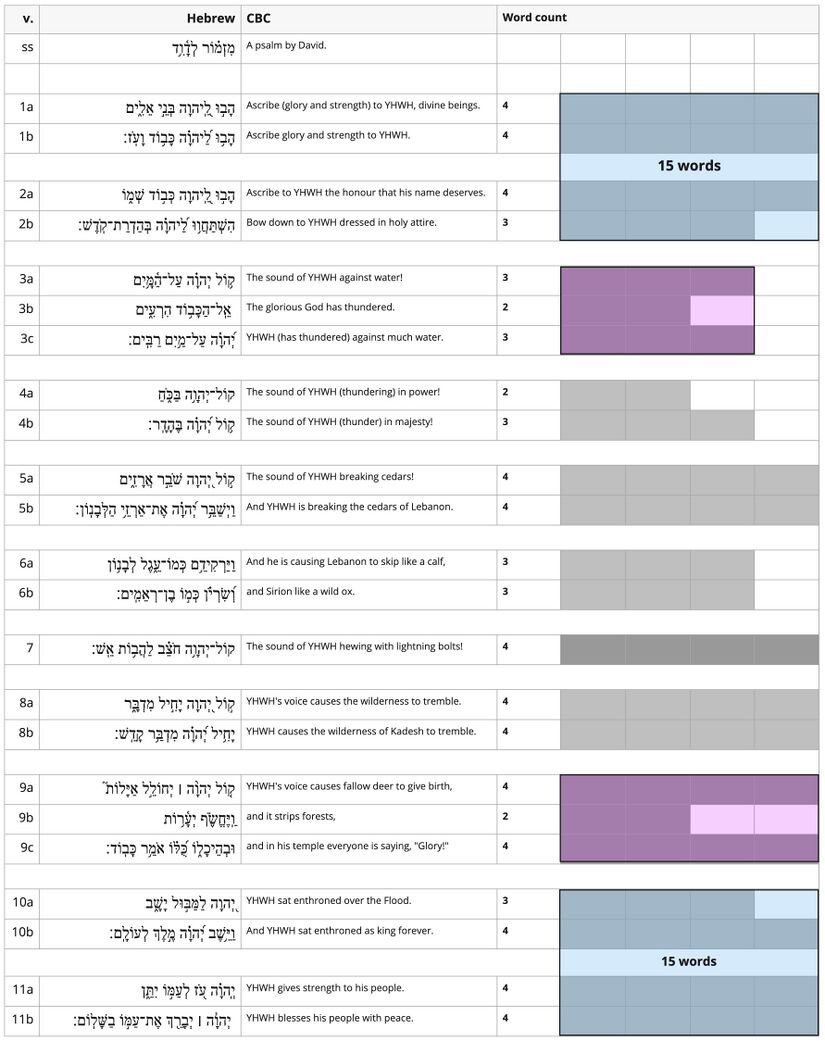

- Copy the line length template from the template board.

- Copy and paste the Hebrew text of the psalm into the "Hebrew" column, one poetic line per columnar row.

- Copy and paste the CBC into the "CBC" column, one poetic line per columnar row.

- In the far-left column ("v.") include verse/line numbers (1a, 1b, etc.; ss for superscription).

- Insert a blank row after each line grouping.

- In the first column under the heading "Word count," list the number of prosodic words in each line.

- For the remaining columns under the heading "Word count," shade the appropriate number of cells in each row, one cell per prosodic word. (Use gray #808080, shaded at 50% for line groupings that consist of two lines and 80% for line groupings that consist of more or less than two lines). Upon the completion of this step, the visual should look something like the following:

- Identify and visualize any potential patterns. For example, in Ps. 29, the first four lines have the same number of words and a similar patterning as the last four lines. Verses 3 and 9 are also similar in that they are both line triples (tricola) in which the A and C lines are the same length and the middle B line is shorter.

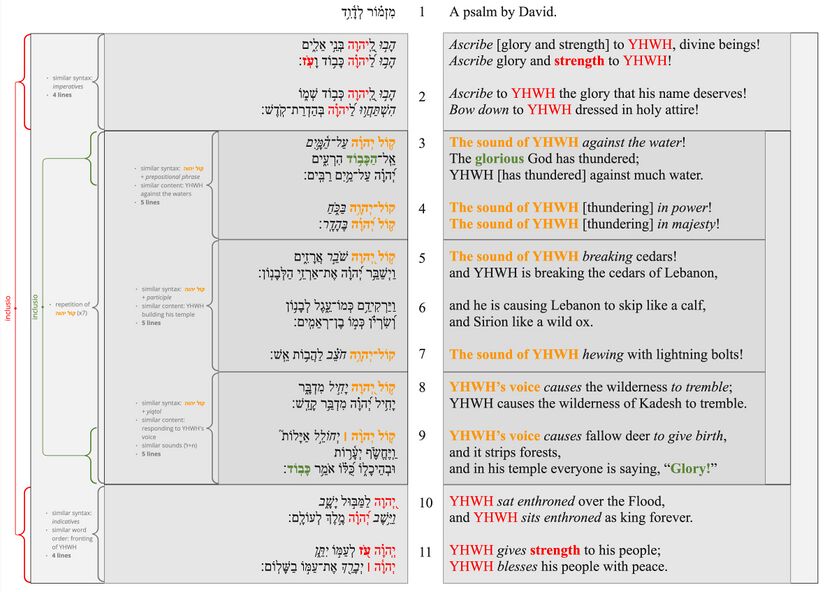

3. Poetic Structure

In several of our layers so far (e.g., participant analysis, macrosyntax, speech act analysis), we have isolated one aspect of the text (e.g., participant shifts, syntax, speech acts) and determined breaks in the text based on that one aspect. In this visual, we take into account all aspects of the text in an attempt to synthesize all previous layers of analysis and to identify the poetic structure of the poem. The structure identified at this layer will be the structure seen in the "at-a-glance" visual for the psalm.

- Copy the poetic structure template from the templates board, and paste it onto the board for your psalm.

- Copy the previously completed "Line Divisions" visual and paste it into the "Poetic Structure" template. Remove all color formatting from the text as well as all clause-end markers, blue numbers and green symbols. The only things left should be the lineated Hebrew text, the lineated CBC text, and the verse numbers in between the two texts.

- Use grey boxes to group together units of text (see visual below). Because lines are already grouped together into line groupings by spacing, there is no need to place boxes around the line groupings. Use boxes to join line groupings together into larger units of text. Depending on the size of the psalm, these larger units may then be grouped together to form even larger units, up-to and including the entire psalm. When attempting to identify larger groupings of text, it is helpful to keep in mind some of the Gestalt Principles of perception.

- According to the principle of similarity, units of text that are similar to one another tend to be grouped together. The similarity may be syntactic, lexical, semantic, phonological, prosodic or based on a combination of these or other aspects of language.

- According to the principle of closure, "stimuli tend to be grouped together if they form a closed figure."[13] Poetic inclusios often function to bind together units of text into a larger unit.

- According to the principle of good continuation, patterns tend to "perpetuate themselves in the mental process of the perceiver."[14]

- If the identification of a structural unit is based on some similarity across that unit, then use a curly braces to bind together the grey box surrounding that unit, and briefly describe in bullet points the type of similarity (see visual below). If the point of similarity is a specific and localized textual feature which may be easily coloured, then colour the text accordingly and colour the curly brace to match it (see visual below). Do the same with inclusios and other structural devices based on the principle of symmetry (similar beginnings, similar endings, chiasms, etc) (see visual below).

- [ADDED] As with other visuals, include a "Notes" box below your visual with a brief summary of the structure you captured, as well as any additional structural observations you were not able to include in your visual for the sake of clarity and simplicity. Be sure to take this opportunity to interact with secondary literature on the structure of this psalm (e.g., Fokkelman, van der Lugt, and others as available for this psalm), noting where you differ from their analyses, and why.

The Psalm 29 visual shows the following:

The Psalm 29 visual shows the following:

- The psalm is framed by an inclusio; it begins and ends with four-line unit containing the key term "strength" (עז) and the four-fold mention of YHWH's name.

- vv. 1-2 are bound together by similar syntax (imperatives).

- vv. 3-9 are bound together by the sevenfold repetition of the phrase קול יהוה. This large unit is also framed by an inclusio; it begins and ends with a tricolon that contains the word "glory".

- Within the unit of vv. 3-9, there are three sub-units, each of which is 5 lines long.

- vv. 3-4 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by prepositional phrases) and similar content (description of YHWH's battle against the waters).

- vv. 5-7 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by participles) and similar content (description of YHWH building his temple out of cedar and stone).

- vv. 8-9 are bound together by similar syntax (קול יהוה followed by finite verbs [yiqtols]), similar sounds (ח + ל), and similar content (description of creation responding to YHWH's voice).

- The final section (vv. 10-11) corresponds to the first and is further bound together by similar syntax (indicative verbs) and word order (fronting of YHWH).

See other examples of Poetic Structure visuals at the links below

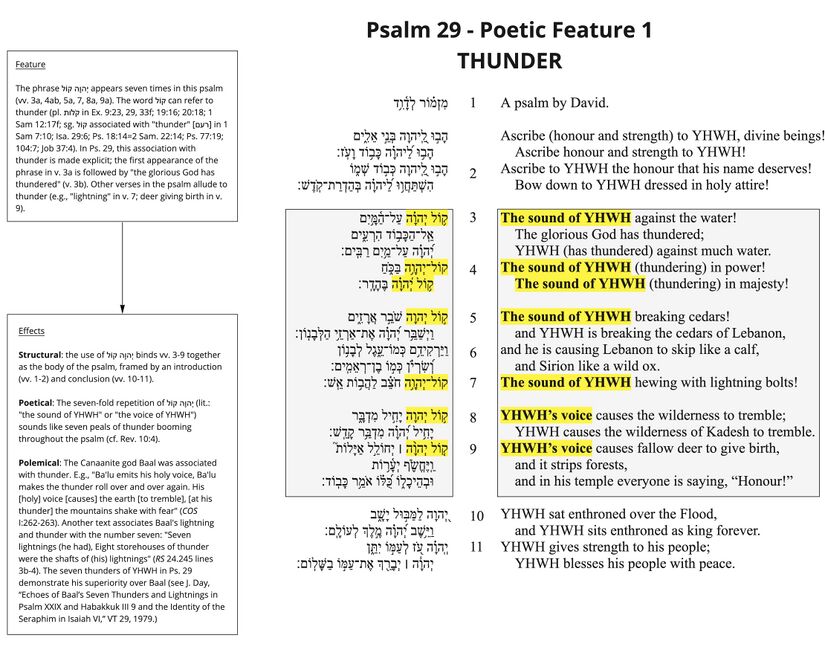

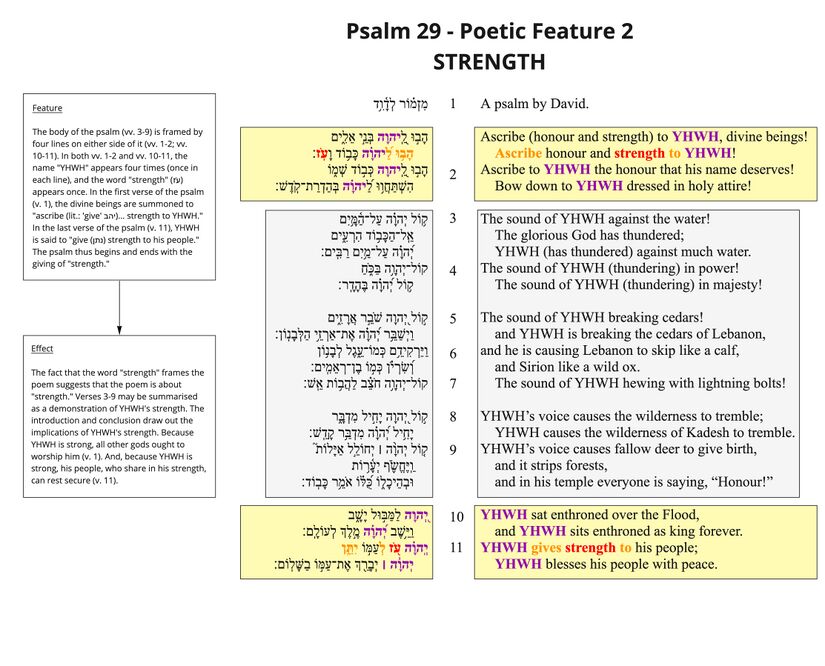

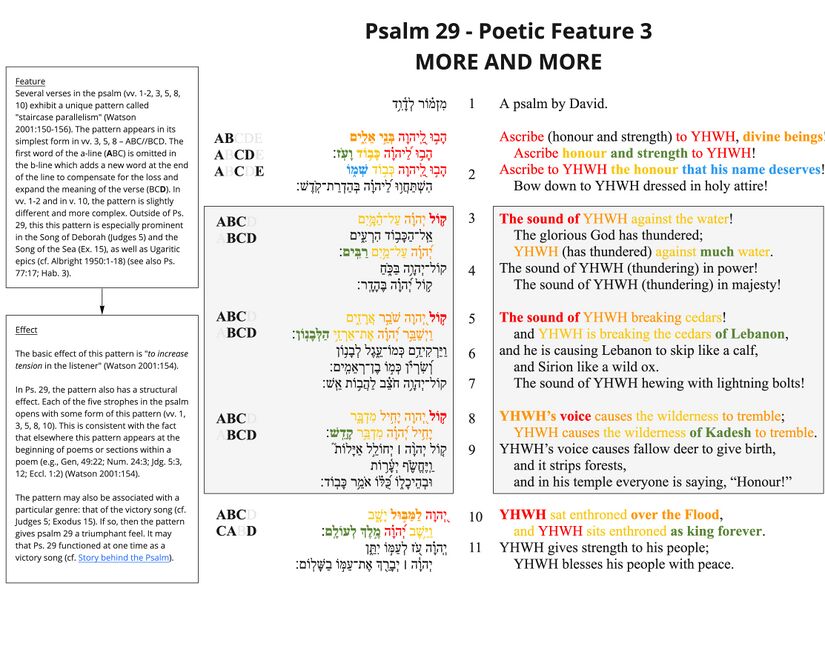

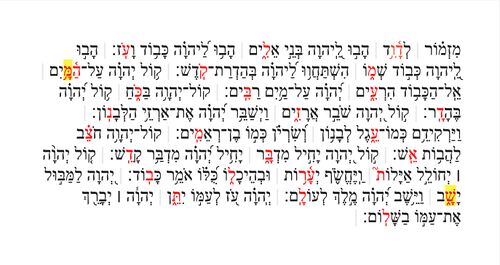

4. Poetic Features

- Copy the poetic features template from the template board and paste it onto your MIRO board.

- Copy the Hebrew-English text from the Poetic Structure visual and paste it onto the template. Delete all grey boxes and braces, and clear all special formatting of the text (e.g., bold, colour).

- Based on the Poetic Structure analysis, visually combine the lines of the text into poetic-paragraphs / strophes by deleting the space between line groupings that belong to the same paragraph (see visual below). Indent all b-lines, c-lines, and d-lines to visually indicate line-groupings within the strophes (see visual below). Indent (TAB) twice for b/c/d-lines in the Hebrew text and once for the CBC English text. At this point, the text should look something like the following:

- Copy and paste the template with the Hebrew/English text inside of it three times (one for each poetic feature).

- Now you are ready to identify the top three poetic features of the psalm. Given the unique artistry of each poem, there is no mechanical process for identifying the most significant poetic features. This identification requires thoughtful and prolonged meditation on the psalm as well as a general familiarity with Hebrew poetry and an expectation of the kinds of features Hebrew poems are likely to exhibit.[15] Nevertheless, some general guidelines for identifying the top poetic features may be given:

- Is the Psalm as a whole arranged in a pattern (e.g., acrostic, chiastic, [ADDED] parallel sections ABC-A'B'C', etc.)? If so, then this will likely qualify as a top poetic feature.

- Do noticeable and meaningful correspondences function to connect lines or strophes across the Psalm? If so, then this may qualify as a top poetic feature. The connections may be formed by repeated roots, repeated sounds, repeated semantic domains, repeated rhythmic patterns, repeated syntactic structures, (etc.) or a combination of various elements. (See e.g., Ps. 1 "No Standing"; Ps. 2 "Think Again"; Ps. 3 "Rise and Rescue; Ps. 4 "Doubles"; Ps. 6 "Repetition, Resolution, and Reversal"

- How does the author use imagery (not only figurative language [metaphors] but also concrete non-figurative images)? Do the images relate to one other in meaningful ways? (See e.g., Ps. 1 "Footsteps", Ps. 2 "Heaven and Earth and In-Between"; Ps. 4 "A New Day Dawns".

- How does the author use sound to form connections, to signal points of prominence, or to create certain moods or affects? (See e.g., Ps. 1 "Opposite direction"; Ps. 2 "Son of God"; Ps. 3 "Response to Taunts"

- Are there any points of prominence in the Psalm (i.e., place where poetic features cluster)? (See e.g., Ps. 3 "The Sound of Silencing"; "The Heights of Poetry and the Depths of Pain; Ps. 150 "Poetic Party"

- [ADDED] Does the author use text painting (i.e., use linguistic/aesthetic elements to illustrate some aspect of meaning in the poem)? (See e.g., Ps. 13 "Closer and Closer".)

- Are there any strong allusions to other portions of the OT?

- The above questions and categories by no means exhaust the kinds of poetic features in the psalms. Some of the most fascinating poetic features do not fit in any of the above categories (or they belong to multiple categories at once). See e.g., Ps. 6 "Death and Resurrection", Ps. 150 "Overflowing praise".

- [ADDED] You may have already noticed interesting features or clustering of features throughout your study of the previous layers of analysis for this psalm; however, a systematic review of the layers is likely to reveal additional ideas. Please see the [NOT SURE HOW TO LINK THIS to the appendix below] Poetic Features Appendix for additional ideas for how to structure your work for this layer.

- [ADDED] Be sure to consult the secondary literature to see what patterns others have found for this psalm (e.g., Fokkelman, van der Lugt, Auffret, Wendland, etc.).

- [ADDED] Evaluate your proposed poetic features based on these desirable characteristics:

- Poetic features should illustrate/contribute to an understanding of the overall meaning of the poem. A great example: Ps. 6 "Death and Resurrection". Helpful checks for evaluation:

- Features show connections between sentences/sections. Ask yourself: How might those connections support and/or contribute to the meaning of the psalm?

- Features cluster in order to draw attention (prominence) to a certain sentence/section of the psalm. Ask yourself: What about the highlighted portion of text might help people understand the whole poem better? Why might the author have been drawing attention to this particular part? (Also: Take a closer look at what seems to be highlighted to see if any micro-features reinforce the highlighting, cf. the first two lines of verse 4 of Psalm 13.)

- Features bring clarity to the structure of the poem (e.g., by helping highlight the boundaries of sections, or outlining a chiasm)—but only if it reinforces the meaning of the poem. [Features not contributing to meaning may be usefully added to the Poetic Structure visual and/or included in the notes for that visual.]

- Features make connections with the rest of Scripture (e.g., Ps. 14 "The World Corrupt Once Again").

- Poetic features should be distinctive to the inner logic and meaning of that particular psalm. In other words, don’t highlight a poetic device for the poetic device’s sake alone. Although a similar type of linguistic play might happen in other psalms, only mention it here if it helps bring out the meaning of the psalm.

- Usually: Poetic features involve considering most or all of the poem. For example, in Ps. 13 "Answers" certain features appear only in the first and last sections—these contrast with the middle section, where they don’t appear. A good check: Does demonstrating this poetic feature require showing and interacting with a significant portion of the text? If it only focuses on something interesting in one phrase or sentence, then it should probably be reserved for the overview video script or elsewhere.

- Poetic features should illustrate/contribute to an understanding of the overall meaning of the poem. A great example: Ps. 6 "Death and Resurrection". Helpful checks for evaluation:

- Visualise each poetic feature on MIRO using whatever visual means are most effective (e.g., bold, underline, italics, colours, highlights, shapes, etc.).

- Describe the feature in the text box labeled "Feature." This is purely descriptive and minimally interpretive. Simply describe the feature which you have visualised.

- Describe the effect(s) of the feature in the text box labeled "Effects" (see examples in the above links).

- Give the poetic feature a memorable name.

- [ADDED] Make a notes section where you include potentially poetic observations that you did not include in the top three poetic features. Someone else in the future may be able to develop these further!

Examples

Additional Resources

- Auffret, Pierre. E.g. Voyez de vos yeux. Étude structurelle de ... psaumes...

- Fokkelman, J. P. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Hermeneutics and Structural Analysis. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum, 2000.

- ———. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis. Studia semitica Neerlandica 43. Assen: Royal van Gorcum, 2003.

- Labuschagne, C.J. “Numerical Features of the Psalms, a Logotechnical Quantitative Structural Analysis.” DataverseNL, 2020.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter. Oudtestamentische studiën = Old Testament studies v. 53. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2006.

- ———. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry II, Psalms 42-89. Oudtestamentische studien = Old Testament studies v. 57. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2010.

- ———. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1. Oudtestamentische studiën = Old Testament studies v. 63. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2014.

Book Summaries:

Rubric

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Completeness |

|

| Quality of analysis |

|

| Engagement with secondary literature |

|

| Clarity of language |

|

| Formatting/Style |

|

[ADDED] Poetic Features Appendix

Poets work with the linguistic resources they have available, which means that any aspect of the text may be manipulated. For the most comprehensive review of a psalm's features (or if you're struggling to find anything useful), you can work through each of the analyses already done for the psalm. The list below provides an outline of the types of relevant features at each level of analysis. Those in bold have proven to be productive in many psalms and so are recommended as good places to start. Those in italics are not a usual part of our analysis process and have only occasionally proven to be productive, so they may be skipped unless material is needed.

For each feature you examine, check:

- Its distribution throughout the text.

- What kinds of chiastic, far parallel, or other structural patterns it might outline.

- If it seems significant: How its distribution aligns with other linguistic resources that seem significant.

- Grammar

- Repeated syntactic structures (e.g., Psalm 1, Psalm 3)

- Semantics

- Lexical Semantics

- Repetition/distribution of exact words, phrases, or word roots

- Distribution of semantic/thematically related words (or common word pairs)--note your visual for the repeated lexical domains based on SDBH, but also use your intuition; two different ways of saying "forever" in Psalm 111 proved significant.

- Distribution of rare (for right now defined as fewer than 50 occurrences) or borrowed words (cf. clumping of b/r with bar at end of Psalm 2)

- Gender of nouns

- Phrase-Level Semantics

- Distribution of prepositions (cf. beg/end use of בַּ in Psalm 13) (also Psalm 150)

- Verbal Semantics

- Distribution of verbal stems, conjugations, PGN, suffixes, etc. (e.g., the distribution of imperatives, qatals, Piel, Hiphil, or anything else appearing in the verbal semantics chart; cf. the Hiphils in the center of Psalm 13)

- Incidence of long wayyiqtol (Robar p. 180; Katie thought the Psalm 8 example might be a flashback reference to Creation)

- Incidence of paragogic nun or he (Robar p. 180)

- Lexical Semantics

- Story Behind the Psalm

- Change of scene/location (Salisbury Glossary on boundary markers; is his “change in participant” covered by change in perspective, addressee, and subject above?)

- Implicit information

- Exegetical Issues

- Note any decisions that may affect repeated roots, repeated lexical domains, repeated verbal attributes, or any of the other elements being examined.

- Discourse

- Participant Analysis

- Distribution of divine names & presence/role of enemies

- Change in speaker or addressee

- Change in subject/agent/patient (semantic roles)

- Suffixes; distribution of possessives

- Macrosyntax

- Distribution of negative markers (לֹֽ (לֹֽא אַל אֵין בַּל לְבִלְתִּי))

- Distribution of independent personal pronouns

- Distribution of vav (Psalm 13, Psalm 67)

- Distribution of other particles (אַךְ הֵן הִנֵּה גַּם כֵּן כִּי עַתָּה פֶּן לְמַעַן אִם לוּ\לוּלֵא, etc.); consider what thoughts similar particles might be connecting

- Unusual or repeated word orders (cf. Lunn p. 169, on DEF/CAN parallelism at boundary markers and peak)

- Elided information

- Speech Act Analysis

- Appearance of rhetorical questions

- Quotations and direct speech

- Participant Analysis

- Emotional Analysis

- Distribution of emotions through the text

- Poetics

- Distribution of cola (monocolons, bicolons, tricolons, tetracolons)

- Distribution of selah

- Patterns in line length

- Any features contributing to the poetic structure visual that seem to interact with the meaning of the text in a special way

- Local/mini chiasms (clause/colon level)

- Counting syllables, words, or lines (cf. the three middle words of Psalm 23 or 76)

- Distribution of sounds--though not currently in our analysis, the distribution of vowels and consonants has often proved significant (cf. Wendland and Zogbo on Ecclesiastes 1; connections in Psalm 13; Psalm 122); look for assonance, alliteration, rhyming, or significance built through sounds reserved for just one or two places in the poem (this Analysis Tool can help--choose CC from the menu to get a Consonant Chart)

References

- ↑ Wendland and Zogbo 2020:8.

- ↑ What Biblical scholars have variously referred to as stich, hemistich, colon, verset, half-line, etc. is here referred to as “line” because (1) this term has “a long-standing scholarly tradition of use within biblical studies" (Dobbs-Allsopp, 2015:22); (2) this is the term used for this phenomenon “in the discipline of Western literary criticism” (Dobbs-Allsopp, 2015:22); (3) “this is the terminology used in discussing other traditions of poetry throughout the world” (Wendland and Zogbo, 2020:22). For more on the concept of the poetic line, see the book summary of Unparalleled Poetry.

- ↑ “Line structure in a given poem emerges holistically and heterogeneously. Potentially, a myriad of features (formal, semantic, linguistic, graphic) may be involved. They combine, overlap, and sometimes even conflict with one another… Thus what is called for is a patient working back and forth between various levels and phenomena, through the poem as a whole, considering the contribution, say, of pausal forms alongside and in combination with other features” (Dobbs-Allsopp 2015:56).

- ↑ Pausal forms often mark the end of a poetic line. See E.J. Revell, “Pausal Forms and the Structure of Biblical Hebrew Poetry,” Vetus Testamentum 31, no. 2 (1981): 186–199.

- ↑ The following analysis of the accents is based on Sanders and de Hoop, forthcoming §1.4.2. According to Sanders and de Hoop, the basic purpose of the accents is to guide the recitation of the text (see Sanders and de Hoop, "The System of Masoretic Accentuation: Some Introductory Issues") and not necessarily to mark poetic lines. Thus, the relationship between the accents and poetic line division is indirect. See the discussion on the Pericope website.

- ↑ When atnaḥ follows 'ole weyored, it is less likely to correspond with the end of a line.

- ↑ This accent is also known as "defective revia mugraš" or "revia mugraš without gereš".

- ↑ "We define a precursor as a disjunctive accent that is subordinate to the following disjunctive accent and subdivides the domain of that following accent" (Sanders and de Hoop, forthcoming §1.3)

- ↑ Krohn defines prosodic words as "i) unbound orthographic words that have at least one full syllable (CV, where V is not a shewa), or ii) orthographic words joined together by cliticization (Krohn 2021:103).

- ↑ Cf. Krohn 2021:103. According to Geller, “lines contain from two to six stresses, the great majority having three to five” (NPEPP, 1998: 510). Hrushovski suggests a narrower range of two to four stresses (“Prosody, Hebrew,” 1961).

- ↑ Emmylou Grosser notes in her analysis of Judges 5 and the Balaam Oracles of Num. 23-24 that symmetrically-arranged line pairs tend to have “either equal stresses, or stresses unequal by one with balance of syllables deviating by no more than one” (Grosser: “Symmetry” 2021). Given this tendency toward rhythmic balance, Geller concludes that “passages with such symmetry form an expectation in the reader’s mind that after a certain number of words a caesura or line break will occur… The unit so delimited is the line. So firm is the perceptual base that long clauses tend to be analyzed as two enjambed lines” (Geller, "Hebrew Prosody", NPEPP, 509-510).

- ↑ Psalms begin on Folio 632.

- ↑ Grosser Unparalleled Poetry 2022:247.

- ↑ Grosser Unparalleled Poetry 2022:226.

- ↑ For the latter, see e.g., Wilfred Watson, Classical Hebrew Poetry: A Guide to its Techniques (Sheffield Academic Press: Sheffield), 2001; Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry; Adele Berlin, The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism